Male and Female Duck Reproductive Systems

Last updated: February 28th, 2026

Ducks have one of the most fascinating and complex reproductive systems in the bird world. While most people are familiar with the eggs they lay, few realize just how intricate the internal processes are that make this possible. Understanding the reproductive anatomy of both male and female ducks not only deepens our appreciation for these remarkable birds but also helps us recognize and support their health throughout the seasons.

As a duck keeper and scientist, I’ve learned that knowing how your ducks’ bodies function, from the inside out, can make all the difference when it comes to egg production, breeding behavior, and even spotting potential health issues early. In this post, we’ll take a closer look at the reproductive organs of both hens and drakes, how they work, and what makes ducks truly unique among birds.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

Part of the Duck Health & Anatomy Hub, Evidence-based medical resources and anatomical research.

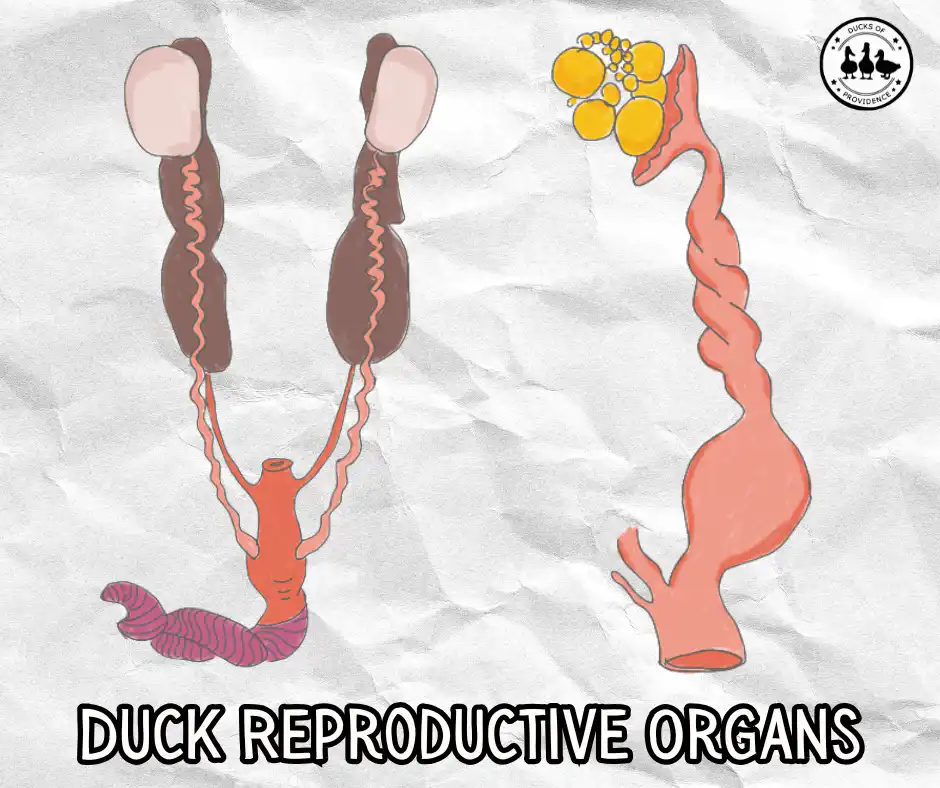

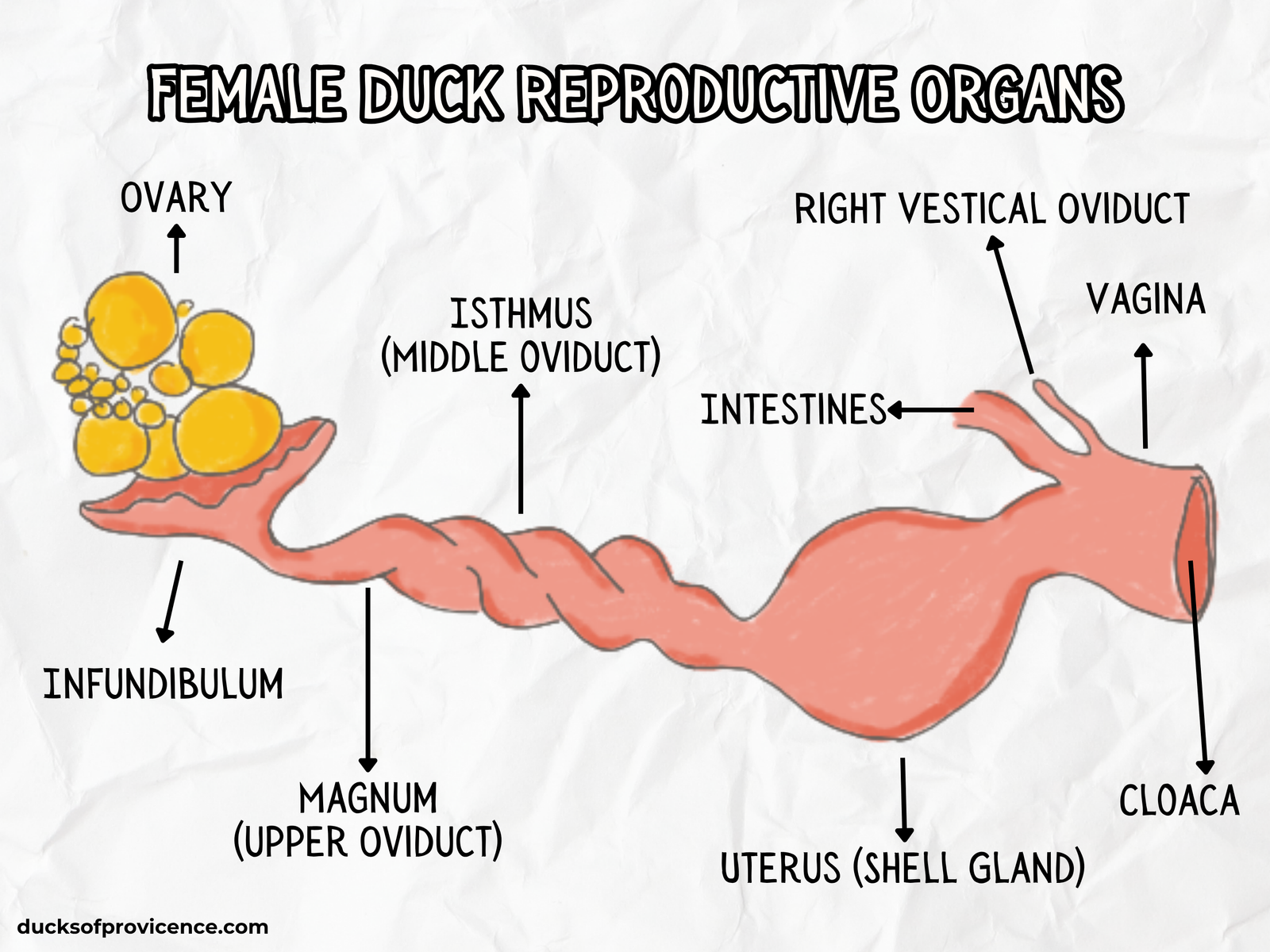

The Female Duck Reproductive System

A female duck’s reproductive system is a masterpiece of biological efficiency. Like most birds, she has only one functional ovary and oviduct, both located on the left side of her body. This adaptation reduces weight for flight, though even non-flying domestic ducks retain the same structure.

The Ovary

At the top of the system sits the ovary, which looks a bit like a cluster of tiny grapes. Each “grape” is a developing yolk, or ovum. The largest one at any given time will soon be released during ovulation. The yolks form in response to hormones such as estrogen and luteinizing hormone (LH), which are influenced by light exposure. This is why ducks often lay more eggs in spring and summer when daylight hours are longer.

Inside the ovary, several yolks mature at different stages, which allows ducks to lay eggs almost daily during their peak laying season. Once a yolk matures, it’s released into the next part of the reproductive tract: the infundibulum.

The Infundibulum

The infundibulum is a funnel-shaped structure that captures the yolk when it’s released from the ovary. This is also the site of fertilization, if the duck has recently mated. Ducks can store viable sperm in small sacs called sperm storage tubules, located near the junction of the vagina and shell gland. This means one successful mating can fertilize eggs for up to two weeks afterward.

