Avian Influenza and Backyard Ducks: What You Need to Know in 2025

Last updated: March 1st, 2026

The words avian influenza might sound like something only commercial farms need to worry about, but for backyard duck keepers like us, it’s important to stay informed. As the virus continues to make headlines, including concerning developments in both poultry and dairy farms, we owe it to our flocks to understand the risks and take proactive steps to keep them safe.

Let’s walk through the current situation, how it affects ducks, what symptoms to look for, and what we as humans need to consider.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

Part of the Duck Health & Anatomy Hub, Evidence-based medical resources and anatomical research.

- What Is Avian Influenza?

- Recent Developments in 2025

- How Does This Relate to Backyard Ducks?

- Symptoms to Watch For in Ducks

- What Happens When You Report a Case to the USDA?

- The Dilemma We Face as Pet Duck Owners

- Biosecurity: Your Best Line of Defense of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

- Monitor Outbreaks Near You

- Ducks vs. Other Poultry: Are They Different?

- Can Humans Get Sick?

- Final Thoughts

- Related Articles

What Is Avian Influenza?

Avian influenza (AI), commonly referred to as bird flu, is a highly contagious viral infection that primarily affects birds, especially waterfowl like ducks, geese, and swans. The disease is caused by influenza type A viruses, which circulate naturally among wild birds but can also spill over into domestic poultry and even, on rare occasions, into mammals, including humans.

Avian influenza viruses are classified by two proteins on their surface: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Different combinations of these proteins result in various subtypes: H5N1 and H5N9 are two of particular concern.

Two Main Forms of Avian Influenza

AI viruses exist in two general forms, defined by their pathogenicity, which is essentially how sick they make birds:

Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI):

This form typically causes mild or no symptoms in infected birds. It can circulate quietly in a flock or wild bird population for some time, occasionally mutating into a more dangerous version. While not as alarming as its counterpart, LPAI can still impact bird health and productivity, especially in stressed or immunocompromised birds.

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI):

This form is far more dangerous and can cause sudden death, rapid spread, and severe disease, especially in chickens and turkeys. Symptoms may include respiratory distress, swelling of the head, drop in egg production, and neurological signs. In ducks, though, symptoms are often much more subtle, or even completely absent, which is one of the reasons they’re such important carriers.

Spotlight on Subtypes: H5N1 and H5N9

H5N1: The Most Notorious

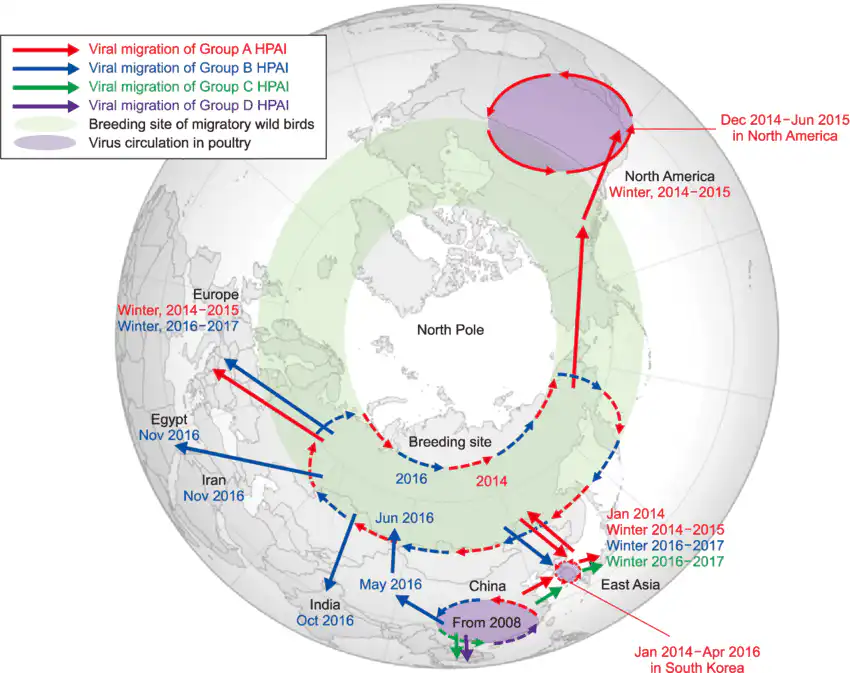

The H5N1 subtype is currently the most widespread and lethal strain of HPAI. First identified in geese in China in 1996, H5N1 has since spread across the globe, infecting wild birds, backyard flocks, commercial poultry operations, and even mammals. In 2025, this strain is the main culprit behind the widespread outbreaks we’re seeing in the U.S. and beyond.

