Exploring Duck Migration

Last updated on October 10th, 2024 at 07:41 pm

Duck migration is one of nature’s most fascinating phenomena, showcasing these waterfowl’s incredible endurance and instinct. Millions of ducks start on long journeys, traveling thousands of miles between their breeding and wintering grounds each year. But why do they migrate, how do they navigate such vast distances, and what challenges do they face along the way?

Why Ducks Migrate

The need for food and suitable breeding habitats primarily drives migration. In the northern hemisphere, many duck species breed in the spring and summer when food is abundant and the weather is warm. As the days grow shorter and temperatures drop, food sources like insects and aquatic plants become scarce, prompting ducks to migrate to warmer regions with more reliable food supplies. By moving to different areas seasonally, ducks can exploit the best conditions for feeding and raising their young.

Here’s a closer look at the key reasons behind this incredible journey:

1. Food Availability

One of the most compelling reasons ducks migrate is the food search. In temperate regions, the availability of food fluctuates dramatically with the seasons. During the spring and summer, wetlands, lakes, and rivers are full of life, providing abundant aquatic plants, insects, and small fish essential for ducks to feed themselves and their ducklings. However, these food sources become scarce as fall approaches and temperatures drop. Water bodies may freeze over, and vegetation dies back, making it difficult for ducks to find the nourishment they need to survive. Migration allows ducks to move to regions where food remains plentiful, such as warmer southern areas where the climate supports year-round food production.

2. Breeding and Raising Young

For many duck species, migration is closely tied to their reproductive cycle. The northern breeding grounds offer an optimal environment for nesting and raising ducklings. The long daylight hours of northern summers provide ample time for feeding, which is crucial for adult ducks and their growing offspring. These regions often have fewer predators and lower human activity, creating a safer environment for ducks to lay eggs and rear their young. By migrating northward in the spring, ducks can take advantage of these favorable conditions to ensure the next generation has the best possible start.

3. Climate and Weather Conditions

Ducks are highly sensitive to changes in weather and temperature. As the seasons change, they seek climates that match their physiological needs. During the colder months, many ducks migrate to milder climates, where they can avoid the harsh winter conditions of the north. These warmer regions provide more consistent food supplies and offer a more comfortable environment that reduces the energy needed to maintain body temperature. Migration allows ducks to inhabit areas that fit their seasonal needs, moving between climates as conditions change.

4. Avoiding Competition

Migration also helps ducks avoid competition for resources. During the summer breeding season, northern areas can support a high density of birds, including other waterfowl species. However, as food becomes scarce in the fall, staying in one place would lead to intense competition for the limited resources available. By migrating, ducks can reduce this competition by spreading out across different regions, ensuring that each bird has access to enough food and suitable habitats without overcrowding.

5. Historical and Evolutionary Factors

Over centuries, ducks have evolved migratory behaviors as a response to environmental pressures. These behaviors are deeply ingrained in their biology and passed down through generations. Migration routes and timing are often inherited, with young ducks following older, more experienced birds. This evolutionary adaptation has allowed ducks to thrive in various environments, from the icy tundra of the Arctic to the balmy wetlands of the tropics. The instinct to migrate is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of these birds, enabling them to survive and reproduce across vast and diverse landscapes.

How Ducks Navigate: Nature’s Built-In GPS

When it comes to migration, ducks are like seasoned travelers with a natural GPS system guiding them across thousands of miles. But how exactly do these birds find their way? The answer lies in a combination of instinct, environmental cues, and even some learned behaviors.

1. The Role of Instinct and Genetics

Ducks are born with an incredible sense of direction, hardwired into their brains. This instinctual knowledge results from evolution, with each generation inheriting the ability to navigate from their ancestors. This means that even young ducks making their first migration have a built-in understanding of where they need to go. They might not know the exact route, but they have a strong sense of the general direction they should be heading in. This genetic blueprint is like a map embedded in their DNA, guiding them on their journey.

2. Using the Sun and Stars

Ducks are skilled at using celestial cues to navigate. During the day, they rely on the position of the sun to determine direction. Just as old sailors used the sun to guide their ships, ducks can tell which way is north or south based on where the sun is in the sky. At night, they switch to using the stars. The North Star, in particular, serves as a crucial reference point for many species, helping them maintain their course even in the dark. This ability to read the sky is something they seem to know—no training required!

