Mallard Ducks: From Wild Ancestors to Backyard Companions

Last updated on January 21st, 2026 at 09:34 am

Mallard Ducks are among the most recognizable and widespread ducks in the world, and for many, the first species that comes to mind when they think of a “classic duck.” But beyond their familiar green-headed appearance lies a fascinating history and an important role in the world of domestic duck breeds. In fact, almost every domestic duck (except the Muscovy) can trace its ancestry back to the wild Mallard.

Whether you’re spotting them at a pond, wondering if you can raise them as pets, or simply curious about their natural behaviors, this guide will walk you through everything you need to know about Mallard Ducks. From their origins and traits to legal considerations, egg-laying habits, and what it’s like to care for them at home, we’ll help you decide if a Mallard is the right fit for your flock.

Ducks of Providence is free, thanks to reader support! Ads and affiliate links help us cover costs—if you shop through our links, we may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks for helping keep our content free and our ducks happy! 🦆 Learn more

Part of the Beginner’s Handbook, Essential foundational data for new duck parents.

General Traits Table

| Trait | Description |

|---|---|

| Species | Anas platyrhynchos (wild-type, ancestor of most domestic duck breeds) |

| Weight | 2.5–3.0 lbs (drake), 2.0–2.5 lbs (hen) |

| Coloring | Males: green head, gray body, brown chest; Females: mottled brown |

| Speculum | Iridescent blue with white borders (both sexes) |

| Bill Color | Males: yellow; Females: orange with black markings |

| Feet/Legs | Bright orange |

| Flight Ability | Strong fliers, capable of long-distance migration |

| Size | Small to medium, sleek and lightweight |

| Distinguishing Features | Drake feather, iridescent speculum, strong contrast in male coloration |

| Eclipse Molt | Yes: drakes molt into female-like plumage in late summer |

History and Origin of Mallards

The Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is one of the most iconic duck species in the world, and for good reason. Native to the temperate and subtropical regions of North America, Europe, and Asia, Mallards are incredibly adaptable and have established themselves in a wide range of habitats, from remote wetlands to suburban ponds and city parks.

What many people don’t realize is that Mallards are the original blueprint for most of the ducks we know today. Nearly all domestic duck breeds, except for the Muscovy, are descendants of wild Mallards. Through thousands of years of selective breeding, humans have shaped Mallards into the heavier, flightless, and more docile ducks we now keep for eggs, meat, or companionship. Breeds like the Pekin, Khaki Campbell,Indian Runner, and Cayuga all share Mallard ancestry, even if their appearance and behavior have diverged dramatically.

Domestication likely began in parts of Asia over 2,000 years ago and gradually spread to other regions. Mallards were favored not only for their egg-laying ability but also for their calm disposition, which made them easier to manage in human care. Yet despite this long history of domestication, wild Mallards still thrive in nature, and their influence continues through both deliberate crossbreeding and natural interbreeding with escaped domestic ducks.

Because Mallards can interbreed with nearly all domestic breeds (again, excluding Muscovies, which are a separate species), they play a unique role in shaping the genetic diversity of both wild and domestic duck populations. This ability to hybridize has also led to increased concern in some regions about preserving the genetic integrity of wild populations.

Today, Mallards are a familiar sight throughout much of the world. Whether flying in formation overhead, dabbling in a backyard pond, or nesting in an urban flower bed, these ducks remain an enduring symbol of adaptability, resilience, and the close relationship between humans and waterfowl.