- Why it matters for duck keepers:

Ducks, especially mallards and other wild species, can carry H5N1 without showing symptoms, making them a hidden reservoir. They can shed the virus in saliva, nasal secretions, and feces, spreading it in shared water sources and feeding areas. - Human health connection:

While human infections are rare, they can be severe or even fatal. Most known cases have occurred in people with close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments.

H5N9: Less Common, But On the Radar

H5N9 is another subtype of avian influenza that has caused outbreaks in poultry, though it’s less common than H5N1 and has not been linked to significant human infections to date. It tends to emerge sporadically and, in many cases, behaves like an LPAI virus. However, like other H5 strains, it holds the potential to mutate into a more virulent form.

- Why it’s worth mentioning:

While H5N9 hasn’t been a major player in recent U.S. outbreaks, its history of appearing in Asia and parts of Europe reminds us that influenza viruses are constantly evolving, and new strains can emerge when we least expect them.

Ducks: Natural Carriers and Silent Spreaders

Ducks, especially wild migratory species, play a central role in the ecology of avian influenza. They often harbor the virus without any outward signs of illness, allowing it to spread silently across large distances through migration, water contamination, and interaction with domestic birds.

Even among domestic ducks, signs can be mild or nonexistent, making it crucial for duck keepers to stay alert and implement strong biosecurity measures, particularly during migration seasons or when outbreaks are reported nearby.

Recent Developments in 2025

This year has brought a wave of significant and at times sobering developments in the ongoing battle against avian influenza. What started as a concern for poultry farms has now expanded into uncharted territory, with the virus affecting backyard flocks, commercial poultry, dairy cattle and even resulting in rare but tragic human cases.

First Human Death in North America

In early April 2025, Mexico confirmed its first human death from H5N1, a heartbreaking case involving a three-year-old girl from Coahuila (Reuters, 2025). While human infections remain rare, this incident serves as a stark reminder of the virus’s potential danger and the importance of vigilance, especially for those in direct contact with animals.

Widespread Outbreaks Across the U.S.

In the United States, H5N1 continues to spread across poultry populations. As of spring 2025, over 166 million birds in all 50 states have been affected by outbreaks since the virus reemerged in 2022 (CDC.gov, 2025).

This includes both large commercial farms and smaller backyard flocks. Recent reports have confirmed new cases in California and several Midwestern states, highlighting the vulnerability of small-scale operations that may lack the resources for intensive biosecurity (San Francisco Chronicle, 2025).

H5N1 Moves into Dairy Cattle

In a startling turn of events, dairy farms have now entered the picture. In early 2025, the USDA confirmed the presence of H5N1 in dairy herds in Texas, Kansas, and Nevada, among other states. This was previously unheard of, and while cows are not traditionally considered susceptible to avian influenza, the discovery suggests the virus may be adapting to infect new hosts.

Further investigation revealed that a new genotype of the virus—D1.1—had jumped from wild birds into dairy cattle in Nevada. This strain had been circulating in birds and mammals over the winter and appears to be replacing older genotypes in these outbreaks (USDA APHIS, 2025).

On affected farms, cows showed signs of decreased appetite and lower milk production, and nearly 90% of animals in one herd tested positive. Even non-lactating cows had antibodies, suggesting the virus was circulating widely within the herd (CIDRAP, 2025).

First Mammal-to-Human Transmission in the U.S.

In April 2024, the CDC confirmed a human case of H5N1 in a person who had been exposed to infected dairy cattle in Texas. This marked the first likely case of mammal-to-human transmission of the virus in the U.S., although human-to-human spread has not been documented. The case has raised new concerns about how the virus might evolve and whether it could eventually pose a greater risk to people in close contact with livestock (CDC, 2025).

Setbacks in Testing and Surveillance

Adding to the concern, the FDA recently suspended a key program aimed at improving bird flu testing in dairy products, including milk and pet food. The program, which was still in early stages, was cut due to staffing reductions. While pasteurization is believed to neutralize the virus in milk, this suspension could impact our ability to monitor and respond quickly to contamination concerns in the food supply (Reuters, 2025).