3. Sensing the Earth’s Magnetic Field

One of the most fascinating aspects of duck navigation is their ability to sense the Earth’s magnetic field. Inside their heads, ducks have specialized cells that contain tiny particles of magnetite, a mineral that responds to magnetic fields. This biological compass allows them to detect the direction and strength of the Earth’s magnetic field, which they use to orient themselves during migration. This internal compass works even when clouds obscure the sun or stars, ensuring ducks stay on track no matter the weather.

4. Landmarks and Environmental Features

While instinct and celestial cues play a significant role, ducks also rely on recognizable landmarks to help them navigate. Rivers, mountains, coastlines, and even man-made structures like highways can be visual guides. As ducks make the same journey year after year, they become familiar with these features, using them to confirm they’re on the right path. This familiarity can be especially important when approaching their breeding or wintering grounds, where precise navigation is crucial.

5. Learning and Social Cues

Migration isn’t just an individual effort—ducks often travel in flocks, and this social aspect plays a big role in navigation. Younger, inexperienced ducks learn from older, more experienced birds. Flying in formation with the group, they pick up on the best routes and stopover sites. This learned behavior is passed down through generations, creating a shared knowledge base that ensures the survival of the flock. It’s like having a group of seasoned travelers showing the way to newcomers.

6. Adjusting to Environmental Changes

Ducks are also highly adaptable and can adjust their routes based on environmental changes. For instance, if a traditional stopover site becomes unsuitable due to habitat loss, ducks may alter their path to find a new resting spot. This flexibility is crucial in today’s rapidly changing world, where human activities and shifting climates are constantly reshaping the landscapes ducks rely on.

Key Points of Duck Navigation

In short, ducks are equipped with an extraordinary set of tools that help them navigate across vast distances. Their ability to use the sun, stars, magnetic fields, and familiar landmarks, combined with their inherited instincts and learned experiences, makes them remarkable navigators. Understanding how ducks find their way home deepens our appreciation for these amazing birds and highlights the importance of preserving the natural environments they depend on.

Ever notice your own ducks showing signs of these navigation skills? It’s just one of the many fascinating aspects of their behavior!

