Wood Ducks: North America’s Tree-Nesting, Wild Beauties

Few birds capture the eye quite like the Wood Duck. With its dazzling plumage, graceful shape, and preference for wooded waterways, this native North American species is often considered one of the most beautiful ducks in the world. But there’s much more to them than their looks.

Unlike domestic breeds like Pekins or Khaki Campbells, Wood Ducks are wild animals. They nest in tree cavities, migrate with the seasons, and require special permits to keep in captivity. As pet duck keepers, we often admire them from afar—or, if we’re lucky, from the edge of our pond.

In this post, we’ll explore everything you need to know about Wood Ducks: their natural behaviors, nesting and migration habits, what they eat, how they differ from domestic breeds, and the strict legal guidelines around keeping them. Whether you’re simply fascinated by their wild beauty or curious about what it takes to care for one legally, this guide has you covered.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

General Traits Table

| Trait | Wood Duck |

|---|---|

| Species | Aix sponsa (not Anas platyrhynchos) |

| Origin | North America |

| Status | Wild species (permit required) |

| Size | Medium-sized |

| Weight | 454–862 grams (16.0–30.4 oz). |

| Lifespan | 3–4 years in the wild (longer in captivity) |

| Temperament | Shy, alert, quick to flush |

| Flight Ability | Excellent flyers |

| Egg Production | 6–15 eggs per clutch (wild) |

| Broodiness | Yes |

History and Background of Wood Ducks

The Wood Duck (Aix sponsa) is one of the most distinctive and stunning duck species native to North America. Unlike domestic ducks, which descend from the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) or Muscovy (Cairina moschata), Wood Ducks are a separate species altogether—belonging to the perching duck group. Their name comes from their preferred habitat: wooded swamps, forested wetlands, and rivers with overhanging trees, where they’re often seen perched on branches or nesting in hollow trunks.

Known for its iridescent plumage, crest, and red eyes, the drake’s bold coloring has earned it nicknames like “summer duck” and “bridal duck.” But this bird’s story goes far beyond its good looks.

The Wood Duck was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of Systema Naturae, where he classified it under the name Anas sponsa. Linnaeus based his description on the “summer duck” from Carolina, as illustrated by the English naturalist Mark Catesby in The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1729–1731). While Linnaeus initially gave its range as all of North America, later taxonomic work restricted the type locality to Carolina, in reference to Catesby’s work.

In 1828, German naturalist Friedrich Boie reclassified the species into the genus Aix, grouping it with its Asian cousin, the Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata). The genus name Aix comes from Ancient Greek, referencing an unidentified diving bird mentioned by Aristotle. The species name sponsa is Latin for “bride,” likely a nod to the male Wood Duck’s striking, ornate plumage that resembles a groom in formal dress.

The Wood Duck is monotypic, meaning it has no recognized subspecies. While widely distributed, all Wood Ducks belong to the same species and exhibit remarkably consistent traits across their range.

By George Schmiesing via Adobe Stock.

Conservation-wise, this species represents a true success story. By the early 1900s, overhunting and habitat destruction had pushed Wood Ducks to the brink of extinction. But with the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and widespread public involvement in nest box programs, the species made a dramatic comeback. Today, Wood Ducks are commonly seen in forested wetlands, backyards with ponds, and even urban green spaces—provided there’s enough cover and water.

Although they are thriving in the wild, it is illegal to capture or keep a Wood Duck without proper permits. They remain protected under federal law, and any captive care must meet stringent wildlife regulations.

Wood Duck Appearance

Wood Ducks have one of the most recognizable profiles among North American waterfowl. Their body shape is unique, characterized by a boxy, crested head, a slender neck, and a long, broad tail. Even in flight, they stand out by holding their head high, sometimes with a noticeable bob. Their silhouette is long and lean, with short, rounded wings and a thick, squared-off tail that helps with maneuverability in tight forested spaces.

Size and Measurements

Wood Ducks are medium-sized ducks:

- Length: 18.5–21.3 inches (47–54 cm)

- Weight: 16.0–30.4 ounces (454–862 g)

- Wingspan: 26.0–28.7 inches (66–73 cm)

Male (Drake)

In good lighting, the drake is absolutely stunning. He displays an iridescent green and purple crest, sharply defined white stripes across the face and neck, a deep chestnut breast, and warm buffy flanks. His red eyes and bright bill add even more contrast. In dim or harsh light, his dramatic colors can appear more muted, seeming dark overall with paler edges. During eclipse plumage (late summer), the male molts into a more subdued look—losing his side stripes and rich flank coloring—but he keeps his red eye and colored bill, which makes him easier to identify even outside the breeding season.