These developments illustrate just how adaptive and unpredictable avian influenza has become. From chickens to cows, and tragically, even to people, the virus is reminding us that it doesn’t stay in one lane. For those of us with ducks in our care, understanding this evolving situation helps us stay prepared, informed, and proactive in protecting our flocks.

How Does This Relate to Backyard Ducks?

For those of us caring for ducks at home, avian influenza isn’t just a problem happening somewhere else. It’s a real and present risk. Our backyard ducks, especially those with access to the outdoors, are uniquely vulnerable to the virus, even if they seem perfectly healthy. But why exactly are pet ducks at risk?

Wild Waterfowl Are Natural Reservoirs

Many species of wild ducks and geese, especially mallards, are natural carriers of avian influenza viruses, including H5N1. These birds can shed the virus through saliva, nasal secretions, and droppings without showing any signs of illness. That means they can be infected, fly hundreds of miles, land in a pond behind your home, and unknowingly leave the virus behind.

Because backyard ducks are genetically and behaviorally similar to their wild cousins, they’re especially susceptible to infection through shared spaces and natural foraging behavior.

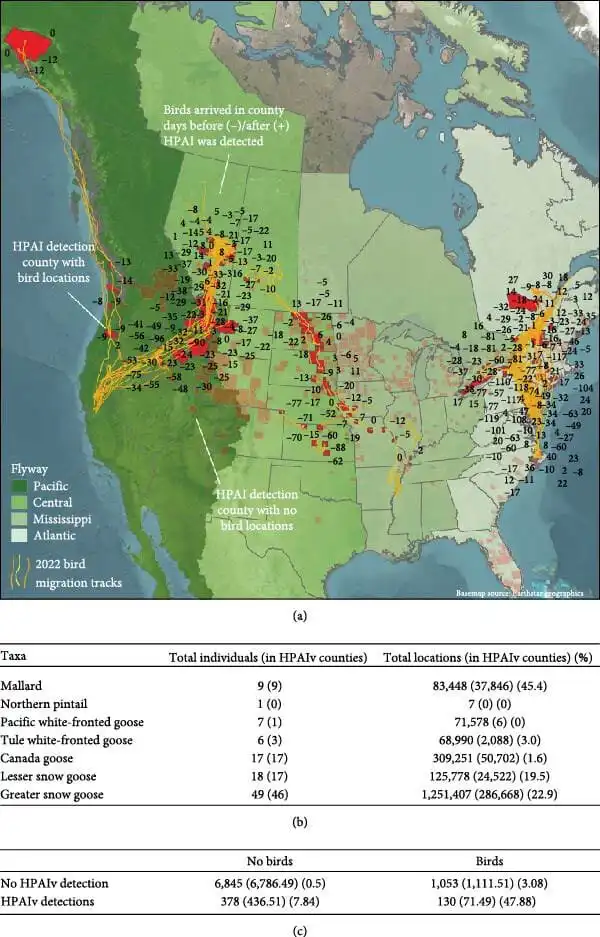

Migratory Flyways Cross Residential Areas

One of the key reasons backyard ducks are exposed is due to overlapping migratory flyways. In the United States, there are four main migratory routes that birds follow: the Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic Flyways. Texas sits squarely along the Central Flyway, a major route for millions of migrating waterfowl each spring and fall.

At my own home in North Texas, I regularly see mallards and wood ducks year-round, and each winter, American wigeons, lesser scaup, and Canada geese stop by our pond before heading north again in the spring. While it’s a joy to witness these migrations, it also brings a seasonal spike in avian influenza risk, especially when infected birds rest, feed, and preen near domestic flocks.

➡️ Learn more about duck migration

Shared Ponds and Water Sources Spread the Virus

Ducks are water birds, no surprise there! But their love for bathing, dabbling, and drinking from open water sources increases the potential for virus exposure. If wild birds contaminate a pond or water trough, your ducks could easily become infected through direct contact or ingestion.

Even small backyard water features or shared puddles can become hotspots for transmission, especially if droppings from wild birds aren’t cleaned promptly or if biosecurity practices are lax.