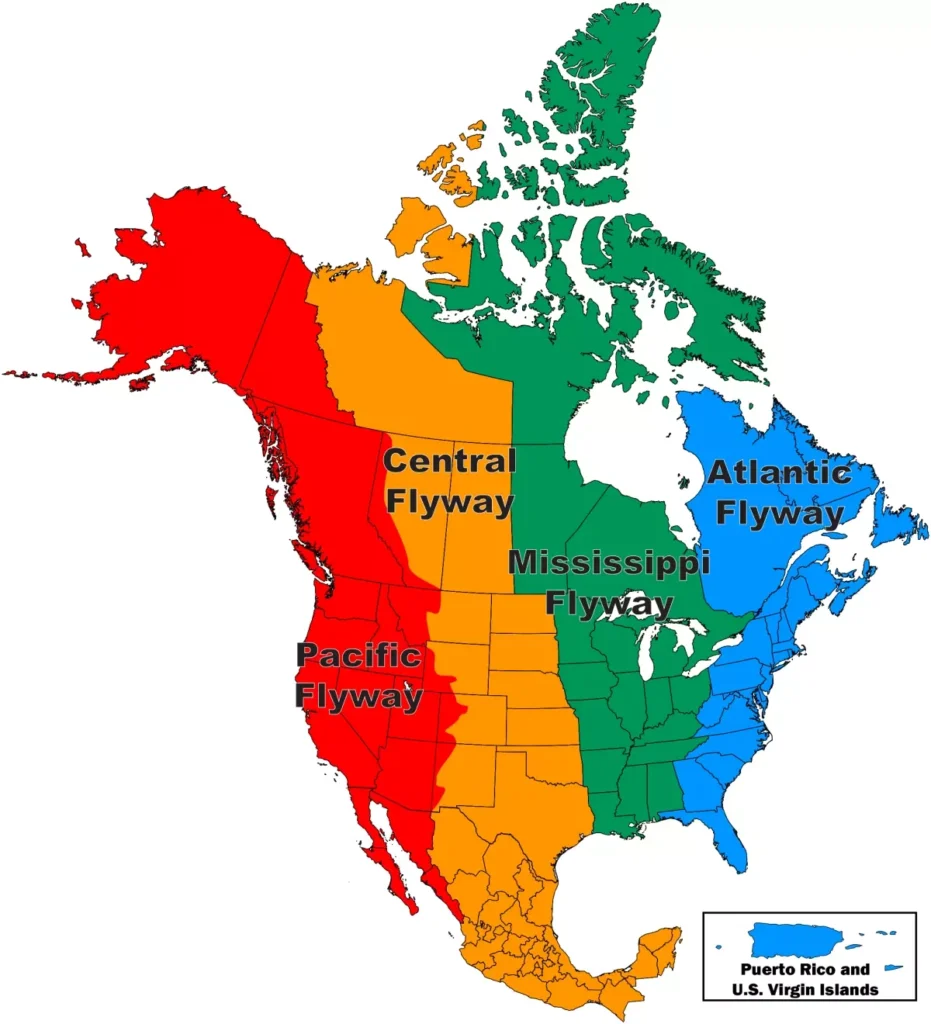

Major Duck Migration Routes: The Highways in the Sky

Ducks don’t just fly in random directions during migration; they follow well-established pathways known as flyways. These routes are like highways in the sky, guiding ducks across continents to their seasonal destinations. Each flyway is a network of critical habitats, including wetlands, rivers, and lakes, that provide rest and nourishment during these long journeys. Let’s explore the major flyways that ducks use in North America.

1. The Atlantic Flyway

The Atlantic Flyway runs along the eastern coast of North America, stretching from the Canadian Arctic all the way down to the Caribbean and South America. This route is used by a wide variety of duck species, including Black Ducks, Mallards, and American Wigeons. Along the way, ducks stop at key sites like the Chesapeake Bay, the Everglades, and coastal marshes. These areas offer rich feeding grounds where ducks can refuel on their journey. The Atlantic Flyway is particularly important because it passes through some of the most densely populated regions of the United States, making the conservation of wetlands in these areas crucial for the survival of migrating waterfowl.

2. The Mississippi Flyway

Known as the “superhighway” of duck migration, the Mississippi Flyway is the most heavily traveled route in North America. It follows the Mississippi River from its origins in the northern forests and wetlands of Canada down to the Gulf of Mexico. This flyway is a vital corridor for species like Northern Pintails, Gadwalls, and Wood Ducks. The river and its tributaries provide a continuous ribbon of wetland habitats, making it an ideal route for ducks. Along the way, they stop at famous locations like the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge and the Delta region, where they can rest and feed before continuing their journey. The Mississippi Flyway supports a massive number of ducks, making it a focal point for conservation efforts.

3. The Central Flyway

The Central Flyway covers a vast area, stretching from the tundra of Canada and Alaska through the Great Plains and down into Central and South America. This route is essential for ducks like the Northern Shoveler, Blue-winged Teal, and Redhead. The Central Flyway offers a mix of habitats, from prairie potholes and shallow lakes to expansive grasslands and wetlands. One of the key stopover points along this flyway is the Rainwater Basin in Nebraska, which provides critical feeding grounds for millions of migrating ducks each year. The diversity of habitats along the Central Flyway makes it a rich resource for ducks, but it also means that they face varying environmental challenges as they migrate.

4. The Pacific Flyway

The Pacific Flyway runs along the western coast of North America, from the Arctic tundra through the Rocky Mountains and down to Mexico and beyond. This flyway is home to species like the Northern Pintail, Green-winged Teal, and Cinnamon Teal. Key stopover sites include the Klamath Basin, California’s Central Valley, and the wetlands of the Salton Sea. The Pacific Flyway is unique in that it offers a wide range of habitats, from coastal estuaries to high mountain lakes, providing diverse feeding and resting opportunities for migrating ducks. However, the Pacific Flyway is also among the most threatened by habitat loss, particularly in California, where water management and agricultural expansion have significantly reduced wetland areas.

Summarizing Duck Flyways

The major migration routes followed by ducks are marvels of natural engineering, guiding these birds across continents and over vast distances. Understanding these flyways helps us appreciate the incredible journeys ducks undertake and highlights the importance of conserving the critical habitats that support their migrations. Every stopover site along these routes is a crucial link in the chain of survival for migrating ducks, making conservation efforts along these flyways vital for the future of waterfowl populations.