Female (Hen)

The female Wood Duck is more understated but still elegant. She wears soft gray-brown feathers with a white-speckled breast and a distinctive white teardrop-shaped eye ring. Her plumage offers excellent camouflage, especially when nesting.

Ducklings and Juveniles

Wood Duck ducklings are downy with dark heads, pale cheeks, and bold white eye stripes. Juveniles resemble adult females but tend to have duller coloring and less defined markings until their first full molt.

Wood Ducks don’t just stand out for their plumage—they’re built for life in wooded wetlands. Their strong claws help them perch on branches, and their tail-heavy bodies and short wings are well-suited for quick takeoffs and agile flight through trees.

Egg Production

As a wild species, Wood Ducks are seasonal layers that follow natural environmental cues, especially day length and temperature. Unlike domestic breeds that may lay regularly year-round, Wood Ducks typically produce one to two clutches per year during the spring and early summer.

Clutch Size and Laying Habits

- A typical clutch contains 6 to 15 eggs, though nest parasitism (multiple females laying in the same nest) can lead to clutches with over 20 eggs.

- The eggs are usually creamy white to light tan in color, with a smooth shell and elliptical shape.

- Females lay one egg per day until the clutch is complete, and then begin full-time incubation.

Incubation and Hatching

- The incubation period lasts 28 to 30 days, and the female does all the brooding herself.

- During this time, she may only leave briefly once or twice a day to feed and bathe before returning to the nest.

- Once the ducklings hatch, they spend only about 24 hours in the nest before making their iconic leap to the ground or water below.

Reproduction in Captivity

Captive-bred Wood Ducks with proper housing and minimal stress may lay and hatch eggs reliably in the spring, especially when provided with elevated nest boxes that mimic natural tree cavities. Some breeders provide multiple nest boxes per pair to reduce competition and allow hens to choose their preferred site.

By Gordon via Adobe Stock.

While their egg production isn’t comparable to that of high-laying domestic breeds like Khaki Campbells or Golden 300s, Wood Ducks are highly devoted mothers and often raise large, healthy broods—provided they have the right setup and minimal disturbance.

It’s also worth noting that collecting Wood Duck eggs or disturbing wild nests without a permit is illegal under federal law. If you’re hoping to observe or raise Wood Ducks, it’s essential to work with a licensed breeder or conservation program.

Natural Behavior and Wild Habitat

Wood Ducks are specially adapted to life in wooded wetlands, making them quite different from most dabbling ducks. They prefer quiet, forested areas near freshwater sources such as swamps, ponds, creeks, and slow-moving rivers. You’ll often spot them where trees meet water, particularly in areas with overhanging branches or abundant aquatic vegetation.

Unlike domestic duck breeds, Wood Ducks are expert climbers and agile flyers. Thanks to their strong claws, they can perch in trees, grip bark, and even navigate narrow branches. Their short, broad wings allow for quick, maneuverable flight, essential for darting through dense woodland. When startled, they often burst into flight with a loud, high-pitched oo-eek! call and a flash of color.

These ducks are shy and alert, often flushing at the slightest disturbance. They tend to forage along the water’s edge and dabble in shallow areas for food. Their natural diet includes:

- Aquatic invertebrates (insects, snails, larvae)

- Seeds and aquatic plants

- Berries and small fruits

- Acorns and other tree nuts (especially in fall and winter)

Wood Ducks are most active during the early morning and late evening hours, often roosting in trees or secluded areas of wetlands during the day. While you may see them in pairs or small family groups, they’re less social than domestic ducks and typically don’t form large flocks outside of migration.

Because of their dependence on trees for both shelter and nesting, habitat conservation is especially important for Wood Ducks. Wetland destruction, removal of mature trees, and pollution can quickly reduce the areas where they can safely live and breed.

If you’re lucky enough to live near a wooded pond, you might spot a pair in spring or fall—especially if you’ve put up a nest box. But don’t expect them to hang around like domestic ducks; they tend to keep their distance and follow the rhythms of the wild.

Migration and Breeding

Wood Ducks are partial migrants, with many northern populations traveling south each fall while southern birds often remain year-round. Their migratory routes generally follow the Mississippi and Atlantic flyways, with birds from the northern U.S. and Canada wintering as far south as Florida, the Gulf Coast, and even parts of Mexico.