The Backyard Connection

Backyard setups often include open pens, free-ranging time, or partially covered runs, which can leave flocks exposed to wild visitors. Wild birds may perch on fences, share feeders, or sneak sips from your ducks’ water bowls. Even if they don’t land in the run, airborne droplets or contaminated surfaces (like feeders or nearby soil) can spread the virus indirectly.

What Makes Ducks Different From Chickens?

Unlike chickens, who often show immediate and severe symptoms of HPAI, ducks can appear perfectly normal while shedding the virus. That makes them silent spreaders, and harder to detect until it’s too late. In a mixed-species flock, this can put chickens, turkeys, or other poultry at even greater risk, especially if biosecurity practices aren’t duck-proof.

In short, if your ducks spend time outdoors, and most happy ducks do, it’s important to recognize that they’re on the front lines of avian influenza exposure. But don’t panic! With informed precautions, we can still give our flocks access to fresh air, water, and enrichment while minimizing risk. I’ll walk you through those biosecurity steps next.

Symptoms to Watch For in Ducks

One of the most challenging aspects of avian influenza in ducks is that not all infected ducks show signs of illness. In fact, many wild and even domestic ducks can carry and shed the virus silently, which is why it can spread so quickly before anyone realizes there’s a problem.

However, when symptoms do appear, especially in domestic breeds, they can escalate quickly and be severe. Early detection can make all the difference in preventing the virus from spreading to other birds in your flock or community.

Here’s what to look out for:

Common Signs of Avian Influenza in Ducks

- Sudden, unexplained death

This is often the first, and unfortunately, only sign in fast-moving outbreaks, especially in breeds that are more vulnerable. - Swelling around the eyes, head, neck, or throat

Infected ducks may develop puffiness or swelling, particularly around the eyes and face, sometimes making them appear sleepy or unwell. - Nasal discharge

Watery or cloudy mucus around the nares (nostrils) can indicate respiratory issues. You may also notice frequent head shaking as they try to clear their airways. - Sneezing, coughing, or labored breathing

Respiratory symptoms often present as open-mouthed breathing, wheezing, or odd vocalizations. In advanced cases, ducks may hold their necks out to breathe or make clicking noises when exhaling. - Purple or blue discoloration of the bill

A telltale sign of low oxygen levels in the bloodstream (cyanosis). While chickens show this in their combs, ducks don’t have combs, so discoloration of the bill or legs is more relevant. - Bluish coloration of the eyes

Some infected ducks may develop a cloudy or bluish tint in the iris, a subtle but important visual cue that something is off. - Drop in egg production or soft-shelled eggs

If your laying ducks suddenly stop producing or begin laying oddly shaped or thin-shelled eggs, it may be a sign of internal illness or reproductive stress due to infection. - Lethargy or weakness

Sick ducks often isolate themselves, stand still with eyes closed, or appear hunched and puffed up. - Uncoordinated movement or loss of balance

In some cases, avian influenza affects the nervous system, leading to tremors, head tilting, or a wobbly, staggering gait.

➡️ Learn more about Avian Influenza in ducks in our other article.

Notes on Species Differences

It’s worth noting that symptoms may vary based on breed and age, and not all ducks will show every symptom listed. Also, since ducks don’t have combs like chickens do, you won’t see the typical comb discoloration that’s often reported with avian influenza in other poultry. Instead, keep a close eye on the bill, eyes, and general posture for clues.

When to Take Action

If you notice any of the above signs, especially if multiple ducks in your flock are showing symptoms at the same time or one dies unexpectedly, treat it as an emergency.

- Isolate the affected duck(s) immediately if possible.

- Contact your avian vet or local animal health authority.

- Report the case to your state’s animal health department or the USDA’s toll-free line at 1-866-536-7593.

Prompt action helps prevent wider spread and could be critical in saving your flock and others nearby.

What Happens When You Report a Case to the USDA?

1. Initial Contact and Information Gathering

When you call the USDA at 1-866-536-7593 or report through your state veterinarian, they’ll:

- Ask for details about the birds, symptoms, recent deaths, and your location.

- Ask whether your flock has had any contact with wild birds, other poultry, or new additions.

- Possibly request photos or videos of the sick birds if available.

💡 Tip: The more details you can give (symptoms, flock size, exposure risks), the quicker they can assess the situation.

2. A State or Federal Vet May Be Dispatched

If the case sounds suspicious for HPAI (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza), they may:

- Send a state or USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) veterinarian to your property.

