The Science of Duck Preening: Feather Care, Oil Glands, and Health

Last updated on September 21st, 2025 at 07:23 pm

If you watch ducks closely, you will notice that they spend a good part of their day grooming their feathers. This behavior is called preening, and it is far more important than simple tidying up.

Preening keeps feathers waterproof, aligned, and free from dirt or parasites. It also allows ducks to spread protective oils from a small gland near the base of the tail, which helps them stay buoyant in water and insulated against changing weather. Without preening, a duck’s feathers lose their protective function, which can lead to problems such as wet feather and even serious health issues.

For anyone keeping ducks as pets, learning about preening is more than a matter of curiosity. It is one of the best ways to understand your ducks’ daily routines and to recognize signs of both health and potential problems. In this article, we will explore how preening works, what role the preen gland plays, and how you can support your ducks in keeping their feathers in excellent condition.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

What Is Preening?

Preening is the act of feather maintenance. Ducks use their bills like a comb, carefully working through their feathers to keep them clean, smooth, and properly aligned. During this process, they also collect a small amount of oil from their preen gland, which they spread across their plumage.

For ducks, preening is not just grooming. It is an essential behavior that protects them from the elements, helps regulate body temperature, and keeps their feathers in working order for swimming and flying. A well-preened duck looks sleek, stays waterproof, and feels comfortable.

You will often see your ducks pause during the day to preen, especially after swimming or splashing in water. Preening is usually followed by a shake of the body or a stretch of the wings, which helps settle the feathers back into place.

The Role of The Preen Gland

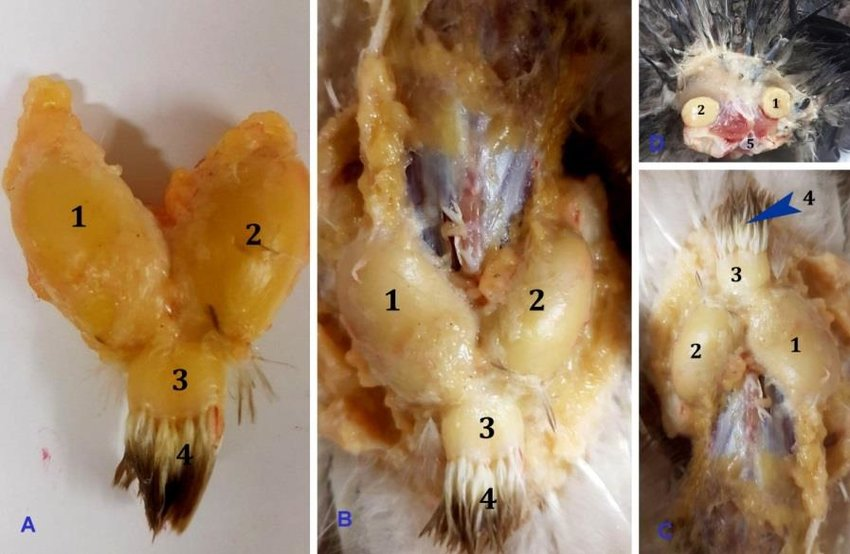

At the base of a duck’s tail sits a small but essential structure called the uropygial gland, more commonly known as the preen gland. This gland produces an oily secretion that ducks spread over their feathers while preening. Although the gland itself looks like a tiny bump covered with a tuft of feathers, it is the source of a duck’s waterproofing system.

The oil contains a mix of fatty acids, wax esters, and other compounds that serve several purposes. First, they create a hydrophobic coating that keeps water from soaking into the feathers. Instead of becoming heavy and waterlogged, the feathers repel water, allowing droplets to bead up and roll away. This coating is vital for maintaining buoyancy and insulation while swimming.

The preen oil also supports feather flexibility and durability. Feathers are made of keratin, the same protein found in human hair and nails, and they can become brittle without conditioning. By regularly spreading oil with their bills, ducks keep their feathers supple and aligned, which improves both flight and insulation.

Another benefit of the preen gland is its role in hygiene. Some studies suggest that the secretion has antimicrobial properties, reducing the growth of feather-damaging bacteria and fungi. Healthy preening not only keeps a duck’s plumage functional but also helps protect against infections that could compromise feather quality.