In North Texas, we’re lucky to see Wood Ducks throughout the year. While some are just passing through during migration, others may stay to nest if the habitat is right—especially near wooded ponds or wetlands with natural cavities or nest boxes.

By Jim Cumming via Adobe Stock.

Breeding Season and Nesting Behavior

Wood Ducks begin nesting in early spring, often as early as March in the southern U.S., and slightly later in the north. Unlike most ducks, Wood Ducks are cavity nesters. They search for hollow trees near water—often created by woodpeckers or natural decay—typically 2 to 60 feet above ground or water level. Because suitable cavities can be hard to find, they readily accept artificial nest boxes, which have played a major role in their population recovery.

The female usually lays between 6 and 15 creamy white to tan eggs in a clutch. She may even lay eggs in another female’s nest—a behavior called brood parasitism, which can result in very large clutches of over 20 eggs.

Incubation lasts around 28 to 30 days, during which the mother does all the brooding. The male usually stays nearby for a while but may leave before the ducklings hatch.

By onewildlifer via Adobe Stock.

The Famous Leap

One of the most incredible things about Wood Ducks is what happens after hatching. Within 24 hours, the ducklings—still covered in down—climb to the nest entrance and leap from the cavity to the ground or water below. This jump can be over 30 feet, but thanks to their light bodies and soft down, they usually land unharmed and immediately follow their mother to water.

Unlike domestic ducklings, Wood Duck babies are precocial, meaning they are mobile and able to feed themselves from the very beginning. The mother leads them to foraging spots and protects them, but they quickly learn to find insects, seeds, and small aquatic prey on their own.

The ducklings fledge in about 8 to 10 weeks, developing their flight feathers and eventually becoming independent.

Housing and Diet in Captivity

Keeping Wood Ducks in captivity is a serious commitment—not just in terms of care, but also in meeting legal and ethical responsibilities. Because they are a protected wild species, you must obtain a federal permit through the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (and possibly a state-level permit as well) before housing them. These permits are typically only granted for specific purposes such as conservation breeding, education, or wildlife rehabilitation.

Housing Requirements

Wood Ducks need a secure, naturalistic enclosure that supports their flight instincts, perching behavior, and strong need for privacy. Unlike domestic ducks, they won’t thrive in open pens or small backyard runs.

A suitable captive habitat should include:

- A fully enclosed aviary with overhead netting or solid roofing to prevent escape

- Plenty of vertical space for flying short distances and perching

- Natural cover such as shrubs, branches, and tall grasses to reduce stress

- Elevated nest boxes mounted 4–10 feet off the ground, mimicking their tree cavity nesting sites

- A clean water source, like a small pond or deep tub, for bathing and foraging

Dry, draft-free shelters may also be provided in colder climates, but these should still allow access to fresh air and light. The key to success is mimicking a quiet, semi-wild woodland environment that minimizes stress and encourages natural behaviors.

By Daniel Teetor via Adobe Stock.

Diet in Captivity

In the wild, Wood Ducks forage on a mix of plant matter and protein-rich foods like aquatic insects and larvae. In captivity, their diet should reflect this balance.

A proper feeding plan includes:

- Game bird or waterfowl pellets designed for wild ducks (Mazuri, Purina, or specialty feeds)