Appearance of Mallard Ducks

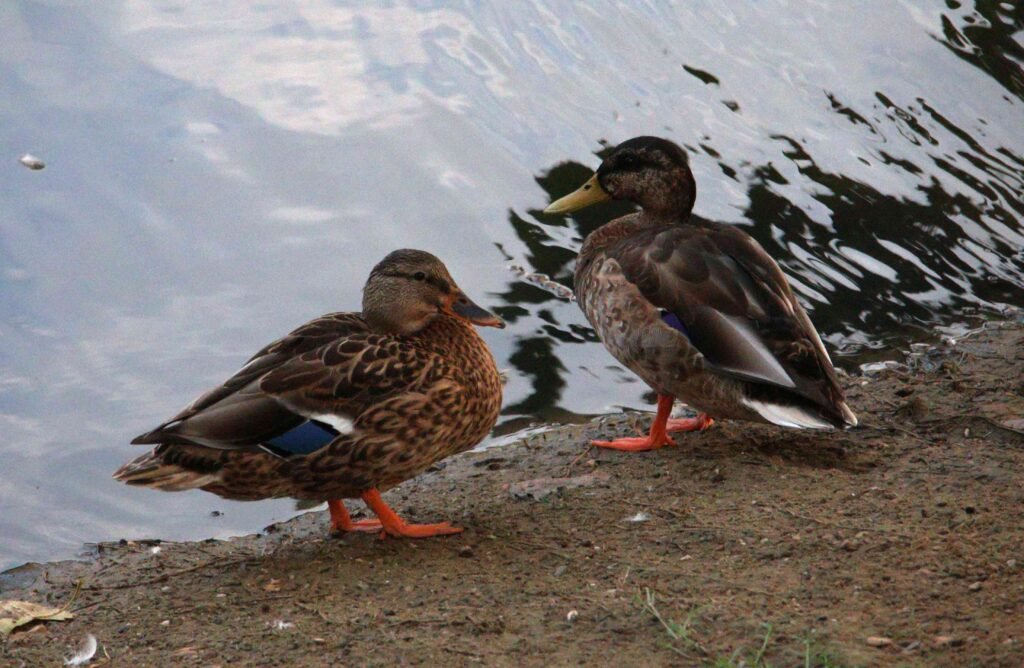

Mallards have a classic duck shape, with a rounded body, medium-length neck, and a slightly upturned tail. Their appearance is sexually dimorphic, meaning males and females look distinctly different.

The drake (male) is especially eye-catching, with a glossy green head, a white ring around the neck, a chestnut-brown breast, and a grayish body. His curled central tail feathers (known as the drake feather) and iridescent speculum, the bold blue patch on the wing, make him instantly recognizable.

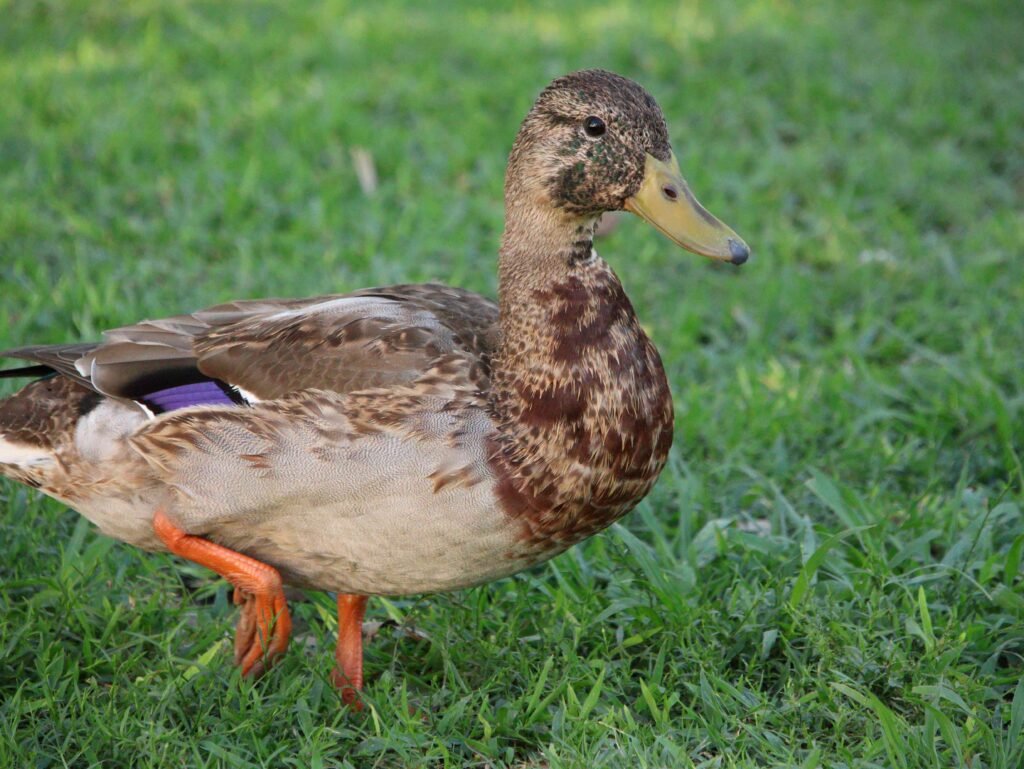

The hen (female) has a more camouflaged look, with warm mottled brown plumage and an orange-and-black bill. This coloring helps her blend in when nesting. Despite her more muted tones, the iridescent blue speculum is still present and bordered by white, just like in the drake.