- Collect samples (swabs from the throat or cloaca) from live or deceased birds for laboratory testing.

These samples are usually sent to a National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) lab for confirmation.

3. Lab Testing and Diagnosis

Lab testing confirms whether the avian influenza virus is present, and if so, which strain (e.g., H5N1, H5N9, etc.). Results can take anywhere from 24–72 hours, depending on urgency and location.

4. If Positive: Containment and Quarantine

If HPAI is confirmed, several steps follow:

- Your flock may be placed under a quarantine order.

- Infected or exposed birds are humanely euthanized to prevent further spread (this can be heartbreaking, but it’s standard protocol in confirmed cases).

- The USDA may provide assistance with disposal, cleaning, and disinfection of the premises.

- Your property may be placed under surveillance, and nearby poultry keepers may be notified to heighten biosecurity.

In some cases, compensation may be available for euthanized birds if you’re part of the National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) or have registered your flock.

5. Investigation and Monitoring

USDA or state officials may:

- Track how the virus entered (wild birds, feed, new flock additions).

- Test nearby wild birds, commercial farms, or backyard flocks.

- Monitor surrounding areas for additional outbreaks.

6. Flock Reinstatement (if applicable)

Once the area is cleared and testing confirms that the premises are virus-free:

- You may be allowed to rebuild your flock, though restrictions may apply for a time.

- Biosecurity and surveillance continue for at least 30–90 days post-cleaning.

Why Reporting Matters

Reporting suspected AI cases:

- Helps stop the spread before it reaches more flocks, yours or others nearby.

- Triggers USDA support to contain and manage the situation.

- Protects commercial and backyard flocks from devastating outbreaks.

- Contributes to national surveillance data, which informs response strategies.

The Dilemma We Face as Pet Duck Owners

For those of us who keep ducks not just for eggs or pest control, but as beloved companions and cherished members of our family, the idea of reporting a potential case of avian influenza is deeply unsettling.

We’re told that if our ducks show signs of illness, especially during an outbreak, we should alert the USDA or our state’s animal health department. And on paper, it makes perfect sense. Reporting helps prevent the spread of the virus, protects other flocks, and triggers support systems that can contain the outbreak.

But the reality for pet duck keepers is much more complicated.

Our Ducks Are More Than Just Livestock

For most backyard or homestead duck keepers, these birds aren’t just poultry. They’re pets. They have names, personalities, favorite snacks, and morning routines. We celebrate their birthdays. We mourn them when they pass. They greet us at the door, follow us around the yard, and sleep tucked safely in the homes we built with our own hands.

So when we’re faced with the possibility that reporting a suspected illness could result in our entire flock being euthanized, the emotional stakes feel unbearable.

The Fear of Losing Healthy Ducks

One of the most difficult aspects of avian influenza in ducks is that they often survive the infection, especially domestic breeds like Muscovies or Pekins, and may not even show symptoms. Unlike chickens, which can die suddenly from HPAI, ducks may appear only mildly sick, or even recover completely on their own.

But once the virus is confirmed, even healthy-appearing ducks may be euthanized as part of the containment protocol. It’s a devastating thought: do we risk our entire flock being culled if one duck sneezes, or do we stay quiet and hope it’s just a cold?

Why Some Duck Keepers Don’t Report

Out of love and fear, some duck keepers may choose not to report suspicious symptoms. They clean more thoroughly, separate birds, monitor closely, and hope for the best. And while these actions are often done with the best intentions, they can unintentionally allow the virus to spread to wild birds, neighboring flocks, or even commercial farms.

This creates a painful moral tension: protect your ducks by keeping quiet, or risk losing them all by speaking up.

Balancing Compassion With Responsibility

There’s no easy answer here. But the more we talk about it, the more we can push for solutions that consider the unique needs of pet duck owners:

- Could there be testing-based surveillance, where only confirmed positives are culled, not entire flocks?

- Could individual bird isolation and treatment be allowed in non-commercial settings?

- Could we develop registration programs for pet flocks that offer an alternative pathway to mass depopulation?

Until then, many of us are left in a place of quiet worry, doing everything we can to keep our ducks safe and healthy, while knowing that one wrong call could change everything.

Prevention Is Still Our Best Tool

Because of this emotional weight, biosecurity becomes even more important. Preventing illness in the first place is the best way to avoid having to make this heartbreaking decision.

As duck lovers and keepers, we share a common goal: to protect the lives in our care while being mindful of the bigger picture. It’s not always easy, but it’s a conversation worth having.

Biosecurity: Your Best Line of Defense of Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

The good news? We’re not powerless against avian influenza. Whether you have two ducks or twenty, strong biosecurity practices are your best, and often only line of defense. While it’s easy to think of biosecurity as something only large farms worry about, it’s absolutely essential for backyard duck keepers, too.

By taking a few thoughtful steps, you can significantly reduce the risk of exposure to avian influenza and other infectious diseases.

Practical Biosecurity Measures for Backyard Duck Keepers

Let’s break it down into manageable actions you can start implementing today:

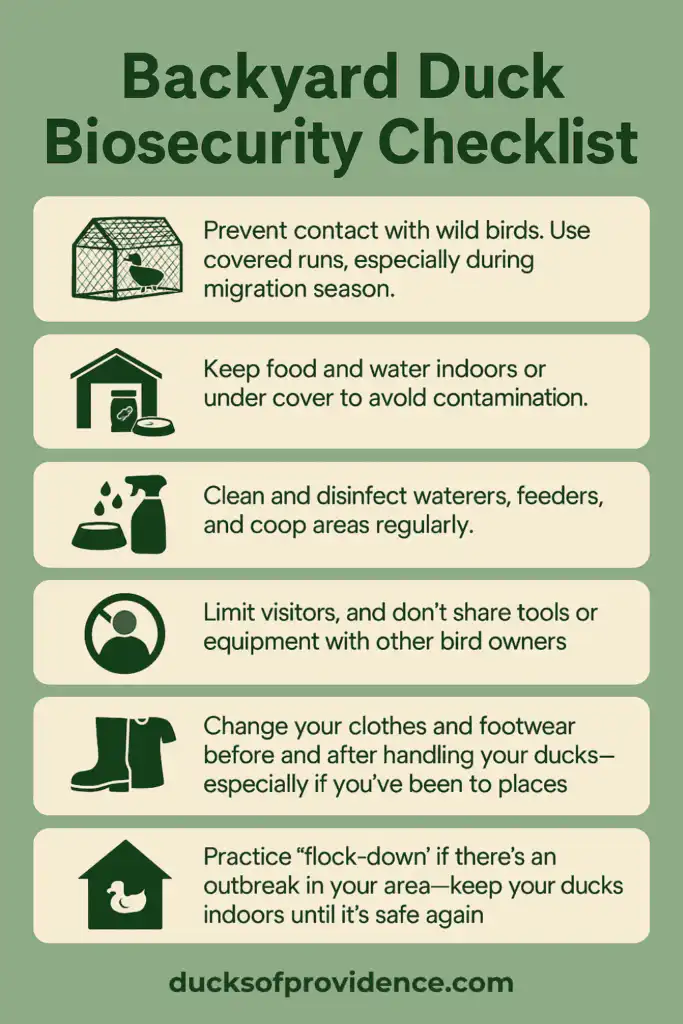

1. Prevent Contact with Wild Birds—Fully Cover the Run

Wild birds are the number one source of avian influenza. Simply using bird netting on top of the run is not enough. Droppings from overhead birds, especially migrating ducks, geese, and other waterfowl, can easily fall through mesh and contaminate your ducks’ space.

What to do instead:

- Use a solid roof or tightly woven tarp over your duck run to block droppings from wild birds flying overhead.

- Ensure side panels are enclosed as well, especially if wild birds frequent your yard or pond. Hardware cloth, plastic sheeting, or plexiglass panels are great for creating wind- and droplet-resistant barriers.

- If your ducks free-range in your backyard, consider transitioning to a secure covered run during peak migration or known outbreak seasons.

2. Feed and Water Under Cover

Feeders and water bowls left out in the open can become contaminated by droppings or feathers from visiting wild birds.

Better alternatives:

- Place feeders and water containers under a covered patio, awning, or inside the coop.

- Avoid using shared bird feeders or decorative ponds where wild birds might gather.

- If you have a pond, prevent your ducks from using it temporarily if wild birds are visiting.

3. Clean and Disinfect Regularly

Viruses like H5N1 can survive on surfaces for days, especially in damp or cool environments. That’s why regular cleaning routines matter more than ever.

Cleaning tips:

- Use a mild bleach solution (1 part bleach to 10 parts water) to disinfect feeders, waterers, and hard surfaces weekly or after potential exposure.

- Change bedding frequently, especially in nesting areas or water-heavy zones where bacteria can thrive.

- Spray down ramps and walkways with disinfectant, especially after wet weather.

4. Limit Visitors and Equipment Sharing

Even well-meaning friends or neighbors can bring pathogens with them, especially if they have birds of their own.

Play it safe by:

- Keeping your duck area off-limits to visitors during outbreak seasons or if you live in a high-risk zone.

- Avoid borrowing or lending feeders, tools, or housing structures between households with poultry.

- Set up a simple footbath with disinfectant at the entrance to your duck area and encourage its use before entering.

5. Change Clothes and Footwear

If you’ve visited a feed store, nature preserve, or a friend’s farm, or even walked through a parking lot where wild birds gather, you may unknowingly carry virus particles home on your shoes or clothing.

Best practice:

- Keep a dedicated pair of “duck boots” that never leave your property.

- Change into clean clothes before entering the duck area, especially after traveling, shopping for supplies, or visiting other animals.

- Wash your hands before and after handling your ducks, even if they appear healthy.

Know About Flockdown: It Might Be Mandatory

In some countries, especially the UK and parts of Europe, when avian influenza is detected in the region, the government may mandate a “flockdown.” This means:

- All poultry, including backyard flocks, must be kept indoors or in fully enclosed covered runs.

- Free-ranging is not permitted, regardless of whether you have a small backyard setup or a hobby farm.

- Enhanced biosecurity measures are required by law, including disinfection protocols and reporting.

While flockdown isn’t currently mandatory across the U.S., staying informed about local and national guidance can help you stay ahead of the curve and protect your ducks from risk.

Pro Tip: Keep a Biosecurity Checklist Near Your Coop

A laminated checklist with your daily and weekly biosecurity tasks can be a helpful reminder, especially for families with multiple caregivers. It’s also a great visual teaching tool for kids and visitors, so everyone’s on the same page when it comes to keeping your flock safe.

Monitor Outbreaks Near You

The USDA offers an excellent resource called the HPAI 2022–2025 Detections Map, which is regularly updated with confirmed outbreaks in both commercial and backyard flocks. You can find it here:

🔗 USDA APHIS HPAI Outbreak Map

Bookmark this page and check it periodically to stay informed, especially during migration seasons.

Ducks vs. Other Poultry: Are They Different?

Yes, ducks behave quite differently from chickens or turkeys when it comes to avian influenza:

- They’re more likely to be asymptomatic. Ducks can carry the virus and appear perfectly healthy, which can make containment tricky.

- They love water, a perfect environment for virus survival.

- They range farther, especially if free-roaming or kept near ponds, increasing exposure risks.

This means duck keepers need to be extra vigilant, even if your birds seem fine!

Can Humans Get Sick?

Human infections with avian influenza are rare but serious. So far, most cases have occurred through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments, not through eating properly cooked poultry or eggs.

The CDC and WHO consider the risk to the general public low, but those who work closely with birds, including backyard keepers, should take precautions like:

- Wearing gloves and masks during cleanup

- Washing hands thoroughly after contact

- Avoiding contact with sick or dead birds

If you develop flu-like symptoms after handling poultry, especially during an outbreak, seek medical advice and mention your exposure to birds.

Final Thoughts

As keepers of backyard ducks, we play a small but mighty role in safeguarding animal health. By staying informed, practicing good biosecurity, and keeping an eye out for symptoms, we can protect our flocks and help contain this virus.

Have you had to change your setup due to avian influenza concerns? Are your ducks showing any signs of illness? Share your experience in the comments or reach out. I always love hearing from fellow duck lovers.

Stay safe, and give your ducks a gentle quack from me!

Related Articles

- Understanding Avian Influenza (Bird Flu)

- 16 Common Duck Health Conditions You Should Know About

- 31 Must-have Items for Your Pet Duck First Aid Kit

- How to Conduct a Duck Health Check: A Comprehensive Guide

Deepen your understanding of avian wellness. Explore the full Duck Health & Anatomy Library for more specialized care guides.