Duck Anatomy: A Complete Guide for Pet Owners

Last updated on October 11th, 2025 at 01:56 pm

When you live with ducks, you quickly realize just how remarkable their bodies are. From the soft waterproof feathers that keep them cozy on a rainy day to the wide bills that sift through water for tasty morsels, every part of a duck has a purpose. As both a duck mom and a scientist, I’ve learned that knowing a bit about duck anatomy not only deepens your appreciation for them but also helps you recognize when something isn’t quite right. In this guide, we’ll walk through the main external features of ducks and touch on their internal organs, with links to separate posts for those who’d like to explore systems like the respiratory or reproductive tract in more detail.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

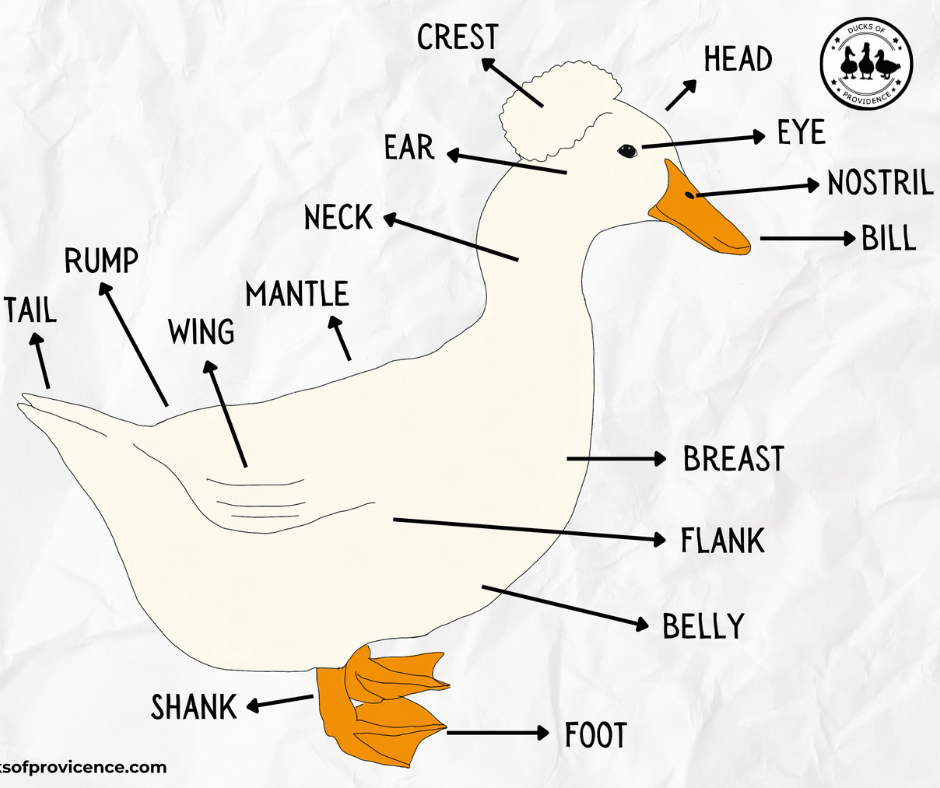

External Anatomy of a Duck

Before we look inside, it’s worth appreciating everything we can see on the outside. A duck’s external features, its bill, feathers, wings, legs, and tail, aren’t just for show. Each trait has a purpose, shaped by millions of years of evolution, and they all play a role in helping ducks thrive both in water and on land.

As duck keepers, learning the basics of external anatomy helps us notice when something looks unusual, like a swollen foot, missing feathers, or changes in the bill. It also deepens our admiration for the everyday things our ducks do, from wagging their tails in excitement to preening their waterproof feathers after a swim.

The Duck Head

The head is where so much of a duck’s personality shines through.

The Bill

The bill is one of the most distinctive features of a duck. Unlike chickens or geese, a duck’s bill is broad and flat, perfectly adapted for dabbling and filtering food from water.

- Lamellae: Along the inside edges are tiny, comb-like ridges called lamellae. These act almost like a kitchen strainer, allowing ducks to trap small seeds, insects, and plants while letting mud and water flow back out.

- Nail: At the very tip of the bill is a hard bump called the nail or bean. Ducks use this to dig into soil, peel bark, or break open small food items. You may have seen your ducks using it to scrape at the ground while foraging.

- Sensitivity: The bill is highly sensitive, full of nerve endings, which is why ducks can feel food in murky water. It’s a bit like having fingertips built into their mouths.

➡️ Want to learn more? See my full post on duck bills and how they work.

The Nostrils (Nares)

The two small openings on top of the bill are the nostrils, or nares.

- Ducks breathe through these openings, and because they’re positioned high on the bill, ducks can still breathe while the rest of their bill is underwater.

- They can also close their nares when diving, preventing water from flooding in.

- Healthy nares should be clean and open. Blocked nostrils can indicate respiratory illness or a sinus infection.