- Greens and aquatic plants like duckweed, romaine, and chopped dandelion

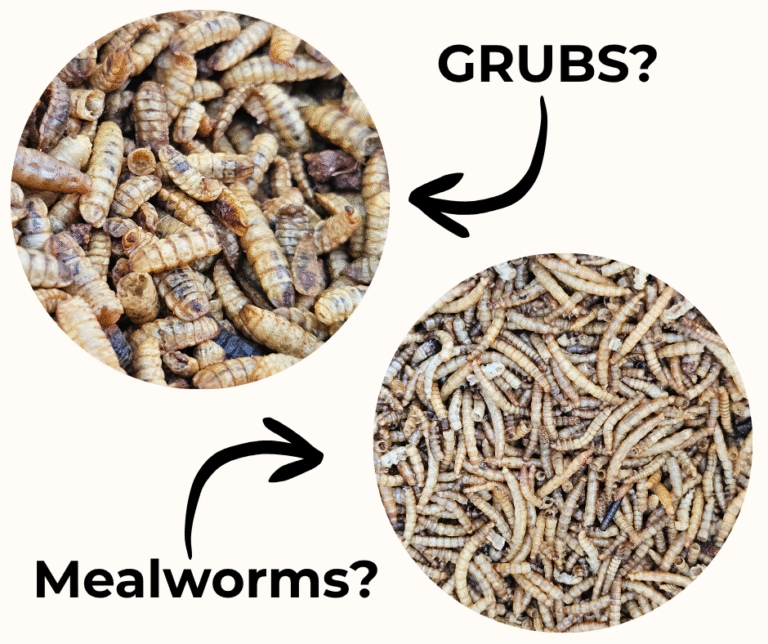

- Insects such as mealworms, waxworms, or black soldier fly larvae as protein sources

- Occasional grains and seeds, like oats, millet, and cracked corn

- Access to clean water deep enough to dunk their entire head while eating

Because Wood Ducks are less prone to overfeeding than domestic breeds, they can be fed more naturally—scattering feed or offering it in water encourages foraging behaviors and reduces boredom.

It’s also essential to monitor their health closely. Stress, poor diet, or lack of enrichment can lead to feather damage, suppressed immune response, or digestive issues in this sensitive species.

Temperament and Behavior in Captivity

Wood Ducks are fundamentally wild birds, and even when raised in captivity, they retain much of their natural instinct. Unlike domestic ducks bred for generations to be calm and people-friendly, Wood Ducks are shy, alert, and easily spooked. They are quick to take flight when startled, and they often prefer to perch in elevated areas or hide in dense cover rather than interact with humans.

If you raise them from hatchlings, they may become somewhat more tolerant of your presence, especially if handled gently and consistently. However, even imprinted individuals rarely reach the same level of friendliness or dependence seen in breeds like Pekins or Runners. Most Wood Ducks prefer minimal human interaction and require environments that mimic their natural habitat to thrive.

Because of their small size and strong flying ability, containment is also a challenge. Wood Ducks are excellent fliers and will take off at the first chance if given the opportunity. For this reason, anyone keeping them in captivity must provide a fully enclosed aviary—not just to prevent escape but also to protect these more delicate birds from stress and predators.

Their shy temperament and high energy make them less suitable for traditional backyard duck setups. They are best kept by experienced waterfowl keepers who are committed to providing specialized housing and meeting the legal requirements for keeping wild birds.

Special Considerations for Pet Owners

While it’s easy to admire the beauty and unique behavior of Wood Ducks, it’s important to remember: they are wild birds, not domestic pets. Keeping one isn’t as simple as adopting a Mallard or Runner duck. In fact, owning a Wood Duck without the proper federal and (in many states) state permits is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Legal Requirements

To keep a Wood Duck legally in the U.S., you must:

- Obtain a Federal Migratory Bird Permit through the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

- In some states, secure additional state wildlife permits

- Meet strict standards for aviary design, recordkeeping, and care

- Use banding or marking to identify captive-bred individuals (wild-caught birds cannot be kept)

These permits are usually issued only to individuals or facilities with experience in wildlife care, conservation, or education. If someone is offering Wood Ducks for sale without paperwork or permit documentation, it’s a red flag—and most likely illegal.

By Michael via Adobe Stock.

Behavioral Considerations

Even when raised from hatchlings, Wood Ducks remain instinctually wild. They’re not suited for life indoors, diapering, cuddling, or free-ranging. Attempting to raise a Wood Duck like a domestic duck can result in chronic stress, injury, or escape.

They also:

- Spook easily and may injure themselves trying to flee

- Require flight space and perches to maintain physical and mental health

- Do poorly in loud or busy environments

If your goal is to have a social, hands-on pet duck, a domestic breed is a far better choice. However, if you’re passionate about native wildlife, have the right permits, and are committed to providing a naturalistic, secure aviary, then Wood Ducks can be incredibly rewarding to observe and care for.

From Our Backyard: A Familiar Wild Visitor

Every summer, we’re lucky to have a very special visitor—a gorgeous male Wood Duck (“Woody”) who returns to the pond behind our property year after year. While he’s definitely a wild duck, he seems to feel at home near us and our flock. He’ll often stroll into our backyard or perch casually on the fence of our duck run, quietly observing the activity.

Over time, he’s grown more comfortable with our presence, and he even appears to have taken a liking to one of our girls—Schnatterinchen. We joke that he has a bit of a crush on her. Of course, she’s a domestic duck and much bigger than him, but he doesn’t seem to mind one bit. He’ll stand near her like he’s part of the flock, although she’s never quite sure what to make of him.

Last year, he stayed nearby during his eclipse molt, when drakes temporarily lose their vibrant plumage and look more like females. Watching him gradually transition back into his brilliant fall colors was such a gift—it’s a reminder of how much beauty there is in the quiet cycles of nature when we take time to notice.

Even though he’s wild, his visits feel deeply personal. And while we’d never dream of trying to tame or keep him, his presence is a gentle reminder of the bond we can form with the wild world—simply by making space, staying still, and observing with care.

FAQ: Wood Ducks

Can I keep a Wood Duck as a pet?

Only with a federal permit. Wood Ducks are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. It’s illegal to keep them without authorization, and permits are typically only granted for conservation, breeding, or educational purposes—not as household pets.

Are Wood Ducks the same as Mallards?

No. While both are dabbling ducks, they are different species. Wood Ducks (Aix sponsa) are smaller, more colorful, and adapted to forested wetlands and tree nesting. Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) are the ancestors of most domestic duck breeds and have very different behaviors.

Do Wood Ducks lay eggs like domestic ducks?

Yes, but only seasonally. Wild females typically lay 6–15 eggs per clutch, usually in spring. They don’t lay regularly like domestic ducks bred for egg production.

Can I attract Wood Ducks to my backyard pond?

Yes—if you live in their range and have the right habitat. Install a nest box on a tree or post near water (about 4–10 feet high) and maintain a quiet, wooded environment. Avoid chemicals in your pond and provide native vegetation.

What do Wood Duck ducklings eat?

In the wild, they feed themselves from day one—eating small aquatic insects, larvae, seeds, and plant matter. Captive-raised ducklings should be given a game bird starter feed with added protein (no medicated chick starter) and access to clean water at all times.

How long do Wood Ducks live?

In the wild, they typically live 3 to 4 years, though some individuals can live longer with good conditions. In captivity, with proper care, they may live up to 10 years or more.

Can Wood Ducks fly?

Yes—extremely well. Wood Ducks are strong, agile fliers and require fully enclosed aviaries in captivity to prevent escape and injury. Never clip their wings if you’re raising them under permit; flight is essential for their physical and mental health.

Are Wood Ducks endangered?

No. They were once in serious decline but are now considered a conservation success story. Thanks to legal protections and nest box programs, their populations are currently stable.

What’s the difference between a male and female Wood Duck?

Males (drakes) are brightly colored with iridescent green heads, white facial markings, and chestnut breasts. Females are gray-brown with a white teardrop-shaped eye ring, offering excellent camouflage.

Final Thoughts

Wood Ducks are truly one of nature’s most breathtaking birds—graceful in flight, stunning in plumage, and full of fascinating behaviors that set them apart from domestic duck breeds. From their tree-nesting habits to the fearless leaps of their newly hatched ducklings, every part of their life cycle reflects their wild origins and deep connection to forested wetlands.

For pet duck owners, it’s important to remember that Wood Ducks are not backyard companions. They are wild animals protected by law, and keeping them requires a federal permit, specialized care, and a naturalistic environment that meets their physical and behavioral needs.

That said, there’s still so much joy to be found in simply observing these birds in the wild—or supporting their conservation by installing nest boxes near wooded ponds. Creating safe habitats for them on your property, if you live within their range, is one of the most rewarding ways to contribute to their well-being.

Whether you admire them from afar or care for them under licensed conditions, Wood Ducks remind us of how deeply beautiful and complex our native waterfowl can be.

Other Breeds

- Cayuga Ducks: The Beautiful Black Duck Breed

- Ancona Duck – A Rare Duck Breed

- Muscovy Ducks: The Gentle Giants of the Duck World

- Welsh Harlequin Duck – Friendly, Hardy, and Stunningly Unique

- Khaki Campbell: The Champion Egg Layer That Can (Almost) Fly

- Crested Ducks: Pets with a Genetic Defect

- Indian Runner Ducks: The Upright, Active, and Entertaining Breed

- Pekin Ducks: The Classic Backyard Companion

- Silver Appleyard Ducks: The Beautiful Heavyweight Champions of Egg Production

- Swedish Ducks: Calm, Hardy, and Strikingly Beautiful

- Call Ducks: Tiny Ducks with Big Personalities