Both sexes have bright orange legs and webbed feet. Mallards weigh less than most domestic breeds, which contributes to their ability to fly well, a key difference that sets them apart from their heavier, farm-raised descendants.

During the eclipse molt, drakes lose their colorful breeding plumage and look more like females for a few weeks in late summer, helping them stay hidden while their flight feathers regrow.

Natural Behavior and Temperament of Mallards

Mallards are alert, active, and incredibly adaptable birds. As wild ducks, they retain strong instincts that shape their behavior, even when raised in captivity. Compared to domestic breeds, Mallards tend to be more cautious and independent, especially if not hand-raised from a young age.

In the wild, Mallards are dabblers. They feed by tipping forward in shallow water to forage for aquatic plants, insects, larvae, seeds, and small invertebrates. On land, they’ll graze on grass and grain or scavenge for food near humans. Their varied diet reflects their highly opportunistic nature.

Mallards are also excellent flyers. Their lightweight build and strong wing muscles allow them to take off vertically and cover long distances. Wild populations migrate seasonally, with northern birds flying south in the winter and returning to breed in the spring. In contrast, captive Mallards may not migrate but often retain the physical ability to do so if not pinioned.

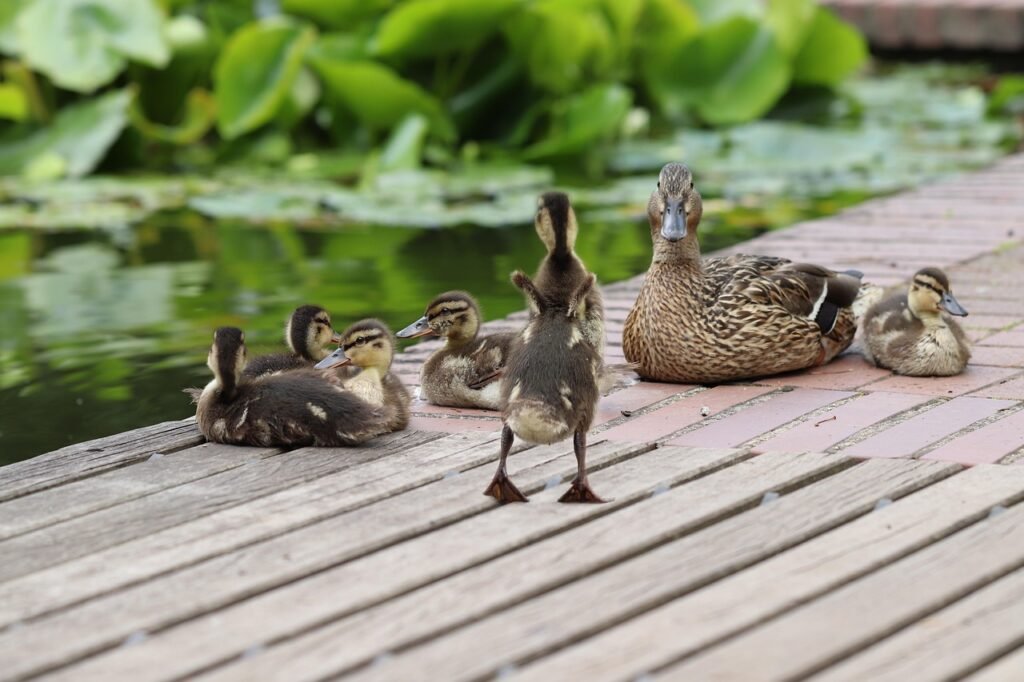

They are social animals and often gather in flocks, especially outside the breeding season. In spring, pairs form, often with intense competition among drakes, and hens build nests close to water sources. Mallard hens are attentive mothers and will fiercely protect their ducklings, which imprint on their mothers within hours of hatching.

In a backyard or aviary setting, Mallards are typically more flighty and wary than domestic ducks. However, with patience and consistent interaction, they can become quite calm and even bonded to their caretakers, especially if raised from hatchlings.

Mallards as Pets

Keeping Mallards as pets can be deeply rewarding, but it’s important to understand that these are wild-type ducks, not fully domesticated birds. Their behavior, care needs, and even legal status are different from typical backyard breeds like Pekins or Runners.

Legal Considerations

Because Mallards are a native wild species in North America, owning them often requires special permits or licenses, depending on your location. In the United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service regulates the possession of wild ducks under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Even if Mallards are sold through hatcheries like Metzer Farms, they must be captive-bred and properly marked (usually by removal of a back toe or leg banding) to legally distinguish them from wild-caught birds.

Always check your state and local wildlife laws before acquiring Mallards. Some states require permits to keep them, others restrict ownership entirely, and a few allow them with documentation of captive origin. It’s also important to keep detailed records of where your ducks came from and retain any paperwork from the hatchery or seller.

Challenges of Keeping Mallards

Mallards are strong fliers, and unless they are pinioned (a permanent procedure to prevent flight) or kept in a fully enclosed aviary, they may escape, especially during the spring or fall when migratory instincts are strongest.

They’re also more skittish than domestic breeds. Even with daily interaction, they tend to stay cautious and are quick to startle. This doesn’t mean they can’t be social, especially if hand-raised from hatchlings, but it does require more patience and time to build trust.

Another challenge: Mallards are excellent brooders and mothers. If you keep a female Mallard, be prepared for seasonal nesting behavior. They may become very protective and territorial during this time.

Why People Love Them

Despite these considerations, many duck keepers are drawn to Mallards for their natural beauty, intelligence, and ancestral connection. Watching a bonded pair or a mother leading her ducklings around your pond can feel like a slice of wilderness in your own backyard. Their vivid coloring, natural behaviors, and strong instincts make them fascinating to observe.

If you’re willing to meet their needs and are legally allowed to keep them, Mallards can be an incredibly enriching addition to a pet flock. Just be sure to provide a secure environment, understand their wild traits, and commit to responsible ownership.

Egg Production and Reproduction

As the ancestors of nearly all domestic duck breeds, Mallards have retained many of their natural reproductive behaviors, including strong brooding instincts and seasonal laying patterns.

Egg Production

Mallard hens typically lay between 50 and 100 eggs per year, depending on their environment, diet, and whether they are in the wild or in captivity. This is considerably lower than prolific domestic breeds like Khaki Campbells or Welsh Harlequins, which can lay over 250 eggs annually.

Their eggs are generally off-white to pale green or blue, medium-sized, and have a slightly pointy shape compared to the rounder eggs of some heavier breeds. Egg production is seasonal, with most eggs laid in spring and early summer. In cooler climates or under natural lighting, hens will often stop laying entirely in fall and winter.

Captive Mallards may lay a bit more regularly than their wild counterparts, especially if provided with supplemental lighting and a high-quality diet. However, because they are not bred for high egg output, they are not typically chosen for egg-laying purposes.

Reproductive Behavior

Mallards are seasonal breeders, with pair bonds forming in late winter or early spring. Unlike many domestic ducks, which may form loose pairings or breed promiscuously, Mallards tend to form strong seasonal pairs. However, drakes can still become aggressive during the mating season, and competition for hens can lead to bullying if not managed carefully in captivity.

One of the most distinctive traits of Mallard hens is their strong brooding instinct. When given the chance, they will build a nest in a concealed area, lay a clutch of 8–13 eggs, and incubate them diligently for about 26–28 days. During this time, hens rarely leave the nest except to eat, drink, and bathe briefly.

After hatching, the ducklings are precocial, meaning they are born with down feathers, open eyes, and the ability to walk and swim almost immediately. The mother leads them to water soon after hatching and continues to protect and guide them for several weeks.

In captivity, Mallard reproduction can be both a joy and a challenge. Hens that go broody may stop laying for long periods, and ducklings need secure housing to protect them from predators, even in suburban areas.

Housing and Care Needs

Mallards may be small in size, but their care needs are unique, especially since they are still very close to their wild counterparts. Providing the right environment is essential to keeping them healthy, safe, and happy.