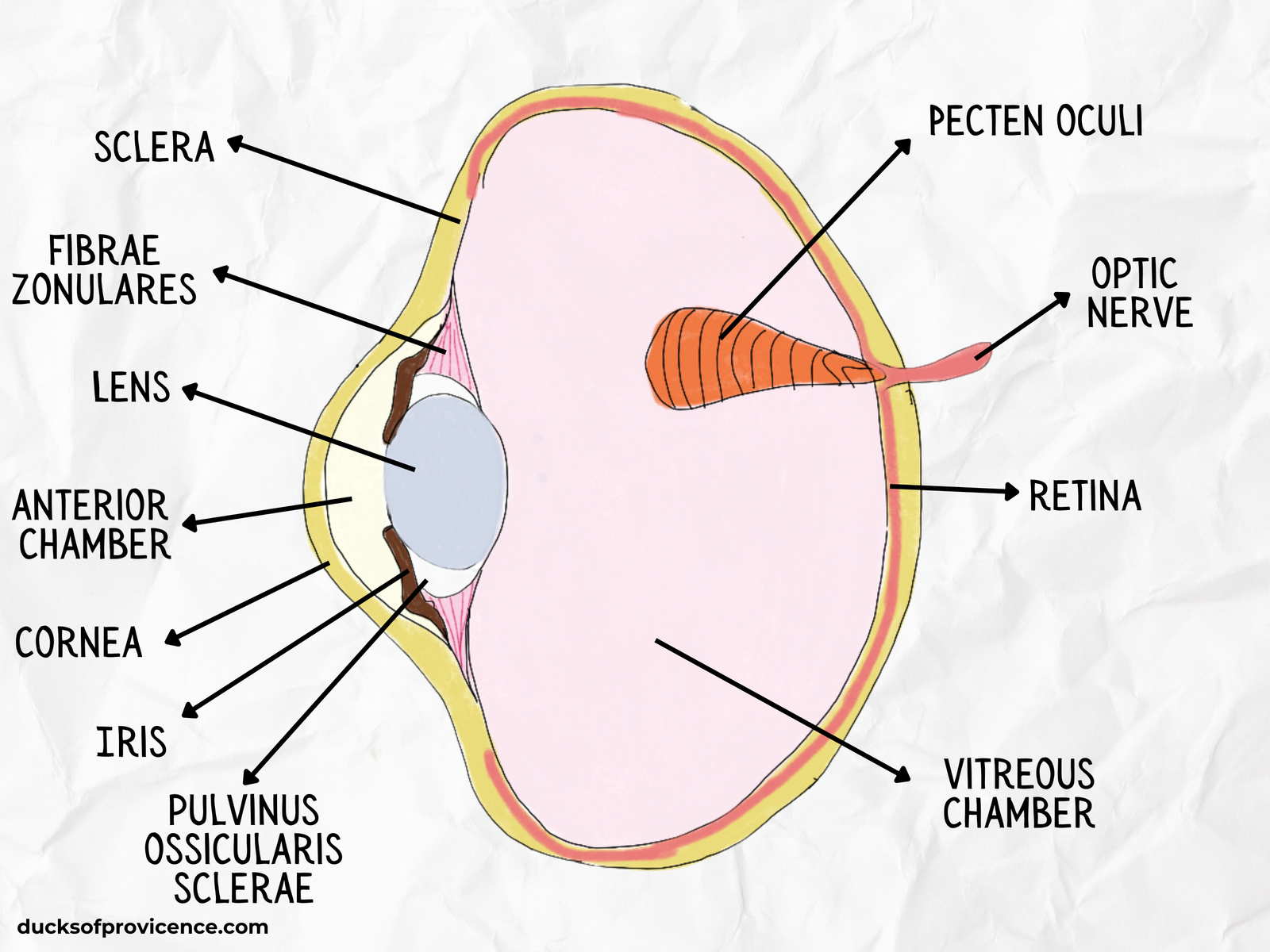

The Eyes

Ducks’ eyes are marvels of adaptation.

- Field of vision: With eyes set on the sides of their head, ducks can see nearly all around them, about 340 degrees. This wide field of vision is a crucial defense against predators.

- Color vision: Ducks see a broader range of colors than humans, including ultraviolet light. This allows them to detect patterns in plumage or food sources that are invisible to us.

- Eyelids and nictitating membrane: Ducks have three eyelids. The upper and lower lids close vertically, while a third eyelid, the nictitating membrane, sweeps across the eye horizontally. This thin, translucent lid protects the eye while swimming, almost like built-in goggles.

- Eye size and acuity: Ducks’ eyes are relatively large compared to their skull size, which enhances their vision and helps them spot danger quickly.

➡️ For a full dive into vision, check out my post on duck eyes and how they see the world.

The Brain and Skull

While not visible on the outside, the skull and brain are worth mentioning.

- Brain structure: Ducks have relatively large brains for their body size, especially in regions that control vision and movement. This supports their ability to navigate complex environments, form bonds, and learn routines.

- Skull features: Their skull is lightweight yet strong, protecting the brain while reducing overall head weight, which is important for balance during flight or swimming.

The Crest (in Some Breeds)

Some ducks, like White Crested Ducks, grow a fluffy feather pom-pom on their heads.

- Cause: This trait comes from a genetic mutation that affects how the skull develops. A fatty tissue “cushion” forms beneath the crest, which the feathers then grow out of.

- Special care: While adorable, the crest can sometimes make ducks more prone to injuries or neurological issues, so crested ducks may need extra monitoring.

➡️ Learn more about this unique trait in my post on crested ducks.

The Neck

A duck’s long, graceful neck is more than just elegant. It’s a multi-purpose tool that helps them eat, groom, and stay alert. Hidden beneath those feathers are twice as many neck bones as humans have, giving ducks incredible flexibility. From foraging underwater to tucking their bills under a wing for a nap, the neck is central to nearly everything a duck does each day.

Flexibility and Vertebrae

A duck’s neck may look simple, but it’s surprisingly complex. While humans have only seven cervical vertebrae, ducks have sixteen. This gives them remarkable flexibility, allowing them to bend, twist, and reach in almost any direction. You’ll often see your ducks using this range of motion to preen every feather on their body, shake off water after a swim, or dip deep into a pond to grab plants or bugs.

Feeding and Foraging

The long neck is a perfect adaptation for dabbling. Ducks can reach down into the water or mud while keeping most of their body afloat. This saves energy and helps them access food sources that might otherwise be out of reach. If you watch your ducks closely, you’ll notice they sometimes “tip up” with their tails in the air, another clever way the neck helps extend their reach.

Preening and Grooming

One of the most frequent uses of the neck is for preening. Ducks rely on their flexibility to spread oils from the preen gland at the base of their tail across their feathers. This not only keeps their feathers waterproof but also removes dirt and parasites. The neck acts like a built-in grooming tool, giving them access to every inch of their plumage.

Communication and Behavior

The neck is also central to duck body language.

- A stretched-out neck can signal curiosity or alertness.

- Rapid head bobbing, often with the neck extended, can be a courtship behavior in drakes.

- A tucked-in neck, with the head resting on the back or under a wing, usually means the duck feels safe and relaxed.

Understanding these subtle cues can help you read your ducks’ mood and needs.

The Wings

Even if your pet ducks rarely take to the sky, their wings are remarkable structures. Built for flight, balance, and communication, wings are covered in carefully arranged layers of feathers that keep ducks sleek and efficient. Watching a duck stretch, flap, or display its wings after a bath is a reminder of how much more these appendages do than just power flight.

Structure of the Wing

A duck’s wing is made up of bones similar to our arms: humerus, radius, and ulna, but modified for flight. The feathers attached to these bones are arranged in layers:

- Primary feathers: Long, outer feathers at the wing tips that provide thrust during flight.

- Secondary feathers: Found closer to the body, these help generate lift. In some breeds, these feathers display iridescent patches called speculums—those bright blue, green, or purple bands you see flashing in the sunlight.

- Coverts: Smaller feathers that overlap the bases of the primaries and secondaries, smoothing airflow and protecting the flight feathers underneath.

Even if your pet duck doesn’t fly much, their wings are still vital to balance, swimming, and display.

Flight Ability

Not all ducks are built the same when it comes to flying.

- Lightweight breeds: Mallards, muscovies, and other lighter ducks can take to the air with ease. Mallards in particular are strong fliers, which is one reason they’re the wild ancestors of most domestic ducks.

- Heavy breeds: Pekins, Silver Appleyards, and Saxonies are generally too heavy for sustained flight. They may manage a short flap and glide but prefer to stay grounded.

- Wing clipping: Some pet owners clip their ducks’ wings to prevent flying over fences, but this should be done with care. I usually prefer safe enclosures over wing clipping to let ducks keep their wings intact for balance and protection.

Balance and Swimming

Wings aren’t just for flying. Ducks use them as counterbalances when running, standing up from a resting position, or even making sharp turns in the water. During swimming, wings can act like rudders, helping them change direction quickly.

Communication and Displays

Ducks use their wings as part of their social language:

- Flapping: A full wing flap after preening or bathing helps realign feathers and shake off excess water, but it’s also a display of energy and well-being.

- Courtship: Drakes may raise their wings dramatically during mating rituals to show off their strength and feather quality.

- Defense: Ducks sometimes spread their wings wide to look larger and more intimidating when threatened.

Molting and Feather Care

At least once a year, ducks go through a molt, shedding old flight feathers and regrowing new ones. During this time, their flying ability may be reduced, and they can look a bit ragged. But molting is essential for maintaining healthy plumage. Pet duck owners quickly learn to expect the “messy” phase when feathers seem to be everywhere.

The Body and Feathers

A duck’s body may look rounded and soft, but it’s a finely tuned design for life in and around water. Feathers are at the heart of this design, providing warmth, waterproofing, and even camouflage. From the fluffy down that keeps them insulated to the sleek contour feathers that let them glide smoothly across a pond, every feather has a role to play.

Types of Feathers

Ducks carry several specialized feather types, each serving an important purpose:

- Contour feathers: The smooth outer feathers that give ducks their shape and color. They’re sleek and aerodynamic, helping ducks glide through water.

- Down feathers: Found beneath the contour feathers, these are soft and fluffy, trapping air close to the body for insulation. This is what keeps ducks warm, even in chilly weather.

- Flight feathers: The strong primaries and secondaries on the wings that power flight and help with maneuvering.

- Tail feathers: Provide balance and steering, especially in water.

Each feather has a central shaft with barbs and barbules that interlock like Velcro. When you see your duck “zip” a feather with its bill during preening, it’s reconnecting those tiny hooks to keep the feather waterproof and smooth.

Waterproofing and Preening

Ducks are famous for their waterproof coats, but it isn’t magic, it’s biology. At the base of the tail sits the uropygial gland (often called the preen gland), which produces an oily substance. Ducks spread this oil over their feathers using their bills, coating them so water rolls right off. Without regular preening, their feathers would lose waterproofing, making swimming dangerous.

Insulation and Temperature Control

Feathers aren’t just for waterproofing; they also help regulate body temperature. In winter, ducks fluff up their feathers to trap more insulating air. In summer, they flatten their feathers to release heat. This feather “thermostat” is one reason ducks are so hardy in a wide range of climates.

Feather Health and Molting

Healthy feathers are vital for survival. Frayed, dirty, or missing feathers can leave ducks vulnerable to cold, wetness, and even injury. Ducks replace their feathers in an annual molt, shedding old ones and growing fresh plumage. This process can look messy, but it’s perfectly normal.

➡️ For more details, see my posts on duck feathers and their many functions and molting in ducks.

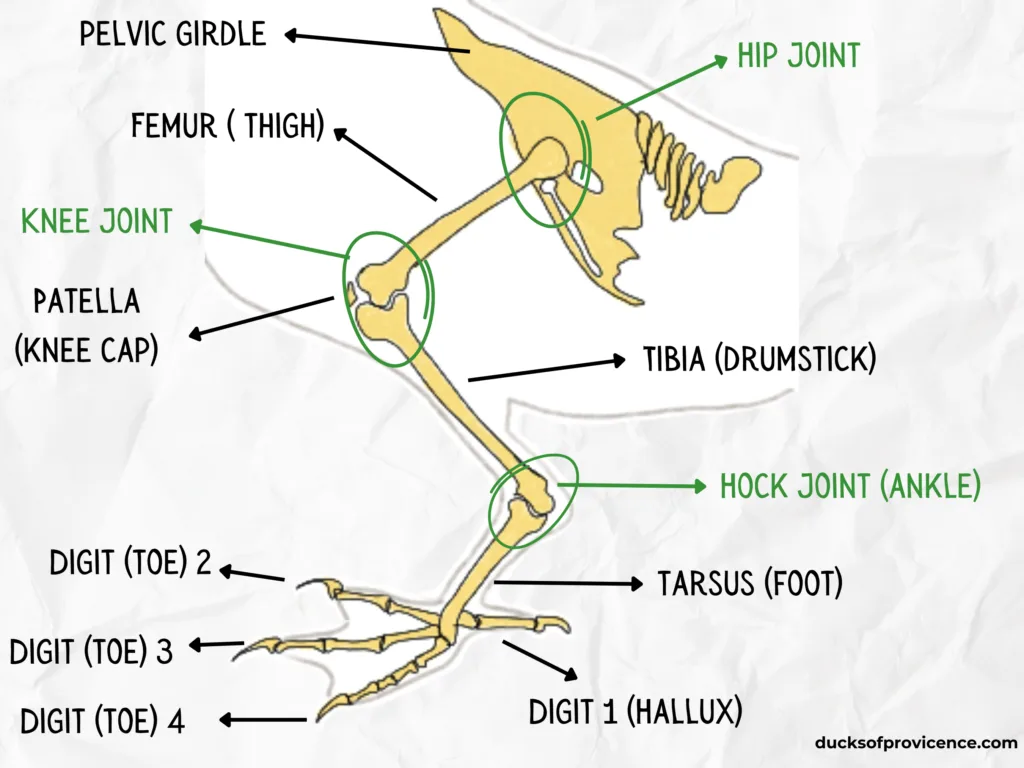

The Legs and Feet of a Duck

Those waddling steps and splashy paddles are powered by some impressive engineering. Ducks’ legs and feet are built for swimming, balancing, and regulating body temperature. With strong bones, tough scales, and distinctive webbing, they’re perfectly adapted for a semi-aquatic lifestyle. What might look like clumsy waddles on land become graceful strokes in water.

Structure and Position of Duck Feet

A duck’s legs are set farther back on its body compared to chickens or geese. This gives them their characteristic waddle on land but makes them powerful swimmers in the water. The bones are sturdy, built to handle both walking on uneven ground and paddling against currents.

- Bones: The main leg bones are the femur (thigh), tibiotarsus (shin bone), and tarsometatarsus (lower leg). These bones support the duck’s weight and absorb the impact of walking and landing.

- Tendons and gripping reflex: Ducks have strong tendons that run down the back of the leg. These tighten automatically when the leg bends, helping the toes curl. While ducks aren’t natural perchers, this reflex still aids in stability on uneven ground.

- Hidden joints: What many people think is a duck’s “knee” is actually the ankle joint (the hock). Their real knees, as well as their hip joints, are tucked up higher on the body and hidden beneath the feathers. This gives ducks their unique posture and gait.

Webbed Feet

One of the most recognizable features of ducks is their webbed feet.

- Swimming: The webbing acts like a paddle, spreading wide when pushing against water and folding together on the return stroke—much like a built-in pair of flippers.

- Walking: While webbing isn’t as efficient on land, it still gives ducks good stability, especially on soft or muddy ground.

- Cooling system: Ducks don’t sweat. Instead, they release heat through their legs and feet. In hot weather, you might notice them standing in cool water to regulate their body temperature.

Scales and Protection

The shanks and tops of the feet are covered in tough keratinized scales. These protect ducks from scrapes, cuts, and even cold weather. In freezing conditions, ducks can stand on ice without frostbite thanks to a special blood flow system called countercurrent heat exchange. Warm blood flowing down the leg warms the colder blood returning from the feet, conserving heat while preventing freezing.

Behavior and Use

- Ducks often use their feet to stir up mud or water while foraging, helping them uncover food.

- During mating, drakes use their feet for balance, which can sometimes result in scratches on the hen’s back (a reason many keepers use hen saddles during breeding season).

- Feet also play a role in social interactions. Kicking or slapping with the feet can be part of aggressive displays.

Health Concerns

Because ducks spend so much time walking on different surfaces, their feet can sometimes suffer from issues such as bumblefoot, a bacterial infection caused by small cuts or pressure sores. Hard or rough flooring in runs can make this more likely. Preventive care includes providing soft ground, clean bedding, and safe swimming areas.

➡️ For more, see my dedicated posts on duck feet and bumblefoot in ducks.

The Duck Tail

Small but mighty, the tail is one of the most expressive and functional parts of a duck. It helps steer in water, keeps balance on land, and even hides one of the most important openings in a duck’s body, the vent. A wagging tail often means a happy duck, while the famous curled feather in drakes makes tail feathers a handy way to tell males and females apart.

Structure and Feathers

The duck’s tail may look small compared to the rest of its body, but it plays a big role in balance and movement. The tail feathers help with steering in water and stability on land. When swimming, ducks use subtle tail adjustments like a rudder, while on land, the tail shifts to counterbalance the waddle of their legs set farther back.

- Drake feather: In males (drakes), one or more tail feathers curl upward into a distinctive loop, called the drake feather. This is a reliable way to tell males and females apart in most domestic breeds.

- Preen gland location: Just above the tail sits the uropygial (preen) gland, which produces the oils ducks use to waterproof their feathers. You’ll often see ducks bend around to rub their bills on this spot, then spread the oil across their plumage.

The Vent (Cloaca)

Beneath the tail, hidden under the feathers, is the vent—also called the cloaca. This is the single external opening used for three vital functions:

- Digestive: Waste (feces and urates) exits through the vent.

- Reproductive: In females, eggs pass through the vent after traveling down the oviduct. In males, the penis (phallus) everts from the cloaca during mating.

- Urinary: Birds don’t urinate separately—liquid waste mixes with feces before leaving the vent.

Healthy vents should stay clean and free of swelling, discharge, or signs of irritation. As duck keepers, checking the vent area is part of a good routine health check.

Communication and Behavior

The tail is also used in social signaling:

- During courtship, drakes sometimes display their tails alongside wing flaps to show off their condition.

- A duck wagging its tail rapidly is often showing excitement or happiness (many of us duck parents call this their “happy wag”).

- Tail flicks can also shake off water after a bath or swim.

Internal Anatomy Overview

While the outside of a duck shows us feathers, bills, and webbed feet, the inside tells an even more fascinating story. Ducks have many of the same organs we do. Hearts, livers, lungs, and intestines, but they’re arranged and adapted in ways that suit a semi-aquatic life. From air sacs that make breathing incredibly efficient, to gizzards that grind food without teeth, to the specialized reproductive system that produces eggs, every organ works together to keep a duck healthy and thriving.

Understanding these internal systems helps duck keepers recognize early signs of illness, appreciate just how remarkable their ducks really are, and provide the best possible care.

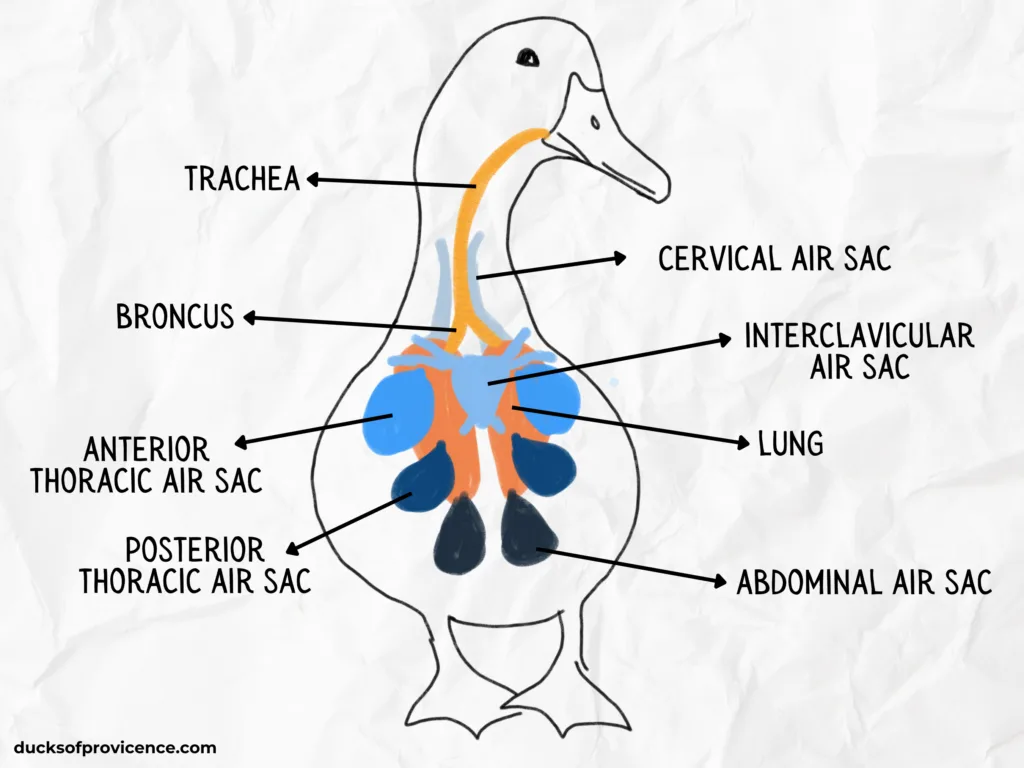

Respiratory System

Ducks don’t breathe quite like we do. While mammals rely on lungs that expand and contract, ducks (and other birds) use a flow-through system that allows for almost continuous oxygen exchange. This makes them far more efficient breathers than mammals.

Air Sacs and Lungs

- Ducks have nine thin-walled air sacs distributed throughout their body (cervical, clavicular, thoracic, and abdominal). These air sacs don’t exchange oxygen directly but act like bellows, moving air through the lungs.

- The lungs themselves are compact and relatively rigid. Instead of inflating, air flows one way through tiny tubes called parabronchi, where oxygen is absorbed into the blood and carbon dioxide is released.

- This one-way airflow means ducks receive oxygen both when they inhale and when they exhale, something mammals can’t do.

Efficiency in Action

This system is especially useful for:

- Flight: Even though many domestic ducks don’t fly far, their wild relatives migrate thousands of miles. The flow-through system ensures a steady oxygen supply during strenuous activity.

- Swimming and dabbling: Ducks often dip their heads underwater to forage. Because their breathing is so efficient, they can manage short dives without tiring easily.

- Heat control: Ducks don’t sweat. Instead, their respiratory system helps cool them down. On hot days, you may see your ducks panting with their bills open—this increases airflow over moist surfaces in the mouth and airways, releasing heat.

Vulnerabilities

Because of how delicate the air sacs are, ducks are sensitive to environmental conditions:

- Dust and mold spores from bedding or feed can irritate their respiratory system and cause infections.

- Ammonia buildup from soiled bedding is especially harmful to their airways.

- Respiratory infections can spread quickly once air sacs are involved, since the system circulates air throughout the body.

Signs of Trouble

As duck keepers, it’s important to watch for:

- Open-mouth breathing or panting (outside of hot weather).

- Wheezing, rattling, or “snicking” sounds.

- Discharge from the nares (nostrils).

- Swelling around the eyes or sinuses.

➡️ For a deeper explanation, including illustrations of the air sacs, see my full post on the duck respiratory system.

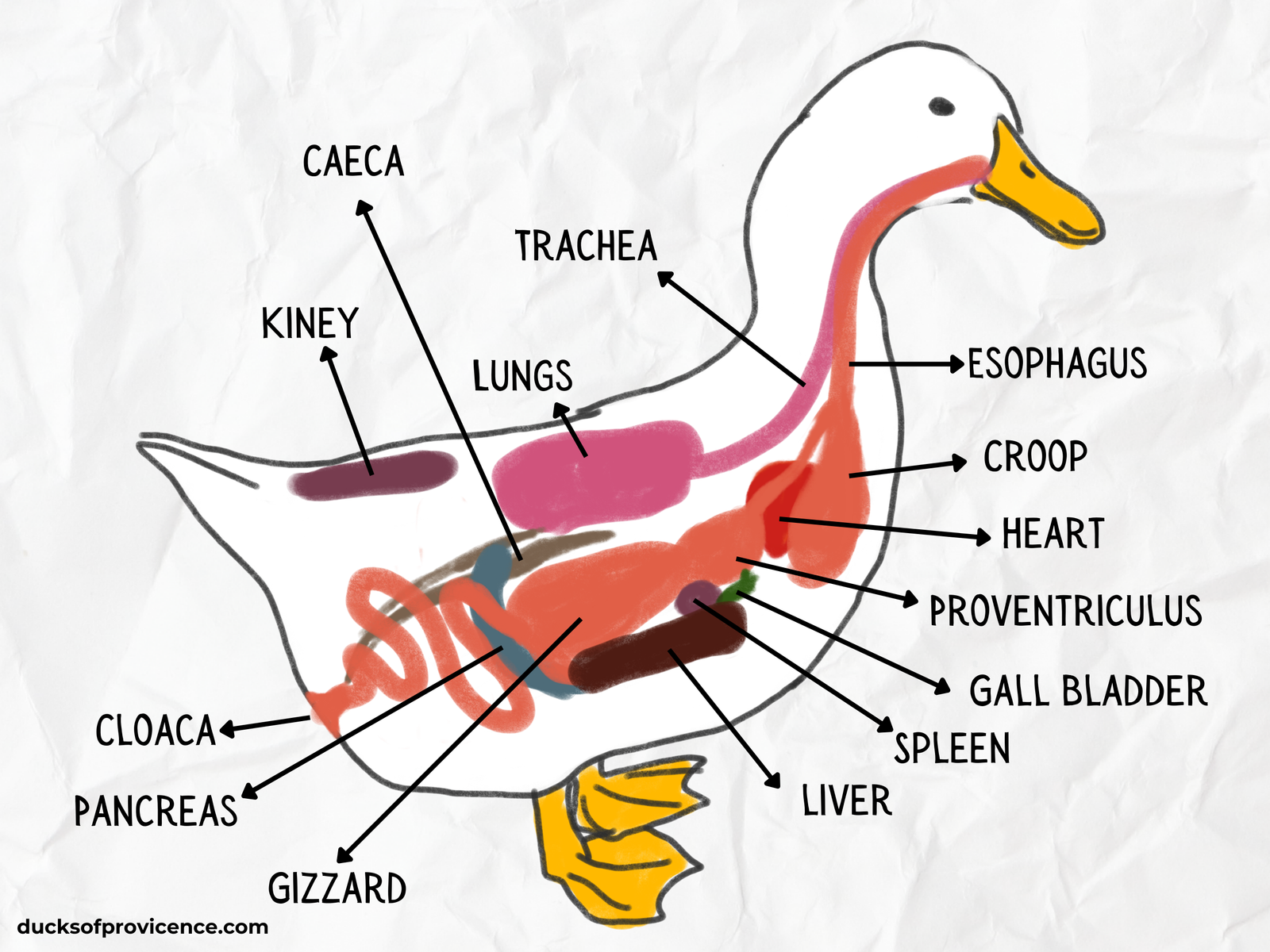

Digestive System

Ducks are omnivores with a digestive system built to handle everything from tender greens to crunchy grains and even the occasional insect. Understanding how food moves through their body helps us appreciate why ducks need grit, why they’re always dabbling in water, and why diet has such a direct effect on their health.

From Bill to Esophagus

Digestion begins with the bill, where lamellae (those comb-like ridges) help strain edible bits from mud or water. Unlike mammals, ducks don’t chew, food is swallowed almost whole. Their saliva moistens food and starts breaking it down as it moves into the esophagus, a flexible tube running down the neck.

Along the esophagus is a small pouch called the crop. Ducks do have a crop, just like chickens, but it’s less developed and not as prominent. Food usually doesn’t stay there long. It quickly moves along to the next stages of digestion. This is why you don’t see the same large “full crop bulge” in ducks that you often notice in chickens.

The Proventriculus (True Stomach)

Next, food enters the proventriculus, sometimes called the glandular stomach. Here, digestive enzymes and acids are secreted to begin chemical digestion. This step is crucial for softening grains, insects, and plant material before they reach the next chamber.

The Gizzard (Ventriculus)

The gizzard is a muscular organ that acts like a grinding mill. Because ducks don’t have teeth, they rely on grit (tiny stones or commercial grit) stored in the gizzard to crush and pulverize food.

- Soft foods (like lettuce or peas) pass through easily.

- Hard grains or fibrous plants are broken down with the help of grit.

You’ll sometimes see ducks nibbling at gravel or small stones. That’s them gathering the tools their gizzard needs to do its job.

The Intestines

From the gizzard, food moves into the small intestine, where most nutrient absorption takes place. The pancreas and liver supply enzymes and bile to help break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

- The small intestine is where vitamins, minerals, and energy are absorbed into the bloodstream.

- The ceca, two blind pouches branching off the intestine, help ferment tougher plant material. Ducks often pass a darker, smellier “cecal poop” once or twice a day. Perfectly normal, even if it looks alarming at first!

- The large intestine reabsorbs water before waste exits the body.

The Cloaca (Vent)

All digestive waste leaves the body through the vent, which also serves the urinary and reproductive systems. Ducks don’t urinate separately. Instead, uric acid (the white part of droppings) mixes with feces before being expelled.

Why This Matters for Duck Owners

- Grit: Domestic ducks without access to natural foraging should always have access to grit. Without it, their gizzards can’t grind food effectively.

- Diet: A balanced diet supports the liver, pancreas, and intestines in doing their jobs. Too much bread or starchy food overwhelms the system.

- Observation: Duck poop may not be glamorous, but it’s one of the best windows into their digestive health. Changes in color, consistency, or frequency can be early warning signs of illness.

➡️ For a full explanation, see my post on the duck digestive system.

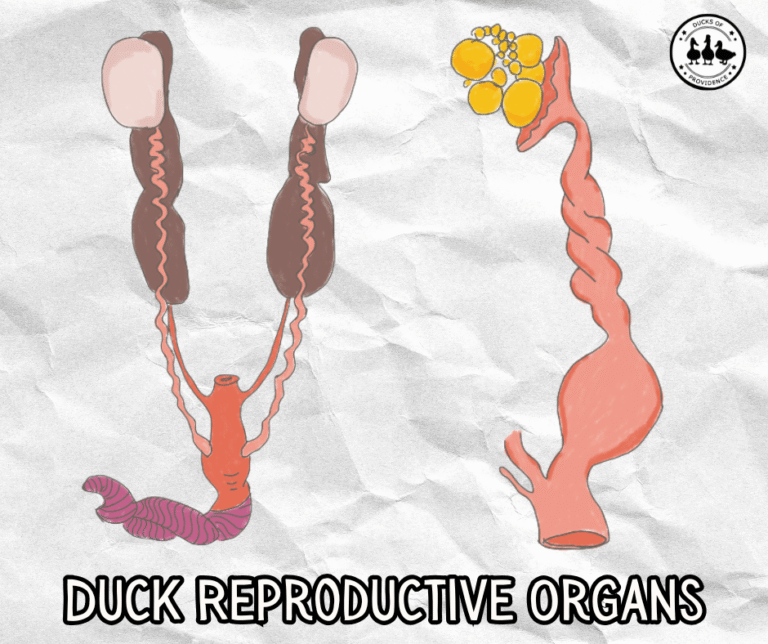

Reproductive System in Ducks

Ducks have a fascinating reproductive system that sets them apart from many other birds. Whether it’s the complex process of egg formation in hens or the unusual anatomy of drakes, understanding how reproduction works can help us better care for our flocks and recognize when something isn’t quite right.

Female Reproductive System

- Single ovary: Unlike mammals, female ducks have only one functioning ovary (the left). This reduces weight for flight while still producing enough eggs for reproduction.

- Egg development: Inside the ovary are thousands of tiny ova (yolks in waiting). When an egg is released, it travels into the oviduct, a long, coiled tube where the egg is built layer by layer.

- Infundibulum: The funnel-like entrance where the yolk is captured. Fertilization occurs here if a drake is present.

- Magnum: Adds layers of albumen (the egg white).

- Isthmus: Forms the inner and outer shell membranes.

- Uterus (shell gland): The egg spends the most time here, as the shell is laid down. Pigments that give eggs their colors (white, green, blue, gray, or black in some breeds) are added here as well.

- Vagina: The egg passes through before being laid via the vent.

- Laying cycle: The entire process from yolk release to a fully shelled egg takes about 24–26 hours.

➡️ For more details on this process, see my post on how eggs are made in ducks or on duck reproductive organs.

Male Reproductive System

Drakes are unusual among birds because they have an intromittent organ (penis), something most bird species lack.

- Testes: Located inside the body cavity, testes enlarge dramatically during breeding season.

- Phallus: The penis (technically called the phallus) everts from the cloaca during mating. It’s corkscrew-shaped, which matches the equally complex structure of the hen’s oviduct.

- Seasonality: In many breeds, drakes’ testes shrink outside the breeding season, reducing fertility until the next spring.

Fertility and Behavior

- A fertile egg is created only if a hen mates with a drake and sperm reaches the infundibulum at the right time. Otherwise, hens still lay eggs. They’re simply infertile.

- Ducks often form seasonal pair bonds. Drakes may show courtship behaviors like head bobbing, wing flapping, and gentle nibbling of the hen’s neck.

- Overmating can sometimes cause stress or injury in hens, which is why flocks should have a balanced hen-to-drake ratio (ideally 4–5 hens per drake).

Why It Matters for Duck Owners

Fertility: For those incubating eggs, knowing how and when fertilization happens increases hatching success.

Reproductive health: Issues like egg binding, soft-shelled eggs, or infections can be life-threatening if not recognized early.

Hormonal cycles: Understanding seasonal changes in both hens and drakes helps explain shifts in behavior (like sudden aggression or loud calling).

Circulatory System and Vital Organs

Ducks, like all birds, have a compact but highly efficient set of organs that keep their bodies running. These organs may be hidden beneath feathers, but their health has a huge impact on your duck’s well-being.

The Heart

Ducks have a four-chambered heart, just like humans. This design keeps oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood completely separate, allowing efficient circulation.

- High activity support: Whether flying, swimming, or running, ducks need a steady supply of oxygenated blood. Their heart is proportionally larger than a mammal’s of the same size, supporting bursts of energy.

- Circulatory speed: This efficiency is also what allows them to maintain higher body temperatures (around 106 °F / 41 °C), which is normal for birds.

The Liver

The liver is a multitasking organ critical to duck health.

- Metabolism: It helps break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates from food.

- Detoxification: It filters out harmful substances, including toxins and heavy metals, a function especially important if ducks accidentally ingest something they shouldn’t.

- Storage: The liver stores vitamins and minerals for later use.

Because the liver is central to so many processes, problems often show up in bloodwork when ducks are ill.

The Pancreas

Nestled between the loops of the small intestine, the pancreas produces enzymes that aid digestion and hormones like insulin that regulate blood sugar. If the pancreas is inflamed or stressed, digestion and energy balance can both suffer.

The Kidneys

Ducks have paired kidneys that filter waste products from the blood and balance water and electrolytes. Unlike mammals, ducks excrete nitrogen waste as uric acid, which mixes with feces and gives droppings their white, pasty portion.

- Kidney function is vital for hydration and overall balance.

- Dehydration or exposure to toxins (like too much salt or metals such as zinc) can quickly overwhelm the kidneys.

Other Organs of Note

- Spleen: Supports immune function and blood cell regulation.

- Gallbladder: Stores bile made by the liver to aid in fat digestion.

- Adrenal glands: Small glands near the kidneys that produce hormones controlling stress and metabolism.

These vital organs may not be as visible as wings or feet, but their health is often reflected in your duck’s behavior. Lethargy, poor appetite, or changes in droppings can all signal something going on inside. As duck keepers, having a general understanding of these systems helps us know when it’s time to call a vet.

Why Anatomy Matters for Duck Owners

Understanding your duck’s anatomy isn’t just an exercise in curiosity. It’s an important part of being a responsible duck parent. When you know how your duck’s body is put together and how each system works, you can:

- Spot problems early: A limp might point to leg or foot issues, while a change in breathing could signal a respiratory problem.

- Provide better care: Knowing about the gizzard reminds us why grit is essential, while understanding feather waterproofing explains why access to water for preening is non-negotiable.

- Strengthen your bond: Watching your ducks with a bit of biological insight makes their daily behaviors, like tail wags, wing flaps, or preening sessions, even more fascinating.

The more you learn about what’s going on beneath the feathers, the more confident you’ll feel in keeping your ducks happy and healthy.

Did You Know? Special Features of Ducks

Ducks may look simple on the outside, but their bodies hold some truly remarkable adaptations that set them apart from many other animals:

- Super Breathers: Ducks have nine air sacs that keep oxygen flowing in one direction through their lungs, so they get oxygen both when breathing in and out.

- Built-In Filters: Tiny comb-like ridges inside their bills, called lamellae, let them filter seeds and insects from water and mud.

- Underwater Goggles: Ducks have a nictitating membrane, a third eyelid that slides sideways across the eye, protecting it while they swim.

- All-in-One Exit: The cloaca (vent) is used for digestion, reproduction, and waste removal, everything in one spot.

- Unique Drakes: Male ducks are among the very few birds with a penis (phallus), and theirs is corkscrew-shaped!

- Waterproofing Oil: The preen gland near the tail makes oil that ducks spread over their feathers to stay waterproof.

- Warm Feet on Ice: Special blood flow in their legs, called countercurrent heat exchange, lets ducks stand on frozen ponds without getting frostbite.

- Cecal Poop: Those extra-dark, stinky droppings every so often? That’s cecal poop, a normal by-product of fermenting plant material in their paired ceca.

These features show just how specialized ducks are for their lifestyle in and around the water.

Final Thoughts

Ducks are extraordinary creatures. On the surface, they may seem like simple, waddling companions, but their anatomy reveals a masterpiece of adaptation. From air sacs that let them breathe efficiently, to specialized bills built for filtering, to feathers that insulate and repel water.

As pet duck owners, we get the privilege of observing these features up close every day. Whether it’s the gentle wag of a happy tail, the flash of iridescent feathers in the sun, or the miracle of an egg appearing in the nest box, each moment reminds us how remarkable these birds truly are.

By understanding duck anatomy, inside and out, we not only become better caretakers. We also deepen our appreciation for the little details that make our feathered friends so unique.

Other Posts from the Duck Anatomy Category

- The Duck Bill – Anatomy, Function, and Differences

- Duck Feet Facts: Key Anatomical Features And Functional Adaptations

- The Duck Respiratory System: Airways, Lungs, and Air Sacs in Detail

- Duck Digestive System Anatomy

- Duck Eye Facts: How Ducks See the World Differently

- The Science Behind Duck Feathers: Anatomy, Function & Care

- Male and Female Duck Reproductive Systems

- Duck Diagnostic Chart: Vital Signs, Tests, and What Your Duck’s Poop Is Telling You

References

- LafeberVet: Waterfowl Anatomy & Physiology Basics

- Lucy, K.M., Karthiayini, K. (2022). Anatomy and Physiology of Ducks. In: Jalaludeen, A., Churchil, R.R., Baéza, E. (eds) Duck Production and Management Strategies. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6100-6_4