Have you ever seen large flocks of ducks passing overhead during migration? Knowing the flyways they follow can make spotting them even more exciting!

Importance of Flyways and Conservation Efforts for Duck Migration

Each flyway is a vital lifeline for migrating ducks, connecting breeding grounds in the north with wintering areas in the south. These routes are not just random paths; they have been shaped by centuries of duck migration patterns, with each generation following the routes that have proven successful for survival. The importance of these flyways cannot be overstated, as they ensure that ducks have access to the resources they need throughout their migration.

However, flyways are only as strong as the habitats they connect. Wetlands, rivers, and other stopover sites along these routes are essential for providing food and shelter, but many of these areas are under threat from human activities. Conservation efforts are crucial to protect and restore these habitats, ensuring that ducks can continue to migrate successfully. Organizations and governments work together to create protected areas, manage water resources, and raise awareness about the importance of these migration routes.

Challenges of Duck Migration: The Perils of the Journey

Migration is an incredible feat of endurance, but it’s not without its challenges. Ducks face numerous obstacles on their long journeys, from natural predators to human-made hazards. Understanding these challenges gives us a deeper appreciation for the resilience of these birds and underscores the importance of conservation efforts. Let’s explore some of the major challenges ducks encounter during migration.

1. Habitat Loss

One of the biggest challenges ducks face is the loss of critical habitats along their migration routes. Wetlands, which are essential for feeding and resting, have been disappearing at an alarming rate due to agriculture, urban development, and industrial activities. When these wetlands are drained or degraded, ducks lose the vital resources they need to survive their journey. For example, the Central Valley of California, once a vast wetland paradise, has been significantly reduced, leaving ducks with fewer options for stopovers. The loss of these habitats can force ducks to take longer, more exhausting routes, or leave them without enough energy to complete their migration.

2. Predation

While ducks are on the move, they are more vulnerable to predators. Birds of prey, such as hawks and eagles, often target migrating ducks, especially in areas where they are forced to stop and rest. On the ground, mammals like foxes and raccoons may also prey on exhausted or injured ducks. The risk of predation is higher during migration because ducks may be flying over unfamiliar territory, where they don’t know the safest places to land or hide. This constant threat adds to the physical and mental stress of migration.

3. Human-Made Hazards

Human activities have introduced a range of new dangers for migrating ducks. Power lines, wind turbines, and communication towers can all pose deadly obstacles in the sky. Collisions with these structures are a significant cause of mortality for many bird species during migration. Additionally, pollution from pesticides, oil spills, and industrial runoff can contaminate the water and food sources that ducks rely on along their routes. Hunting pressure is another challenge, especially in areas where ducks congregate in large numbers during migration. While regulated hunting can be sustainable, illegal or excessive hunting can significantly impact duck populations.

4. Disease

The crowded conditions at key stopover sites can sometimes lead to the spread of diseases among migrating ducks. Avian influenza, botulism, and duck viral enteritis are just a few of the diseases that can spread rapidly through flocks, especially when ducks are stressed and weakened from their journey. These diseases can lead to large die-offs, which not only threaten individual flocks but also have broader implications for duck populations across their entire migration range.

5. Energy Depletion

Migration is an energy-intensive process, and ducks need to carefully manage their energy reserves to make it to their destination. If they encounter unexpected challenges, such as strong headwinds, extreme cold, or a lack of food along the way, they can quickly become exhausted. Energy depletion can lead to reduced fitness, making ducks more susceptible to disease, predation, and other risks. This is why stopover sites with abundant food are so critical—they allow ducks to replenish their energy stores and continue their journey.

6. Navigational Disruptions

While ducks are expert navigators, changes in the environment or human activities can disrupt their migration patterns. For instance, light pollution from cities can disorient ducks flying at night, leading them off course. Large-scale deforestation or urbanization can remove the natural landmarks that ducks use to navigate, making it harder for them to find their way. In some cases, ducks may even end up in unsuitable habitats where they cannot find enough food or shelter to survive.

Understanding The Challenges

Migration is a test of endurance, skill, and adaptability for ducks. The challenges they face—from habitat loss and climate change to predation and human-made hazards—highlight the fragility of these incredible journeys. Despite these obstacles, ducks continue to migrate each year, driven by instinct and the promise of favorable conditions in their breeding and wintering grounds. By understanding the challenges they face, we can better support conservation efforts to protect the habitats and resources that ducks rely on, ensuring these remarkable migrations continue for generations to come.