Space and Enclosure

Mallards are agile, lightweight ducks with strong flying abilities. Unlike domestic breeds that are often too heavy to fly well, Mallards can take off vertically and disappear over a fence if they are not safely contained.

If you plan to allow outdoor access, you’ll need:

- A fully enclosed aviary or predator-proof run with a covered roof.

- Fine, sturdy mesh (1/2” hardware cloth is ideal) to prevent escapes and keep out predators.

- A secure night shelter that is dry, draft-free, and locks shut to protect against raccoons, foxes, owls, and other threats.

Some keepers choose to pinion Mallards at a young age (a permanent surgical procedure performed by a licensed avian vet that removes part of one wing to prevent flight). This should only be done after serious ethical consideration.

An alternative is wing clipping, a temporary and non-surgical method that involves trimming the primary flight feathers on one wing to unbalance flight. This method should be repeated after each molt and is only recommended if you are comfortable identifying the correct feathers or have assistance from an experienced avian veterinarian or bird keeper.

For pet owners who want to preserve their Mallards’ natural abilities, a well-designed covered run or aviary remains the safest and most humane option.

Shelter and Nesting

Your duck house should provide at least 4–6 square feet per duck and be equipped with soft, absorbent bedding such as straw, pine shavings, or hemp. Mallards prefer quiet, tucked-away areas to nest, so include small nesting boxes or secluded corners within the house.

Make sure ventilation is excellent, but drafts are avoided, especially in winter. Clean bedding regularly to prevent respiratory issues and parasites.

Water and Foraging

Mallards thrive when they have access to naturalistic water sources. A shallow pond, kiddie pool, or large water trough gives them the opportunity to bathe, dabble, and forage, important for both their physical and behavioral health.

Like all ducks, they require water deep enough to submerge their heads to clean their nostrils and eyes. If you don’t have a pond, provide a clean water source that is changed daily.

They also benefit from natural foraging: allow them supervised time in a grassy area where they can search for bugs, seeds, and greens. Just make sure the area is fenced and safe from predators or escape.

Diet

A balanced diet is critical. Feed a high-quality waterfowl or duck-specific maintenance feed, supplemented with greens, grains, and occasional treats. Because Mallards are light-bodied and active, avoid feeds formulated for rapid weight gain (such as meat bird crumbles or broiler feed).

Always serve food in a dish or water pan deep enough to allow dabbling, which mimics their natural feeding behavior and helps prevent choking.

Hardiness and Health of Mallard Ducks

Mallards are hardy, resilient ducks that have adapted to survive in a wide range of environments. As a wild-type species, they retain many of the natural advantages that help them stay healthy in the wild, but pet owners should still be prepared to monitor their health closely and provide proper care.

Climate Tolerance

Mallards are highly adaptable to both hot and cold climates. In the wild, they range from the Arctic tundra to subtropical wetlands, and they overwinter in areas as warm as Central America. Their thick down and waterproof outer feathers give them excellent insulation in winter, while their small body size helps them manage heat better than heavier breeds.

That said, they still need an appropriate shelter:

- In winter, make sure they have a dry, draft-free coop with extra bedding to keep warm.

- In summer, provide ample shade, fresh water for swimming, and ventilation to help them stay cool.

Disease Resistance

Mallards are generally robust and less prone to certain health issues that affect overbred domestic ducks, such as reproductive disorders or leg deformities. However, they are still susceptible to:

- Parasites (worms, mites)

- Avian influenza and other respiratory diseases

- Bumblefoot (especially if kept on hard or rough surfaces)

- Metal or toxin ingestion from foraging in contaminated areas

Because of their natural foraging behavior, Mallards are more likely to eat things they shouldn’t if given free range, so it’s important to check their environment regularly for hazards like rusty metal, sharp plastics, or treated wood.

Health Monitoring

Mallards tend to mask signs of illness, a survival trait common in wild birds. This makes regular health checks especially important:

- Monitor weight and appetite weekly.

- Check for signs of lethargy, labored breathing, or changes in droppings.

- Inspect feet, eyes, nostrils, and vent area routinely.

- Observe behavior: if a normally active bird is isolating or not preening, it may be time to call a vet.

Mallards are also strong swimmers and require regular access to clean water for bathing. Keeping feathers in good condition is not just cosmetic. It’s essential for waterproofing and temperature regulation.

The Mallard: Ancestor of Domestic Duck Breeds

Nearly every domestic duck breed we know today, except for the Muscovy, can trace its genetic roots back to the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos). This wild species provided the foundation for thousands of years of selective breeding that gave rise to the diverse, colorful, and specialized duck breeds we now keep for eggs, meat, and companionship.

Origins of Domestication

Domestication of the Mallard likely began more than 2,000 years ago, with the earliest records pointing to Southeast Asia and China. People in these regions began raising tame Mallards for food and egg production, selectively choosing birds that were:

- less flighty and easier to manage,

- more tolerant of close human contact,

- better at laying eggs consistently,

- and eventually, larger and meatier in body size.

Over generations, these traits became fixed, and domesticated ducks began to diverge physically and behaviorally from their wild ancestors.

The process was gradual and influenced by geography, need, and cultural preference. For example:

- In Europe, Mallards were bred into heavier utility breeds like the Rouen and the Aylesbury.

- In Asia, more upright and lightweight breeds such as the Indian Runner were developed, prized for their egg-laying ability and foraging efficiency.

- In the U.S., selection led to the development of the American Pekin, which came from Chinese stock and is now the most widely raised meat duck breed in the country.

Genetic Connection and Hybridization

Domesticated Mallard-derived breeds belong to the same species, Anas platyrhynchos domesticus, and can freely interbreed with wild Mallards. This is why escaped domestic ducks can (and often do) mate with wild populations, creating hybrids that can be fertile and hard to distinguish from pure wild types.

This ongoing gene flow is both a strength and a concern:

- It has allowed for the development of new domestic varieties.

- But it also threatens the genetic purity of wild Mallards in some regions, especially where domestic ducks are released or escape into the wild.

Genetically, domestic ducks tend to have:

- A larger body size, due to selection for meat production.

- Reduced flight capability, especially in heavier breeds.

- Altered behavior, with reduced fear of humans and less seasonal migration drive.

- Modified egg production, particularly in breeds like the Khaki Campbell or Golden 300, which lay almost year-round.

Despite these differences, many physical traits, like the iconic iridescent speculum, orange feet, and overall feather pattern, still reflect their Mallard origins. Even domesticated breeds that look quite different, like the Cayuga or Silver Appleyard, share nearly all their DNA with wild Mallards.

Understanding Selective Breeding

Selective breeding is the process by which humans intentionally choose animals with specific traits to reproduce, gradually shaping a species over generations. In the case of Mallards, this process is how we ended up with the wide variety of domestic duck breeds we have today.

Here’s how it works:

- Observation and Selection

Duck keepers observe a group of ducks and identify individuals with desirable traits. For example, a hen that lays more eggs than others, a drake that is especially calm, or a duck with a larger body size for meat production. - Controlled Mating

Only the ducks with those desired traits are allowed to breed. Their offspring are then observed to see which of them inherit those same traits. - Repetition Over Generations

This selection and breeding process is repeated over many generations. Each time, breeders continue selecting for the traits they want, while avoiding those they don’t (like nervousness, poor egg production, or low disease resistance). - Fixing Traits in the Population

Over time, the traits become more common and eventually standard within the breed. After many generations, the new breed may look and behave quite differently from its wild ancestors, even though it’s still genetically very close.

For example:

- Mallards that laid more eggs were selected over time to create breeds like the Khaki Campbell, which lays over 300 eggs per year.

- Mallards with calmer temperaments and heavier bodies were chosen to develop breeds like the Pekin, which doesn’t fly and grows quickly for meat production.

- Mallards with upright posture and fast foraging behavior contributed to the Indian Runner Duck.

Selective breeding is not genetic modification. It doesn’t involve changing DNA in a lab. It relies entirely on natural genetic variation and careful breeding choices. When done responsibly, it can enhance useful traits while preserving the health and well-being of the animals.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mallard Ducks

Are Mallards legal to keep as pets?

It depends on your location. In the U.S., Mallards are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. You can legally own captive-bred Mallards if they are properly marked (toe clipped or banded), and in some states, you may need a permit. Always check with your state’s wildlife agency before acquiring Mallards.

Can Mallards live with domestic duck breeds?

Yes, but with care. Because of their smaller size and wilder nature, Mallards may be bullied by larger, heavier domestic breeds. They may also fly away if not properly contained, so secure housing is essential. Social compatibility can vary depending on the individual ducks and how they’re raised.

Do Mallards make good pets?

They can, especially if hand-raised from hatchlings. However, they are naturally more skittish and independent than domestic ducks. If you’re looking for a cuddly, easygoing pet, a breed like a Pekin or Welsh Harlequin may be a better choice. But for those who appreciate natural duck behavior, Mallards can be incredibly rewarding to keep.

Can Mallards fly?

Yes, very well. Mallards are excellent fliers and can easily escape over fences or fly long distances. If you want to keep them contained, you’ll need a covered run, or consider wing clipping (temporary) or pinioning (permanent, surgical).

How many eggs do Mallards lay?

Mallard hens usually lay 50–100 eggs per year, mostly in the spring. Their eggs are off-white to pale green or blue. They’re not prolific layers like Khaki Campbells or Runners, but are attentive mothers with strong brooding instincts.

Will Mallards migrate if I keep them outside?

Captive Mallards typically don’t migrate, especially if they’ve been hand-raised and have access to food and shelter. However, their migratory instincts can still be strong, especially in fall. Flight-capable Mallards may join wild flocks if not secured.

Are Mallards noisy?

Mallard hens can be quite vocal, especially during mating season or when calling their ducklings. Drakes are much quieter. Their quacks are less booming than a Pekin’s, but still distinct.

What do baby Mallards eat?

Ducklings should be fed a non-medicated, waterfowl-specific starter crumble with adequate niacin (vitamin B3) for healthy leg development. Always serve with plenty of water deep enough to dabble in, and avoid chick starter feed unless it’s supplemented with additional niacin.

Do Mallards need a pond?

While not required, they thrive with access to water for swimming, dabbling, and cleaning. A kiddie pool or shallow tub changed daily can meet their needs if a pond isn’t available.

How long do Mallards live?

In captivity, Mallards can live 8–12 years with proper care. In the wild, their lifespan is often shorter due to predators, disease, and environmental stress.

Final Thoughts

Mallard ducks are more than just beautiful. They’re a living link to the wild roots of almost every domestic duck breed. Whether you admire them for their natural behaviors, their vibrant plumage, or their remarkable adaptability, Mallards have a quiet charm that’s easy to fall in love with.

But keeping Mallards isn’t quite the same as keeping traditional pet ducks. Their ability to fly, their seasonal instincts, and their more cautious temperament mean they require a bit more planning, patience, and understanding. They’re not ideal for everyone, but for those willing to meet their needs and follow local regulations, Mallards can be a truly enriching addition to the backyard.

If you’re drawn to the idea of caring for a bird that still holds onto its wild heart, Mallards might just be the perfect fit. With proper housing, secure space, and a thoughtful approach, these graceful ducks can thrive in a home setting, bringing a little piece of nature right into your backyard.

Master the basics of evidence-based care. Explore the full Beginner’s Handbook to build a strong foundation for your flock.

Other Breeds

- Ultimate Duck Breed Comparison Guide: Find the Right Duck for Your Flock

- Cayuga Ducks: The Beautiful Black Duck Breed

- Ancona Duck – A Rare Duck Breed

- Muscovy Ducks: The Gentle Giants of the Duck World

- Welsh Harlequin Duck – Friendly, Hardy, and Stunningly Unique

- Khaki Campbell: The Champion Egg Layer That Can (Almost) Fly

- Crested Ducks: Pets with a Genetic Defect

- Indian Runner Ducks: The Upright, Active, and Entertaining Breed

- Pekin Ducks: The Classic Backyard Companion

- Silver Appleyard Ducks: The Beautiful Heavyweight Champions of Egg Production

- Swedish Ducks: Calm, Hardy, and Strikingly Beautiful

- Call Ducks: Tiny Ducks with Big Personalities

- Wood Ducks: North America’s Tree-Nesting, Wild Beauties

I have a question about some ducks I have . Not sure if they are rouens or mallards ❓How can I share some photos ❓

Absolutely, please send the picture to our email contact@ducksofprovidence.com