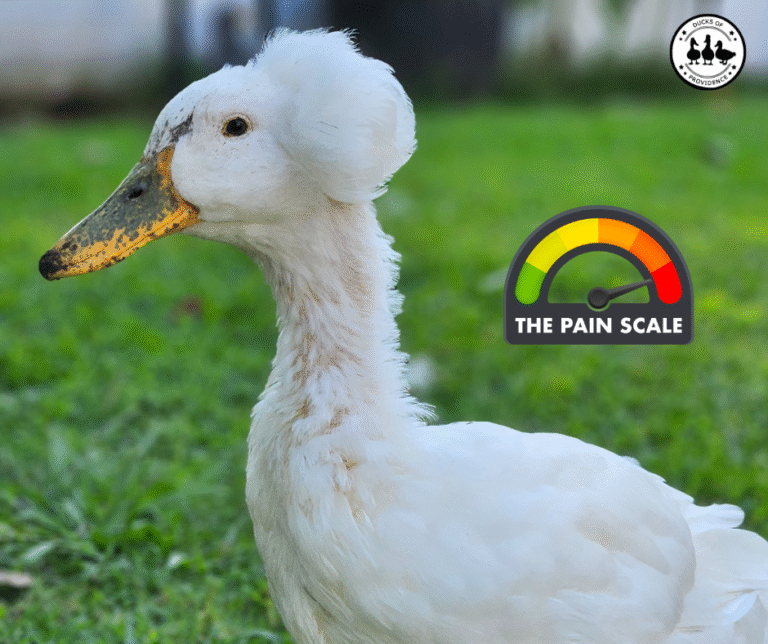

For ducks that cannot access their preen gland properly, such as certain Call Ducks with very short necks, feather condition can decline quickly. Without oiling, they are more vulnerable to wet feather, feather breakage, and chilling in cooler weather. This shows just how essential the preen gland is to overall health.

How Ducks Preen

Preening is a highly coordinated behavior that combines physical dexterity with feather biology. Feathers are complex structures made of keratin, with a central shaft (rachis) and hundreds of small barbs branching out from it. Each barb carries microscopic hooks called barbules that interlock like tiny zippers. When a duck preens, it uses the edges of its bill to realign these barbs and barbules, restoring the smooth surface that is essential for waterproofing and insulation.

The process begins when the duck bends its neck toward the base of its tail to press the bill against the preen gland. By squeezing the gland gently, the duck collects a small amount of oil on its bill. It then works through the feathers one by one, distributing this oil across the plumage. This oil is hydrophobic, meaning it repels water, and it prevents feathers from becoming saturated. At the same time, the duck may nibble along the shaft of the feather to remove dirt, broken bits of keratin, or small external parasites.

Preening also helps maintain feather flexibility. Keratin can become brittle without conditioning, and the combination of natural oils and mechanical alignment keeps feathers supple and durable. Ducks often accompany preening with vigorous shaking or wing flapping, which helps settle the feathers and spread oil more evenly.

The behavior is partly instinctive and partly learned. Ducklings begin to preen within their first few days of life, often imitating the motions of adults. However, the preen gland itself does not reach full function until several weeks of age, which means young ducklings practice the motions before they can actually distribute oil.

Because preening is linked so closely to feather structure, any disruption in preening behavior can quickly affect a duck’s health. Feathers that are not properly aligned lose their insulating properties, and without oiling they lose their ability to repel water. This is why observing how your ducks preen is one of the most useful ways to monitor their well-being.

Did You Know? The Science Behind Preening

Preening is not only about appearance, it also connects to fascinating biological processes that go deeper than most duck keepers realize.

Vitamin D Connection

The oil secreted by the preen gland is more than just a waterproofing substance. It contains precursors of vitamin D, which can be converted into active vitamin D when exposed to sunlight. As ducks spread the oil across their feathers and then spend time outdoors, sunlight activates these compounds on the feather surface. When the ducks later ingest the oil during additional preening, they may absorb vitamin D in its usable form. This link highlights how preening contributes indirectly to calcium balance and bone health, particularly important for laying ducks that require extra calcium for eggshell formation.

Chemical Variation in Preen Oil

Studies have shown that the chemical composition of preen oil varies not only between duck species but also between sexes and across different seasons. Males and females may produce slightly different oil profiles, and these differences can change during the breeding season. Scientists believe that these variations may play a role in communication and mate choice, with scent and chemical cues possibly helping ducks recognize individuals or assess reproductive readiness.

Feather Microstructure and Physics

The effectiveness of preening lies in the remarkable structure of feathers. Each feather is made of keratin and consists of a central shaft with barbs branching out, each covered with tiny barbules that hook together like microscopic zippers. When aligned properly, these structures create a smooth, interlocking surface that repels water and traps insulating air. Preening restores this alignment whenever daily activities disturb it. Without preening, the “zipper” effect weakens, water seeps in, and the insulating air layer is lost, leaving ducks at risk of chilling or sinking.

Taken together, these scientific insights show that preening is not only a visible grooming behavior but also a process deeply tied to physiology, feather biology, and even communication.

Why Ducks Preen

Preening serves several vital purposes that go far beyond simple grooming. Each time a duck runs its bill through its feathers, it is carrying out a process that protects its body and supports its overall health.

Waterproofing and Buoyancy

One of the most important reasons ducks preen is to keep their feathers waterproof. The oil they collect from the preen gland coats the feathers with a hydrophobic layer that prevents water from soaking through. Instead of getting waterlogged, droplets roll off the plumage and leave the down feathers beneath completely dry. This not only keeps the duck comfortable, but it also maintains buoyancy in the water. A duck with poorly maintained feathers has to work harder to stay afloat and is more vulnerable to chilling. In cases where waterproofing fails, ducks develop wet feather, a condition that compromises their health and requires quick attention from the keeper.

Insulation and Temperature Regulation

Feathers do more than protect ducks from getting wet, they also provide insulation. Properly aligned and oiled feathers trap small pockets of air close to the skin, forming a layer of insulation that helps ducks maintain body temperature in both hot and cold conditions. This air layer is what allows ducks to swim in icy water without losing too much body heat. When feathers are disturbed, this insulating blanket is disrupted. Preening restores it, ensuring that the duck can adapt to seasonal and daily changes in weather.

Feather Maintenance

Feathers are highly specialized structures that must remain intact to function properly. Each feather is made up of barbs and microscopic barbules that hook together like a zipper. Through preening, ducks carefully realign these structures, repairing tiny separations that occur during normal activity. This maintenance is essential for flying breeds, which depend on strong, smooth feathers for flight. However, even heavy domestic breeds that cannot fly need well-kept feathers for warmth, waterproofing, and protection from injury. Without regular preening, feathers become frayed, dull, and less effective.

Hygiene and Parasite Control

Preening also serves as a natural cleaning process. By working through their feathers, ducks remove dirt, dust, and loose down that could otherwise accumulate. They also dislodge small parasites, such as lice or mites, that can hide between the feathers. Some studies suggest that the oil from the preen gland may have antimicrobial or antifungal properties, which would give ducks additional protection against feather-degrading microbes. This means preening not only maintains feather structure but also supports overall hygiene.

Comfort and Stress Relief

Preening is more than just physical upkeep, it is also a soothing behavior. Ducks often preen during quiet, relaxed moments, and the repetitive motion appears to calm them. Access to clean water for bathing and preening contributes directly to their emotional well-being. Ducks that preen regularly tend to be more content and display fewer stress-related behaviors. Socially, preening can strengthen flock bonds. When ducks preen side by side or engage in allopreening, where one bird gently grooms another’s head or neck, it reflects trust and companionship.

What Healthy Preening Looks Like

A duck that preens regularly is usually in good health. Normal preening includes:

- Bending the neck to reach different parts of the body, especially the tail region.

- Running the bill along feathers to smooth and realign them.

- Pausing to touch the preen gland, then continuing to work oil across the plumage.

- A vigorous shake, wing stretch, or fluffing of the feathers at the end.

Preening often happens after swimming or bathing, but ducks also preen throughout the day as part of their regular routine. In a healthy flock, you will see ducks preening calmly and methodically, sometimes even together in a relaxed group setting.

What Healthy Preening Looks Like

A duck that preens regularly is usually in good health. Normal preening includes:

- Bending the neck to reach different parts of the body, especially the tail region.

- Running the bill along feathers to smooth and realign them.

- Pausing to touch the preen gland, then continuing to work oil across the plumage.

- A vigorous shake, wing stretch, or fluffing of the feathers at the end.

Preening often happens after swimming or bathing, but ducks also preen throughout the day as part of their regular routine. In a healthy flock, you will see ducks preening calmly and methodically, sometimes even together in a relaxed group setting.Title for This Block

Preening in Daily Duck Life

After Bathing and Swimming

Ducks are naturally drawn to water, and every splash, dive, or dunk serves an important purpose. Bathing loosens dirt, dust, and external parasites while also fluffing and ruffling the feathers. However, this activity temporarily disrupts the neat alignment of the feather barbs and can wash away some of the protective oil coating. Preening immediately after ensures that feathers return to their optimal condition.

A post-bath preening session usually begins with vigorous head shaking and wing flapping to shed excess water. The duck then bends its neck toward the preen gland, gathers oil on its bill, and methodically spreads it across the feathers. Each feather is gently nibbled and zipped back into place, restoring the microscopic hooks that allow barbs and barbules to interlock like Velcro. This action recreates the smooth, water-repellent surface that allows droplets to bead up and roll away.

The process may look repetitive, but it is highly efficient. By the time a duck finishes preening after a swim, its plumage is realigned, oiled, and ready for the next dive. This cycle of bathing followed by preening is crucial because it not only maintains feather health but also keeps ducks comfortable, buoyant, and insulated in the water.

Preening and Rest

Preening often accompanies moments of rest. Ducks may find a quiet, safe place, settle onto the ground, and spend several minutes grooming before tucking their heads under their wings for a nap. This sequence is more than just routine, it helps them relax.

By smoothing feathers and restoring their structure before sleep, ducks ensure that their insulating layer of down will function properly while they rest. This is especially important during cooler nights when body heat conservation is critical. For pet duck keepers, seeing a duck preen and then rest comfortably is a reassuring sign of both physical health and emotional security.

The Social Side of Preening

Preening is not always a solitary behavior. Ducks often preen together, especially when they feel safe and relaxed. This synchronized activity is a sign of flock harmony, with each duck grooming itself while staying close to others. Sometimes, ducks will even preen one another, a behavior called allopreening. This usually happens between bonded pairs or close companions and serves to strengthen social bonds. Ducks cannot easily reach every part of their bodies, so allopreening also helps with hard-to-reach feathers.

Watching a group of ducks preening side by side is more than just endearing. It reflects both physical health and emotional well-being. Ducks that do not feel secure are less likely to preen, so frequent group preening is a sign that your flock feels comfortable in its environment.

Preening in Ducklings

Ducklings begin practicing preening motions within the first week of life, even though their preen gland is not yet functional. They imitate the movements of adult ducks, bending their necks and nibbling at their tiny feathers. This early practice is essential, since preening is a learned behavior that must be mastered for survival.

The preen gland starts producing oil a few weeks after hatching. Once it becomes active, ducklings quickly shift from practice to effective preening. This transition is critical, as it allows them to waterproof their feathers and spend more time in the water without risk of chilling. For duck keepers, observing this milestone is a reassuring sign of healthy development.

Seasonal Influences

Preening behavior intensifies during molting seasons, when ducks shed old feathers and grow new ones. Molting leaves feathers uneven and often itchy, so ducks spend extra time preening to dislodge loose feathers and align the new growth.

During these periods, preening may appear more frantic or prolonged than usual. Ducks may also look temporarily ragged, since new feathers are still encased in keratin sheaths that must be broken open through preening. Although the process can look messy, it is entirely natural and necessary for the renewal of the plumage.

When Preening Signals a Problem

Preening is usually a sign of a healthy, well-adjusted duck. However, changes in the way a duck preens can provide early warnings of underlying issues. Careful observation of this daily behavior helps duck keepers catch problems before they become serious.