Have you ever wondered how your ducks might fare on such a journey? The challenges they face in the wild make us appreciate the safety and care we can provide for them at home!

Duck Species and Their Migration Patterns

Different species of ducks follow unique migration patterns, with some traveling thousands of miles each year. Their routes, timing, and destinations vary widely depending on the species. Below is a list of common migratory duck species, their typical routes, and the timeframes they travel.

1. Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

- Route: Mallards are found across North America and use all four major flyways—Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific. They breed in Canada and the northern U.S. and winter in the southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

- Migration Pattern: Mallards are versatile and can adjust their migration based on weather and food availability. Some populations may remain in northern areas if conditions are mild.

- Travel Dates: Migration begins as early as September and can extend into December, with the return trip north starting in February or March.

2. Northern Pintail (Anas acuta)

- Route: Northern Pintails primarily use the Pacific, Central, and Mississippi Flyways. They breed in Alaska, Canada, and the northern Great Plains and winter along the southern U.S. coast, Mexico, and Central America.

- Migration Pattern: These ducks are known for their long migrations, often traveling over 2,000 miles. They prefer open wetlands and agricultural fields during migration.

- Travel Dates: Northern Pintails typically begin their migration in late August, with peak movement in October and November. The return migration occurs from February through April.

3. Blue-winged Teal (Spatula discors)

- Route: Blue-winged Teal primarily use the Central and Mississippi Flyways, with some also traveling the Atlantic Flyway. They breed in the northern U.S. and Canada and winter in Central and South America, as far as Argentina.

- Migration Pattern: Among the earliest migrants, Blue-winged Teal are often the first ducks to head south, making an impressive long-distance journey.

- Travel Dates: These ducks start migrating as early as August, with most completing their journey by mid-October. Their northward migration begins in March and April.

4. Green-winged Teal (Anas crecca)

- Route: Green-winged Teal are found across all four flyways. They breed in Alaska, Canada, and the northern U.S., wintering in the southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

- Migration Pattern: These small, fast-flying ducks are adaptable and often stop at a variety of wetland habitats during migration.

- Travel Dates: Migration begins in September and peaks in October and November. They return north starting in March, with most arriving by April.

5. Canvasback (Aythya valisineria)

- Route: Canvasbacks use the Mississippi and Central Flyways, with some also migrating along the Atlantic Flyway. They breed in the northern U.S. and Canada and winter in the southern U.S., primarily along the Gulf Coast.

- Migration Pattern: Known for their preference for large, open water bodies, Canvasbacks often migrate in large flocks.

- Travel Dates: Migration starts in October and November, with the return migration beginning in March and April.

6. Redhead (Aythya americana)

- Route: Redheads follow the Central and Mississippi Flyways. They breed in the prairie pothole region of the U.S. and Canada and winter in the Gulf Coast and Mexico.

- Migration Pattern: Redheads are strong fliers and often migrate in large groups, stopping at key wetland sites along their route.

- Travel Dates: These ducks typically migrate in October and November, with their return trip beginning in February or March.

7. Northern Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

- Route: Northern Shovelers migrate along the Central, Mississippi, and Pacific Flyways. They breed in the northern U.S. and Canada and winter in the southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

- Migration Pattern: These ducks prefer shallow wetlands during migration, where they can use their specialized bills to sift through mud for food.

- Travel Dates: Migration occurs from September to November, with the return north beginning in March.

8. American Wigeon (Mareca americana)

- Route: American Wigeons use the Pacific, Central, and Mississippi Flyways. They breed in the northwestern U.S., Canada, and Alaska and winter along the southern U.S. coast and Mexico.

- Migration Pattern: American Wigeons are often seen in mixed flocks with other dabbling ducks, and they favor wet meadows and marshes during migration.

- Travel Dates: They start migrating in September and October, with the return trip beginning in February and March.

9. Gadwall (Mareca strepera)

- Route: Gadwalls primarily use the Central and Mississippi Flyways. They breed in the northern U.S. and southern Canada and winter in the southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

- Migration Pattern: Gadwalls are known for their preference for large, shallow lakes and wetlands during migration.

- Travel Dates: Migration typically occurs in October and November, with the return north beginning in March and April.

10. Cinnamon Teal (Spatula cyanoptera)

- