The Science of Imprinting: Why Some Ducks Bond So Strongly to Humans

Last updated: February 28th, 2026

If you have ever had a duck follow you from room to room, fall asleep at your feet, or call out the moment you disappear from view, you have witnessed imprinting firsthand. In my own home, I see this daily with my ducks, Muffin and Krümel. Because they are imprinted on me, our bond goes beyond simple pet ownership. To them, I am the anchor of their social world.

While these moments feel deeply personal and emotional, this kind of attachment is rooted in biology and survival driven learning. This process is especially common in pet ducks that were incubator hatched, rescued, or raised closely with humans. In those early hours after hatching, a duckling’s brain is actively searching for something to define as family. Whoever provides warmth, food, movement, and reassurance during that short window becomes the center of their world.

Understanding the science behind imprinting explains why some ducks bond so intensely to humans and why those bonds do not fade with age. It also helps us make thoughtful decisions as duck parents. Imprinting is not just about affection. It influences behavior, emotional well-being, flock dynamics, and long term care needs. For Muffin and Krümel, imprinting means they look to me for security and social cues. This provides a unique look at how biological scripts play out in a domestic setting. By looking at imprinting through both a scientific and practical lens, we can better support our ducks while honoring the trust they place in us so early in life.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

Part of the Community & Behavior Hub, Exploring the social complexity and psychological needs of domestic ducks.

What Is Imprinting?

Imprinting is a specialized form of learning that occurs during a narrow and time-limited window early in a bird’s development. In ducks, this sensitive period usually begins shortly after hatching and lasts for roughly one to two days. During this time, the duckling’s brain is biologically primed to identify a caregiver and establish a lasting attachment.

Unlike learned behaviors that develop gradually through repetition, imprinting happens rapidly and with remarkable permanence. Once the attachment is formed, it becomes the duck’s primary reference point for safety, social interaction, and environmental navigation. This is why imprinting is often described as irreversible under normal circumstances.

From a scientific perspective, imprinting is classified as a type of filial attachment. Its primary function is survival. A duckling that quickly recognizes and follows a caregiver is far more likely to remain warm, access food, and avoid threats. Natural selection strongly favors individuals that form this attachment efficiently and reliably.

Neurologically, imprinting coincides with a period of heightened brain plasticity. During this stage, specific regions involved in sensory processing and memory formation are especially responsive to visual and auditory stimuli. The duckling’s brain rapidly encodes the appearance, movement, and sounds of the caregiver and links them to feelings of safety and comfort.

Importantly, imprinting is not based on species recognition in the way many people assume. The duckling does not inherently know what a duck parent looks like. Instead, it bonds with the first suitable moving and responsive figure it encounters during the sensitive period. In a natural setting, this is almost always the mother duck. In human-managed settings, that figure may be a person.

Because imprinting occurs so early and shapes foundational social understanding, its effects persist into adulthood. An imprinted duck does not simply remember the caregiver. The caregiver becomes part of the duck’s core social identity. This is why imprinting influences long-term behavior, attachment patterns, and social preferences long after the duckling phase has passed.

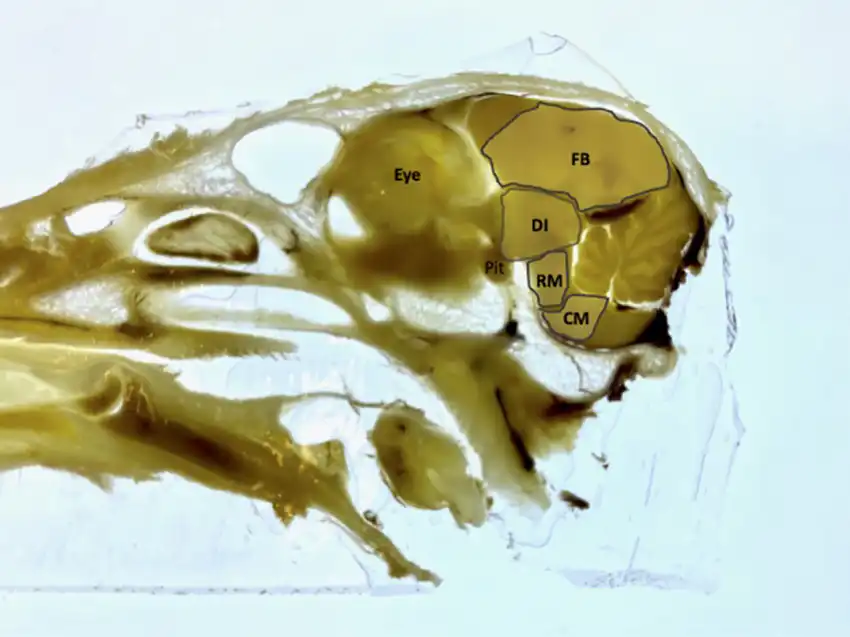

What Happens in the Duck Brain?

Imprinting is not simply an emotional response. It is a tightly coordinated neurological process that unfolds during a brief window of early brain development. During this period, the duckling’s brain is undergoing rapid growth, with neural circuits forming and reorganizing at an exceptional rate. This heightened plasticity allows the brain to quickly link sensory information with meaning.

Research in avian neurobiology shows that imprinting involves brain regions responsible for learning, memory, and sensory integration. Visual input plays a particularly important role, since ducklings rely heavily on movement and shape to identify a caregiver. Auditory cues such as soft vocalizations or consistent sounds also become strongly associated with safety and reassurance.

At the cellular level, repeated exposure to the same caregiver strengthens specific neural pathways through synaptic reinforcement. Neurons that fire together repeatedly form more stable connections, effectively locking in recognition of that individual. Once these pathways stabilize, the brain no longer treats the caregiver as just another stimulus. Instead, it categorizes that individual as a primary attachment figure.

Hormonal signaling further reinforces this process. Early bonding experiences are linked to neurochemicals involved in stress regulation and social attachment. When the duckling is near the imprinted figure, stress responses are reduced and exploratory behavior increases. When separated, stress signals rise, triggering distress vocalizations and searching behaviors. These responses are adaptive and designed to keep the duckling close to its caregiver.

Crucially, the sensitive period for imprinting closes as the brain matures. As neural plasticity decreases, the brain becomes less able to form new primary attachment templates. This is why imprinting does not easily transfer later in life and why early experiences carry such lasting weight.

The result is a stable neural framework that defines how the duck perceives social safety. The imprinted individual is not just familiar. They are neurologically encoded as a source of protection and social orientation. This brain level wiring explains why imprinting remains powerful long after the duckling stage and why its effects can be seen throughout the duck’s lifetime.

Why Humans Can Become the “Parent”

From a duckling’s perspective, the identity of a parent is defined by function rather than species. The brain is not asking whether the caregiver has feathers. It is asking who provides warmth, protection, food, and consistency during a very specific developmental window.

When ducklings hatch naturally, these cues come from the mother duck. Her movement, vocalizations, body heat, and constant presence provide a complete sensory package that the duckling’s brain is primed to recognize as safety. In human-managed environments, those same cues may instead come from a person.

Incubator hatching, rescue situations, or early separation from the mother create conditions where humans fill that role by default. If a human is the first responsive figure the duckling sees, hears, and interacts with, the duckling’s brain may encode that human as its primary caregiver. This process happens automatically and without intention on the duckling’s part.

Human behavior often amplifies this effect. Gentle handling, feeding, brooder maintenance, and frequent interaction provide repeated sensory input that reinforces recognition. Even subtle cues such as a familiar voice, footsteps, or routine movements can become deeply associated with comfort and security.

Limited exposure to other ducks during the sensitive period further increases the likelihood of human imprinting. Without alternative social models, the duckling has no competing template for what a caregiver should be. The brain commits fully to the most reliable and consistent figure available.

It is important to understand that imprinting on humans is not a sign of confusion or abnormal development. It is a predictable outcome of a flexible and highly adaptive survival system. The duckling is doing exactly what its biology instructs it to do.

Once established, this attachment does not distinguish between human and duck relationships. The imprinted human occupies the same neurological category as a parent would in a natural setting. This explains why imprinted ducks often seek proximity, show distress during separation, and form bonds that feel remarkably deep and personal.

Recognizing this process helps shift the conversation away from blame or novelty and toward responsibility. When humans become the parent in a duck’s brain, they also take on a long-term role in meeting that duck’s social and emotional needs.

Signs Your Duck Is Imprinted on You

Imprinting shows up through a consistent pattern of behaviors that reflect attachment rather than simple friendliness. These behaviors tend to be stable over time and are most noticeable when you compare the duck’s interactions with you to how they behave around other people or other ducks.

One of the most common signs is persistent following. An imprinted duck often chooses to stay close to their person, walking behind them, positioning themselves nearby during routine tasks, or relocating when the person moves to a new space. This behavior is not curiosity alone. It reflects the duck’s internal drive to remain near its primary attachment figure.

Vocalization patterns can also be telling. Imprinted ducks frequently vocalize when they lose visual contact with their person. These calls are often more urgent or specific than general flock noises and may stop immediately once contact is restored. Many duck parents learn to recognize these calls as distinct from everyday quacking.

Preference for human company over duck company is another key indicator. While many imprinted ducks can coexist peacefully with a flock, they may consistently choose human interaction when given the option. This can include approaching you first, lingering near you even when other ducks are nearby, or showing less interest in normal flock activities when you are present.

Physical proximity seeking is common as well. An imprinted duck may settle near your feet, lean against your legs, or choose resting spots close to where you are sitting. Some seek gentle contact and appear visibly calmer when close to their person. This proximity provides neurological reassurance similar to what a duckling would experience near a parent.

Separation responses often make imprinting unmistakable. When an imprinted duck is separated from their person, they may show signs of stress such as pacing, calling, reduced appetite, or withdrawal. These behaviors typically ease once the person returns, reinforcing the attachment-driven nature of the response.

Imprinted ducks may also show difficulty fully integrating socially with other ducks. They might struggle with normal flock dynamics, show delayed social behaviors, or appear unsure in duck-to-duck interactions. This does not mean they cannot live with other ducks, but their social reference point remains human-centered.

Taken together, these behaviors form a pattern rather than a single sign. Imprinting is best identified by consistency, intensity, and context. When a duck repeatedly treats you as their primary source of safety and orientation, imprinting is the most likely explanation.

Understanding these signs helps duck parents respond with empathy rather than confusion. These behaviors are not manipulative or accidental. They are the natural expression of an early-formed attachment that continues to guide the duck’s social world.

Is Imprinting Good or Bad?

Imprinting itself is neither good nor bad. It is a natural biological process designed to support survival during the earliest stage of life. The question is not whether imprinting is positive or negative, but whether the resulting needs of the imprinted duck can be met responsibly over the long term.

From a positive perspective, imprinted ducks often show a high level of trust toward humans. They are typically easier to handle, less fearful during routine care, and more tolerant of medical checks or environmental changes. This trust can be especially valuable in situations that require frequent human involvement, such as health monitoring or special care.

Imprinting can also create deep emotional bonds that many duck parents find incredibly meaningful. These ducks often seek interaction, respond to their person, and appear highly attuned to human presence. When supported appropriately, some imprinted ducks thrive in a mixed social environment where they feel secure with both humans and other ducks.

However, imprinting also carries challenges that should not be overlooked. Because the imprinted individual occupies a central role in the duck’s social framework, absence or inconsistency can be stressful. Some imprinted ducks experience separation related distress, particularly if their person is away for extended periods or routines change suddenly.

Social integration can also be more complex. An imprinted duck may struggle with normal flock relationships or show limited interest in duck-to-duck bonding. This can affect flock dynamics and may require careful management to ensure the duck remains socially fulfilled.

Another consideration is long-term dependency. Imprinted ducks often rely more heavily on human interaction for emotional regulation. This means the caregiver must be prepared for ongoing engagement, enrichment, and stability over the duck’s lifetime.

Imprinting becomes problematic only when it is unintentional or unsupported. When duck parents understand what imprinting is and plan accordingly, many of the potential downsides can be mitigated. Providing consistent routines, encouraging gradual flock interaction, and meeting the duck’s emotional needs all help create a balanced environment.

One of the most heartbreaking consequences of imprinting occurs when imprinted ducks are later abandoned or dumped. An imprinted duck does not perceive humans as optional companions. Humans are their primary source of safety, orientation, and social structure. When that bond is suddenly severed, the duck is left without the very framework their brain relies on to navigate the world. Even non-imprinted domestic ducks face overwhelming odds when released outdoors, lacking predator awareness, survival skills, and appropriate social support. For imprinted ducks, the situation is far worse. They may actively seek out people instead of shelter, fail to integrate with wild or feral ducks, and experience intense stress and disorientation. This is not a second chance at freedom. It is a near certain path to suffering and death. Dumping an imprinted duck is not just irresponsible. It is cruel.

Ultimately, imprinting is a responsibility rather than a mistake. When humans become central to a duck’s sense of safety and belonging, that role carries long-term significance. Recognizing this allows duck parents to make informed choices that prioritize the well-being of both the duck and the flock.

Can Imprinting Be Prevented?

In many cases, imprinting on humans can be reduced or avoided, but it requires intention from the very beginning. Because imprinting occurs during a short and highly sensitive developmental window, what happens in the first days of a duckling’s life has an outsized impact on long-term social behavior.

The most effective way to prevent human imprinting is early and consistent exposure to other ducks. Ducklings raised with siblings or peers are more likely to imprint on their own species because they receive the necessary social cues from one another. Even without an adult duck present, peer-raised ducklings often develop stronger duck-centered social bonds than those raised alone.

Limiting intensive one-on-one human interaction during the first days after hatch is also important. This does not mean neglecting care. Feeding, cleaning, and health checks are still essential, but handling should be purposeful rather than constant. The goal is to meet physical needs without becoming the duckling’s primary source of social comfort.

Visual and auditory exposure to adult ducks can further support species appropriate imprinting. Seeing adult ducks move, hearing their vocalizations, and observing flock behavior provides powerful social templates for the developing brain. These cues help guide the duckling’s understanding of what constitutes normal social structure.

Environmental design matters as well. Raising ducklings in groups, providing mirrors sparingly or not at all, and avoiding isolation all reduce the likelihood that a human becomes the sole social reference point. Social deprivation increases the brain’s reliance on whatever consistent figure is available.

That said, imprinting is not always preventable or even undesirable. Rescue ducklings, abandoned hatchlings, or ducklings requiring medical intervention often have no choice but to rely heavily on human care. In these cases, imprinting may be the safest and most humane outcome.

It is also important to recognize that prevention exists on a spectrum. Some ducks develop mild human bonding while still forming healthy relationships with other ducks. The goal is not to eliminate trust or familiarity, but to avoid exclusive dependence when possible.

Understanding how and when imprinting forms allows duck parents to make thoughtful choices. Whether preventing imprinting or supporting an imprinted duck, awareness and planning are the most important tools for raising emotionally healthy pet ducks.

Living With an Imprinted Duck

Living with an imprinted duck requires a shift in perspective. Rather than trying to undo imprinting, which is not realistically possible, the focus becomes meeting the duck’s emotional and social needs in a thoughtful and sustainable way. With the right approach, many imprinted ducks live stable and fulfilling lives.

Consistency is one of the most important factors. Imprinted ducks rely heavily on routine to feel secure. Predictable feeding times, regular interaction, and stable daily patterns help regulate stress and reduce anxiety. Sudden changes in schedule or long periods of absence can be more difficult for these ducks and may require gradual adjustment.

Introducing or maintaining flock companionship is often beneficial, even if the duck remains strongly bonded to a human. Some imprinted ducks take time to understand duck-to-duck social cues, but gentle exposure and patience can lead to improved integration. Allowing interactions to develop naturally, without forcing closeness, helps build confidence over time.

Environmental enrichment plays a key role as well. Providing access to water for swimming, foraging opportunities, safe exploration spaces, and mentally engaging activities helps redirect focus away from constant human attention. These experiences support natural behaviors and reduce reliance on a single social outlet.

Human interaction should remain present but balanced. Imprinted ducks often seek reassurance through proximity, and acknowledging that need builds trust. At the same time, encouraging independent activity and flock engagement supports emotional resilience. This balance helps prevent excessive dependency while still honoring the bond.

Observation is especially important with imprinted ducks. Changes in behavior, appetite, or vocalization may signal stress more quickly than in flock-oriented ducks. Being attentive allows for early intervention and adjustment before small issues become larger problems.

It is also helpful to plan for times when the primary caregiver is unavailable. Gradually introducing other trusted people, maintaining familiar routines, and ensuring flock stability can ease transitions. These preparations reduce stress for both the duck and the human.

Living with an imprinted duck is a long-term commitment rooted in responsibility and care. When humans become central to a duck’s sense of safety, that bond deserves respect and thoughtful management. With consistency, enrichment, and understanding, imprinted ducks can thrive while maintaining meaningful connections to both their humans and their flock.

Our Experience With Imprinting: Krümel and Muffin

Imprinting is not just a theoretical concept for us. It is something we live with every day through two very special ducks, Krümel and Muffin. Both are deeply bonded to me, and in both cases, the path to imprinting followed a remarkably similar pattern.

Krümel and Muffin each came to us as rescues at just one day old. At that age, a duckling is entirely dependent on external care, and in both situations, they arrived as single ducklings with no mother and no siblings. From a biological standpoint, the conditions for imprinting were already in place. Their brains were in that narrow, sensitive window, actively searching for safety and consistency.

Because they were so young and vulnerable, they grew up inside the house with us. I provided warmth, food, and constant supervision, which naturally led to a lot of close interaction. Feeding, brooder care, handling, and simply being present throughout the day meant that I became the most consistent and responsive figure in their early lives. Imprinting, in both cases, was not intentional. It was simply the safest and most humane way to raise a one day old rescue.

At the same time, we were very intentional about duck exposure. From the beginning, both Krümel and Muffin had daily interaction with our other ducks. They could see them, hear them, and spend supervised time with them. This was important to us because we wanted them to learn what other ducks are, how ducks move, and how ducks behave socially. That early exposure made a real difference in their long-term adaptability.

Muffin, in particular, spent a great deal of time with Krümel. The two formed a strong bond with each other, and that relationship has helped Muffin develop more duck-oriented behaviors. She is clearly attached to me, but she is also very connected to Krümel. In many ways, Krümel helped bridge the gap between human-centered imprinting and duck social learning.

Krümel, on the other hand, is very much my girl. She follows me closely, stays near me whenever possible, and prefers my presence over almost anything else. Her behavior often feels more human-centered than duck-centered. She seeks proximity, reassurance, and interaction in ways that clearly reflect imprinting. To her, I am not just part of the environment. I am her primary point of reference.

Muffin shows a slightly different balance. She is more duck-like in her day-to-day behavior, more comfortable within the flock, and more independent overall. At the same time, she still vocalizes when I am out of sight and chooses to sleep close to me when she is inside the house. The imprinting is there, but it expresses itself with a bit more flexibility.

Living with both of them has taught us that imprinting does not look the same in every duck. Even with nearly identical early life circumstances, individual personality plays a significant role in how that bond shows up later. What they share is trust, attachment, and a strong sense of safety with me.

Their stories also reinforce an important point. Imprinting does not mean a duck cannot learn how to be a duck. With thoughtful exposure, patience, and social opportunities, imprinted ducks can still develop healthy relationships within a flock. The bond with humans remains, but it does not have to exist in isolation.

Krümel and Muffin are a daily reminder that imprinting is both a responsibility and a privilege. When a duck chooses you as family during its earliest moments of life, that bond deserves understanding, respect, and lifelong care.

Final Thoughts

Imprinting is one of the most powerful and fascinating processes in a duck’s early life. It is driven by biology, shaped by environment, and expressed through deep and lasting attachment. When humans become part of that process, the bond that forms can feel extraordinary, and it truly is.

Understanding the science behind imprinting helps us see these relationships more clearly. It explains why some ducks bond so intensely to humans, why those bonds do not fade with age, and why imprinted ducks have unique emotional and social needs. Most importantly, it reminds us that these behaviors are not accidental or indulgent. They are the result of a perfectly functioning survival system.

For duck parents, knowledge is key. Whether imprinting is prevented, unavoidable, or already established, informed care makes all the difference. Supporting healthy flock relationships, providing consistency, and respecting the depth of the bond allows imprinted ducks to thrive.

For us, Krümel and Muffin embody both the science and the heart of imprinting. Their trust is humbling, their attachment is real, and their presence is a daily reminder of how deeply these birds experience the world around them.

Imprinting is not something to fear or romanticize. It is something to understand. When we meet it with intention and responsibility, it becomes one more way we can care for our ducks with the respect they deserve.

Related Articles

- Does my Duck Like Me? 12 Signs Your Ducks Love and Trust You

- Do Ducks Get Lonely? How to Keep Your Pet Ducks Happy and Social

- Duck Personalities – What They Reveal About Our Ducks (and Us!)

Connect deeper with your flock. Discover more about duck psychology and social dynamics in the Community & Behavior Hub.

References

- Bateson, P. (1966). The characteristics and context of imprinting. Biological Reviews, 41(2), 177–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1966.tb01489.x

- Horn, G. (2004). Pathways of the past. The imprint of memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1324

- American Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Early development and socialization of birds. https://www.avma.org