Lack of Preening

Ducks that stop preening altogether are often unwell. Illness, pain, or weakness may leave them without the energy to maintain their feathers. A duck that looks fluffed up, avoids swimming, or neglects grooming for extended periods is likely experiencing more than simple fatigue. Possible causes include infections, nutritional deficiencies, or injuries that limit movement. In these cases, a lack of preening is an important signal to investigate further and consider veterinary care.

Excessive or Repetitive Preening

While preening is normal, too much of it can indicate a problem. Ducks may focus obsessively on one area if they are dealing with external parasites such as mites or lice, or if dirty water has irritated their skin. Constant preening in the same spot can lead to broken or missing feathers. In some situations, stress alone may cause repetitive preening behaviors, much like nervous grooming in other animals. If a duck’s preening seems restless, destructive, or never-ending, it is time to check for environmental or health issues.

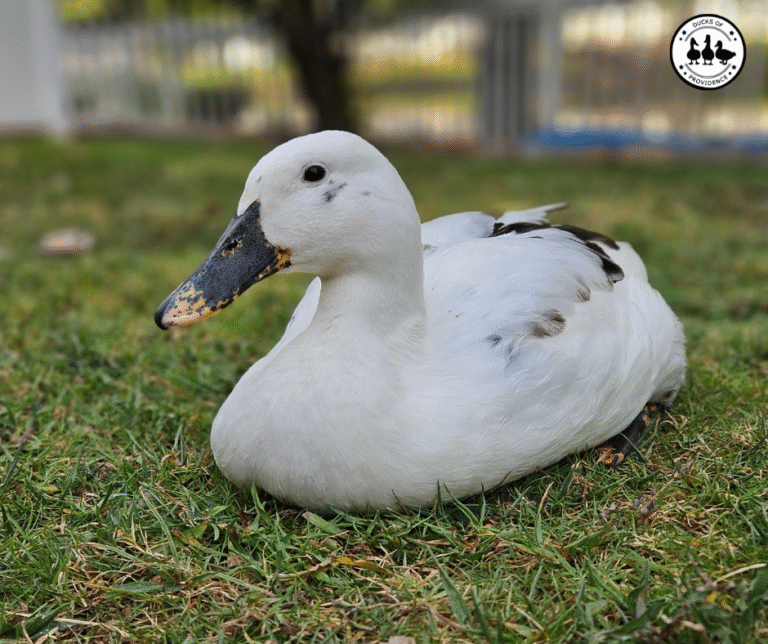

Wet Feather

One of the most concerning results of poor preening or preen gland issues is wet feather. In this condition, the feathers lose their waterproofing ability, allowing water to soak through to the down layer. Instead of rolling off, droplets cling to the plumage and leave the duck soggy even after shaking. Wet feather is dangerous because it destroys the insulating air layer that keeps ducks warm, leaving them vulnerable to chilling or hypothermia.

Wet feather can develop for several reasons:

- A malfunctioning, blocked, or infected preen gland.

- Contaminated or oily water that coats the feathers.

- Feather damage during molting or from poor nutrition.

- Inability to reach the gland, which is more common in short-necked breeds like Call Ducks.

Because wet feather can become life-threatening, it requires prompt action, such as improving water quality, checking nutrition, and in some cases, seeking veterinary care.

Visible Feather Damage

Healthy preening keeps feathers smooth, glossy, and well-aligned. If preening fails to achieve this, you may notice broken shafts, fraying, bald patches, or an overall dull appearance. These signs often point to underlying problems such as parasites, imbalanced diet, or feather chewing from stress. Since feathers are critical for warmth, waterproofing, and protection, visible damage should never be ignored.

Behavioral Changes During Preening

Ducks should appear calm and focused while preening. If the behavior looks restless or uncomfortable, with repeated stopping, wing flapping, or avoidance of water, there may be irritation or pain. Environmental problems like dirty water or contaminated bedding can play a role, but gland issues or skin infections may also be involved.

Breed-Specific Challenges

Certain breeds face extra difficulty with preening. Very small-bodied or short-necked ducks, such as Call Ducks, sometimes cannot reach their preen gland effectively. Without easy access to oiling, they are more prone to wet feather and feather breakage. Owners of these breeds must provide exceptionally clean bathing water and monitor feather condition closely.

By learning what normal preening looks like, you can recognize these red flags before they escalate. Addressing them early—through better nutrition, clean water, or veterinary support—helps prevent small problems from turning into serious threats to your duck’s health..