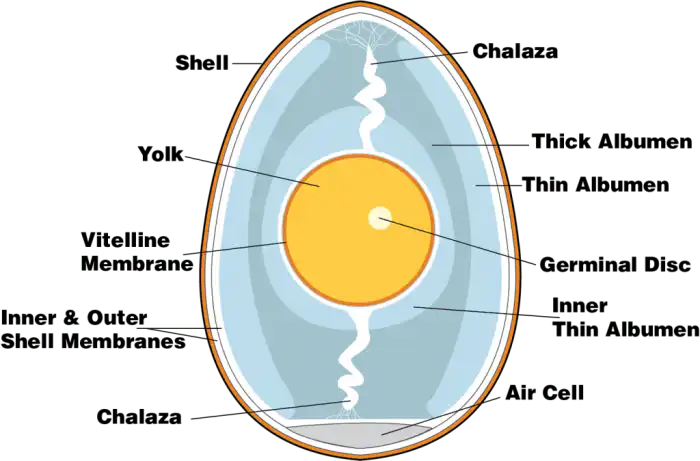

The Magnum

Next, the yolk moves into the magnum, a long section of the oviduct where the egg white (albumen) is added. This process takes about three hours, and the magnum’s glands secrete the proteins that make up the egg white. The albumen not only cushions and nourishes the developing embryo but also provides protection against bacteria.

The Isthmus

The isthmus is where the inner and outer shell membranes form. Thin but crucial layers that help regulate moisture and provide structure for the developing egg. The yolk and albumen spend about an hour in this section before continuing their journey.

4.271-274

The Uterus (Shell Gland)

The egg then enters the uterus, often referred to as the shell gland, where it spends the most time, typically 18 to 20 hours. Here, calcium carbonate from the duck’s diet (or from reserves stored in her bones) is deposited to create the hard shell. Pigment is added during this stage as well, giving duck eggs their range of colors from white to blue-green to charcoal gray, depending on the breed.

A calcium-deficient diet can lead to thin-shelled or soft eggs, which is why access to calcium sources such as oyster shell grit is essential for laying hens.

The Vagina and Cloaca

Finally, the fully formed egg enters the vagina, which leads to the cloaca, the shared exit for the digestive and reproductive tracts. During egg-laying, the oviduct everts slightly so the egg never touches fecal matter, helping to maintain cleanliness.

The entire journey from yolk release to egg-laying takes about 24 to 27 hours. Once an egg is laid, the next yolk is often already maturing in the ovary, continuing the cycle.

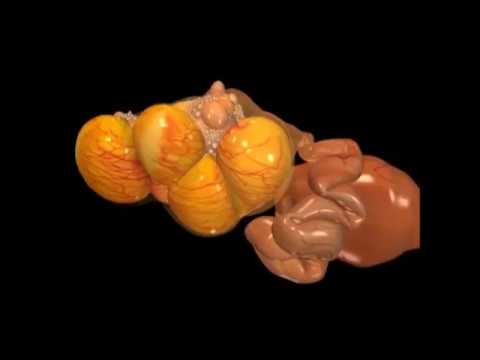

The following video nicely displays the process of egg development in chickens, which is very similar to that of ducks:

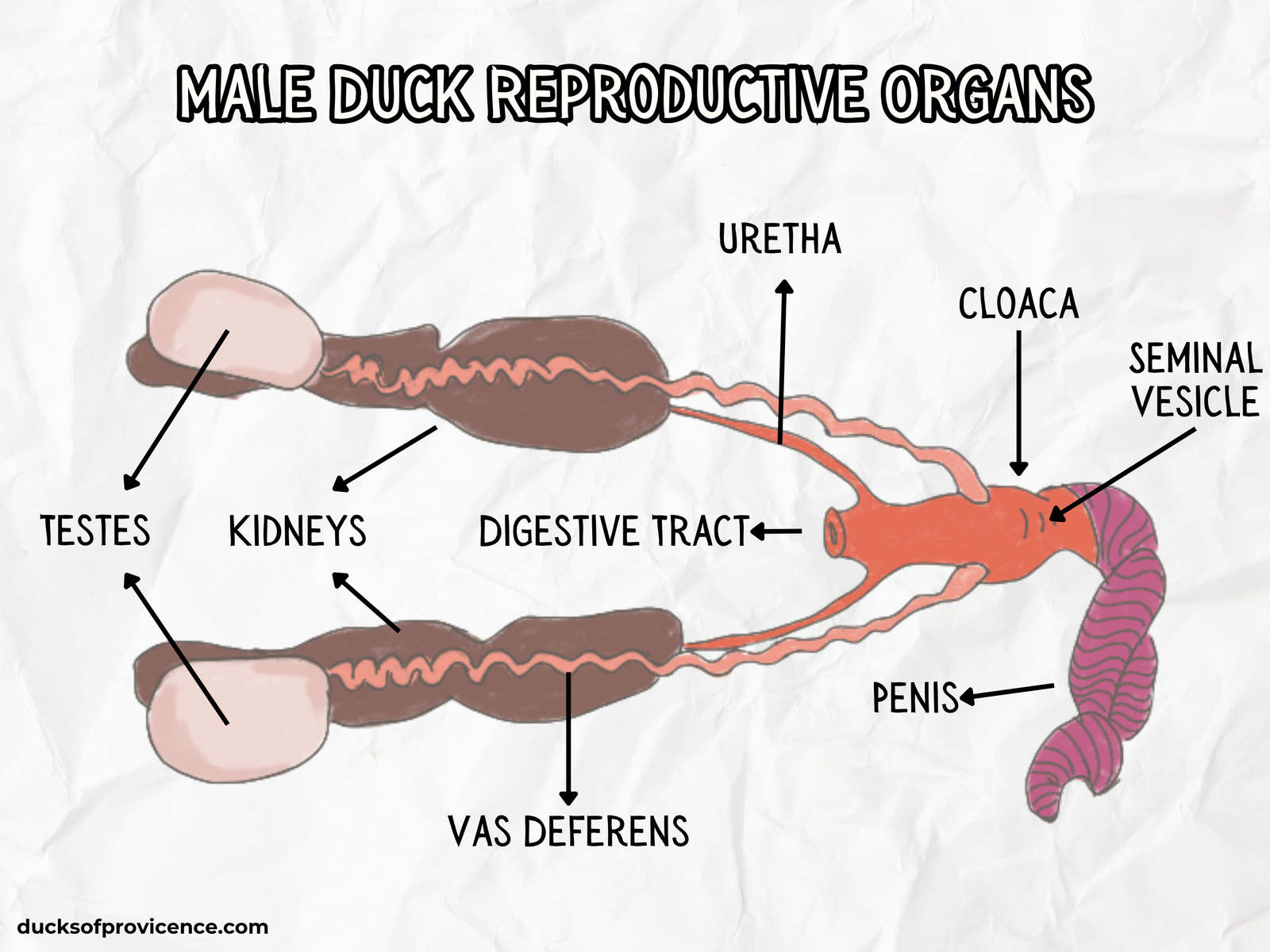

The Male Duck Reproductive System

The reproductive system of a male duck, or drake, is equally fascinating and unlike that of most other birds. While most male birds lack an external organ for copulation, ducks are among the few species that possess one. And it plays a major role in their reproductive success.

Internal Testes

Drakes have two internal testes, located deep within the body cavity near the kidneys. These organs are oval and pale in color, and they can expand dramatically during breeding season, sometimes up to 300 times their non-breeding size. This seasonal enlargement is controlled by hormones, particularly testosterone, which rises as daylight increases in spring.

The testes produce sperm and hormones, both essential for fertility and mating behavior. After the breeding season ends, hormone levels drop, and the testes shrink back to their resting size, conserving energy through the non-breeding months.

The Vas Deferens

From each testis runs a fine, coiled tube called the vas deferens, which carries sperm to the cloaca. These tubes join near the base of the cloaca, where sperm are stored until mating occurs. During this time, drakes may also display hormonal changes, such as increased preening, vocalization, or protective behavior toward their mate, all signs of active reproductive readiness.

The Phallus (Penis)

Unlike most birds, drakes have a phallus, a corkscrew-shaped organ made of lymphatic tissue rather than erectile tissue like in mammals. It remains coiled inside the cloaca when not in use and everts (unfolds outward) during copulation through hydraulic pressure from lymph fluid.

This organ is incredibly diverse across duck species. Some wild species have phalluses that are nearly as long as their entire body, while domestic breeds have shorter but still distinctive spirals. The shape and structure evolved alongside the complex female reproductive tract, creating what scientists describe as a coevolutionary “arms race.”

Female ducks have spiral-shaped vaginas that twist in the opposite direction of the drake’s phallus, along with blind pouches that can prevent unwanted fertilization. This gives females a degree of control over which matings lead to offspring, an extraordinary example of anatomical adaptation and evolutionary balance.

Cloaca and Copulation

Like females, drakes also have a cloaca, which serves as the common chamber for the digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems. During mating, the phallus everts from the cloaca and enters the female’s reproductive tract, transferring sperm into her oviduct. The entire process is very brief, often lasting just a few seconds.

Seasonal and Behavioral Changes

Drakes are most fertile during the spring and early summer months, when days are longest. Hormone-driven changes are visible even to duck keepers: brighter plumage, more frequent displays of head-bobbing or tail-wagging, and sometimes increased territorial or mating behavior.

As the breeding season ends, testosterone levels drop, the phallus regresses, and their focus shifts from breeding to molting and maintaining the flock hierarchy.

Anatomy Comparison at a Glance

| Feature | Drake (Male) | Duck (Female) |

| Primary Organs | Internal Testes | Left Ovary & Oviduct |

| External Signs | Sex feather (curly tail) | Loud “Honk” (usually) |

| Key Anatomy | Counter-clockwise phallus | Clockwise spiral oviduct |

| Function | Sperm production/delivery | Egg assembly & incubation |

Why Duck Reproductive Anatomy Is So Unique

Among birds, ducks stand out for their remarkably complex and specialized reproductive anatomy. What makes them so unique is not just the presence of organs like the drake’s corkscrew-shaped phallus or the female’s one-sided oviduct, it’s the way these structures evolved together over millions of years through a process called sexual coevolution.

The Evolutionary “Arms Race”

In many duck species, especially wild ones, mating can occur both by choice and by force. Over time, this has led to an extraordinary biological “arms race” between males and females. As male ducks evolved longer, more elaborate phalluses, females countered with reproductive tracts that twist in the opposite direction, creating spiral pathways and blind pockets that make it difficult for unwanted sperm to reach the egg.

This anatomical design gives females a degree of reproductive control, allowing them to favor sperm from chosen partners while still protecting against fertilization from forced matings. Scientists studying this phenomenon have found that the more coercive the mating system in a duck species, the more complex the female’s reproductive tract tends to be.

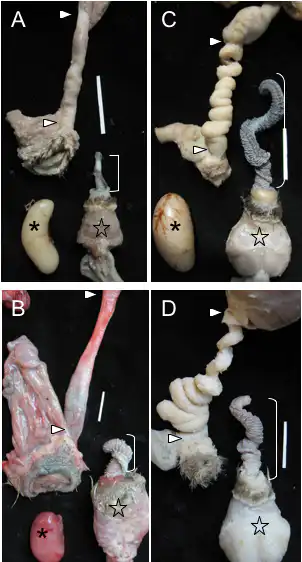

(A) Harlequin duck (Histrionicus histrionicus) and (B) African goose (Anser cygnoides), two species with a short phallus and no forced copulations, in which females have simple vaginas as in Fig 1a. (C) Long-tailed duck (Clangula hyemalis), and (D) Mallard Anas platyrhynchos two species with a long phallus and high levels of forced copulations, in which females have very elaborate vaginas (size bars = 2 cm). ] = Phallus, * = Testis, ★ = Muscular base of the male phallus, ▹ = upper and lower limits of the vagina.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000418.g002

Seasonal Changes and Adaptations

Another fascinating feature of duck reproduction is how seasonally dynamic it is. Both male and female reproductive organs shrink significantly outside of breeding season, conserving energy when reproduction isn’t a priority. As daylight increases in spring, hormones like testosterone and estrogen surge, signaling the body to regrow and reactivate these organs.

This seasonal cycle allows ducks to align their breeding with favorable environmental conditions. Ample food, warmth, and nesting opportunities, all of which improve the survival chances of their offspring.

Internal Fertilization and Egg-Laying Efficiency

Ducks have also perfected internal fertilization and efficient egg production. Their ability to store sperm means that a single successful mating can fertilize multiple eggs over several days or even weeks. This efficiency is especially important in the wild, where mating opportunities might be brief or unpredictable.

A Balance Between Biology and Behavior

Beyond anatomy, duck reproduction is also deeply behavioral. Courtship displays, synchronized head-bobbing, and vocal communication all play roles in mate selection and pair bonding. Many domestic ducks still display these behaviors, even when they don’t need to breed, showing how instinctive and ingrained these reproductive patterns are.

The unique reproductive anatomy of ducks is a testament to nature’s adaptability and creativity. Every twist of a spiral oviduct and every layer of an eggshell reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement, balancing survival, choice, and reproduction in ways that continue to captivate scientists and duck lovers alike.

Egg Production and Fertilization

Once a drake successfully mates with a hen, his sperm begins an incredible journey through her reproductive tract. Ducks have a highly specialized system that allows them to store and use sperm efficiently, ensuring multiple eggs can be fertilized from a single mating.

Fertilization

After copulation, sperm travels up the female’s oviduct and is stored in sperm storage tubules, small glands located near the junction of the vagina and uterus (shell gland). These microscopic structures can keep sperm alive for up to two weeks, sometimes even longer.

When the next yolk is released from the ovary into the infundibulum, the stored sperm swim upward to meet it. If they arrive in time, fertilization occurs in the infundibulum, before the albumen and shell layers are added. Once the sperm penetrates the yolk’s outer membrane, the embryo begins to form, even though its growth won’t start until incubation begins.

If no viable sperm are present, the yolk continues its journey unfertilized, resulting in an infertile egg. These eggs look identical to fertile ones from the outside and are perfectly safe to eat.

Egg Formation

After fertilization (or not), the yolk passes through several key stages as it transforms into a complete egg:

- Infundibulum (15–20 minutes): Captures the yolk and, if sperm are present, fertilization occurs here.

- Magnum (≈3 hours): Secretes albumen, or egg white, providing cushioning and protein for the embryo.

- Isthmus (≈1 hour): Adds the inner and outer shell membranes that separate the albumen from the shell.

- Uterus / Shell Gland (≈18–20 hours): Deposits calcium carbonate to form the hard shell and adds pigment for color.

- Vagina and Cloaca: The egg passes through these final sections for laying.

The entire process, from ovulation to egg-laying, takes about 24–27 hours. Ducks usually lay their eggs early in the morning, and if conditions are ideal, the next yolk is already developing when the previous egg is laid.

The Role of Light and Hormones

Day length is a major driver of egg production. Longer daylight hours stimulate the release of reproductive hormones such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which trigger ovulation and egg formation. That’s why most ducks naturally slow or stop laying in late fall and resume in spring unless provided with supplemental lighting.

Nutrition and Shell Formation

Producing an egg every day is an energy-intensive process. Calcium, protein, and vitamins (especially Vitamin D3) are essential for strong shells and consistent laying. Without enough calcium, ducks may produce thin-shelled or soft eggs, and prolonged deficiency can lead to depleted bone calcium and health problems.

I always keep a separate dish of oyster shell available for my laying hens so they can regulate their own intake. While my drakes and non-layers mostly ignore it, my females use it daily during laying season. A perfect example of how ducks naturally know what their bodies need.

Infertile vs. Fertile Eggs

For duck keepers, it’s helpful to understand the difference:

- Fertile eggs contain a small white ring called a blastoderm, visible when the egg is opened.

- Infertile eggs have only a tiny white spot, known as a blastodisc.

If eggs are collected daily and kept cool, both types are safe for consumption. Fertile eggs will not develop further unless they are incubated under the right temperature and humidity.

Health Considerations

Understanding the reproductive system is not just fascinating. It’s essential for keeping our ducks healthy. Many of the most common health problems in domestic ducks originate in the reproductive tract. Early recognition, proper nutrition, and veterinary support can make a significant difference in both prevention and recovery.

Common Issues in Females

Because domestic female ducks lay frequently, their reproductive systems are under constant demand. Over time, this can lead to complications such as:

- Egg Binding: When an egg gets stuck in the oviduct. Affected ducks may strain, appear lethargic, or sit fluffed up. Warm baths, calcium supplements, and veterinary care are often required.

- Prolapse (Cloacal or Oviduct): Occurs when part of the reproductive tract protrudes through the vent after laying. This can quickly become an emergency and requires immediate veterinary attention to prevent infection or tissue damage.

- Peritonitis (Egg Yolk Peritonitis): Happens when yolk material leaks into the abdominal cavity, often from a ruptured egg or reverse peristalsis. Signs include swelling, loss of appetite, and decreased activity.

- Ovarian or Oviductal Tumors and Cysts: Common in older or high-producing hens. You may notice progressive swelling of the abdomen or changes in laying patterns.

- Soft-Shelled or Shell-Less Eggs: Usually linked to calcium or Vitamin D3 deficiency, but may also occur due to stress or hormonal imbalance.

Providing adequate dietary calcium, access to sunlight or UVB exposure, and clean, fresh water for hydration helps reduce the risk of these issues. Ducks rely heavily on water for lubrication during laying, which is why it’s crucial they have access to deep water every day.

Common Issues in Males

While drakes have fewer reproductive problems, some health concerns can arise, especially during the breeding season:

- Penile Prolapse: The phallus fails to retract after mating, becoming swollen or exposed. It can lead to infection if not treated promptly.

- Injury or Infection: Overzealous mating, lack of swimming space, or dirty water can cause irritation or trauma to the phallus.

- Hormonal Aggression: Elevated testosterone during breeding season can make drakes territorial or rough with hens. Adjusting the male-to-female ratio and providing adequate space often helps.

Hormonal Imbalances

Domestic ducks that lay year-round, especially without natural breaks, can experience hormonal fatigue or reproductive inflammation. In some cases, veterinarians may recommend hormone implants such as Deslorelin acetate or Leuprolide acetate to pause egg production and allow the body to rest. These treatments have helped several of my own ducks recover from chronic reproductive strain.

Supporting Overall Reproductive Health

A healthy reproductive system starts with a healthy environment:

- Offer balanced nutrition formulated for laying ducks.

- Keep coops and runs clean and dry to prevent infections.

- Minimize stress from predators, crowding, or constant handling.

- Provide shaded resting areas and consistent access to water for swimming and bathing.

- Monitor behavior closely. Subtle changes in posture, appetite, or activity often signal early trouble.

Regular observation is the duck keeper’s greatest diagnostic tool. When you know what “normal” looks like for each of your ducks, you’ll notice quickly when something seems off. Early veterinary care can make the difference between a quick recovery and a serious condition.

Fun Facts About Duck Reproduction

- One-Sided Wonder: Female ducks have only one working ovary, the left one. The right ovary and oviduct stop developing before hatching.

- Speedy Process: It takes roughly 24 to 27 hours for a duck to form and lay an egg from start to finish.

- Sperm Storage Experts: Female ducks can store viable sperm for up to two weeks, meaning several eggs can be fertilized long after mating.

- Built for Control: The female’s oviduct spirals in the opposite direction of the male’s phallus, giving her more control over fertilization.

- Ever-Changing Organs: Both male and female reproductive organs shrink dramatically outside the breeding season to conserve energy.

- Hormones and Daylight: Increasing daylight triggers hormonal changes that restart egg-laying and mating behaviors each spring.

- The Drakes’ Display: During breeding season, drakes’ testicles can grow hundreds of times larger than they are in winter.

- Fertile or Not? You can tell a fertile egg from an infertile one by the tiny white spot on the yolk: a blastoderm indicates fertility, while a blastodisc means the egg is unfertilized.

- No Contact with Waste: During egg-laying, a duck’s oviduct everts slightly so the egg never touches fecal matter, an ingenious natural hygiene mechanism.

- Shell Strength: The color of a duck egg’s shell doesn’t affect its nutrition, but it does tell you something about the breed. Cayugas, for instance, lay stunning charcoal-gray eggs.

Duck Reproductive Anatomy: Frequently Asked Questions

How is duck anatomy different from other birds?

Most bird species (about 97%) do not have external genitalia; they reproduce via a “cloacal kiss.” Ducks are a rare exception. Male ducks (drakes) possess an internal phallus that everts during mating. This anatomical trait is linked to their aquatic environment, ensuring successful fertilization in the water.

What is the “corkscrew” anatomy I’ve heard about?

Ducks have evolved a fascinating “evolutionary arms race.”

The Male: The drake’s phallus is shaped like a counter-clockwise corkscrew.

The Female: The female’s oviduct is shaped like a clockwise corkscrew and contains “dead-end” pockets. This complex biological structure allows the female to have more control over which mating encounters result in fertilization.

Does a drake have testes like a mammal?

Yes, but they are located internally. A drake has two bean-shaped testes located near the kidneys, deep within the body cavity. These can expand significantly in size during the peak of the breeding season due to hormonal shifts.

How does the female produce an egg?

The female reproductive system consists primarily of the ovary (usually only the left one is functional) and the oviduct. The process is a biological assembly line:

Infundibulum: Where fertilization occurs.

Magnum: Where the egg white (albumin) is added.

Isthmus: Where the shell membranes are formed.

Uterus (Shell Gland): Where the hard calcium shell and pigments are added.

Vagina/Cloaca: The final exit point.

What are the signs of “over-mating” in a flock?

In a backyard setting, it’s important to monitor the male-to-female ratio. Signs that your females may be stressed or over-mated include:

Feather Loss: Specifically on the back of the neck or the base of the wings.

Lameness: Difficulty walking due to the weight or frequency of the male mounting.

Vents/Cloaca Irritation: Redness or swelling in the female’s vent area.

Can a female duck lay eggs without a male?

Yes. Just like a chicken, a female duck will ovulate and lay eggs based on light cycles and hormonal maturity. These eggs are unfertilized and will never hatch into ducklings. A drake is only necessary if you intend to hatch offspring.

Final Thoughts

The reproductive system of ducks is one of nature’s most intricate designs. An elegant balance between biology, behavior, and evolution. From the single ovary that produces each perfect egg to the drake’s remarkable seasonal changes, every detail has a purpose.

For those of us who care for pet ducks, understanding these systems is more than scientific curiosity. it’s a way to support their health and well-being. Knowing how and why our ducks lay, mate, and rest helps us recognize when something isn’t right and ensures we provide the best possible care through every stage of their lives.

Each egg laid is a small wonder, the result of finely tuned processes happening quietly within our ducks every day. By appreciating this complexity, we not only become better keepers but also deepen our connection to these incredible birds who share their lives and their hearts with us.

Related Articles

- Reproductive Issues in Ducks: What They Are, Why They Happen, and How to Help

- The Science Behind Duck Egg Laying Process: From Ovulation to Oviposition

- Breaking Down Egg Binding in Ducks: What Every Duck Keeper Should Know

- Soft-Shelled Eggs in Ducks – Everything You Need to Know

- No Eggs from Your Ducks? Discover 7 Reasons Why

- Prolapsed Phallus (Penis) in Pet Ducks

- Prolapsed Vent in Ducks: Causes, Treatment, and Prevention

Deepen your understanding of avian wellness. Explore the full Duck Health & Anatomy Library for more specialized care guides.

References

- Unraveling the Mysteries of Duck Mating (Yale Scientific)

- Brennan PL, Prum RO, McCracken KG, Sorenson MD, Wilson RE, Birkhead TR. Coevolution of male and female genital morphology in waterfowl. PLoS One. 2007 May 2;2(5):e418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000418.

- Brennan Patricia L. R.,Clark Christopher J. and Prum Richard O. 2010 Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia Proc. R. Soc. B.2771309–1314

- Comparative anatomical study on infundibulum of Pati and Chara-Chemballi ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus) during laying periods – Anil Deka, Gajen Baishya, Kabita Sarma and Manjyoti BhuyanVeterinary World, 7(4): 271-274