How Duck Keepers Can Help

Since preening is so vital, duck keepers can take several steps to encourage and support it:

- Provide Access to Clean Water

Ducks need water deep enough to dip their entire bill. This allows them to collect oil and wash away debris before preening. Pools or ponds give them the chance to splash, which ruffles the feathers and stimulates the need to groom afterward. - Maintain a Clean Environment

Dirty water or muddy runs can damage feathers and reduce the effectiveness of preening. Keeping pools refreshed and housing areas clean reduces the load of dirt and bacteria that ducks must manage with their bills. - Offer a Balanced Diet

Feather quality depends on good nutrition. Diets rich in protein, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential vitamins help feathers grow strong and flexible, which makes preening more effective. Deficiencies, especially in niacin or certain amino acids, can lead to weak or brittle feathers. - Monitor for Health Issues

Check your ducks regularly for signs of wet feather, parasites, or over-preening. If you notice changes in feather condition or behavior, it may be a sign that your duck needs veterinary care. - Consider Breed Limitations

Certain breeds, like Call Ducks, may have difficulty reaching their preen gland. Owners of these ducks should be extra mindful of feather health and may need to provide more frequent opportunities for bathing and careful observation of their condition.

By creating the right conditions, you make it easier for your ducks to carry out this instinctive but essential routine. A well-preened duck is not only more beautiful to look at, but also healthier, happier, and better protected against the elements.

Fun Facts About Preening

- Ducklings Practice Before It Counts

Ducklings start making preening motions within days of hatching, long before their preen gland is active. They are essentially rehearsing, copying the behavior of adults until the gland begins producing oil a few weeks later. - Preening Keeps Ducks Waterproof Even in Storms

Thanks to their oil and feather alignment, a well-preened duck can swim in heavy rain or icy water without getting soaked. Water beads up on the surface of their feathers just like it does on a freshly waxed car. - The Shake-and-Stretch Finale

Preening almost always ends with a big shake, a flap of the wings, or a dramatic stretch. This helps distribute oil evenly and ensures the feathers settle back into place. - Not Just for Looks

Shiny, well-kept feathers are not only attractive but also healthier. Glossy plumage reflects light differently than damaged feathers, which can make a preened duck stand out to potential mates in wild species. - Allopreening Shows Affection

When ducks preen each other’s head and neck feathers, they are not only helping with hard-to-reach spots but also strengthening their bond. This is especially common in bonded pairs or close companions. - The Gland Smells Different in Different Species

Research shows that the chemical makeup of preen oil varies between duck species. Some scientists believe this may play a role in mate choice or even in species recognition.

Caring for Ducks Through Preening Awareness

Preening is much more than a grooming habit. It is a vital behavior that keeps ducks waterproof, warm, and healthy. By maintaining feather alignment, distributing protective oils, and removing dirt or parasites, preening protects ducks from challenges both in and out of the water.

For duck keepers, watching a flock preen is more than just endearing. It is one of the best indicators of overall health and well-being. Ducks that preen regularly are usually comfortable and thriving, while ducks that stop or struggle with preening often need closer attention and care.

By providing clean water, good nutrition, and a safe environment, you allow your ducks to carry out this essential behavior as nature intended. In return, you will be rewarded with the sight of sleek, glossy feathers and a flock that is both healthy and content.

Relevant Articles

- The Science Behind Duck Feathers: Anatomy, Function & Care

- Why Wet Feather in Ducks Happens and How to Fix It

- Duck Anatomy: A Complete Guide for Pet Owners

References

- Mohamed, R. Macro and Microanatomical Study on the Uropygial Gland of the Mule Duck, Inter J Vet Sci, 2019, 8(2): 96-100.

- Jacob, J., & Ziswiler, V. (1982). The Uropygial Gland. In D.S. Farner, J.R. King, & K.C. Parkes (Eds.), Avian Biology (Vol. 6, pp. 199–324). Academic Press.

- Lucas, A.M., & Stettenheim, P.R. (1972). Avian Anatomy: Integument. U.S. Department of Agriculture. (Classic reference on feather structure, barbs, and barbules).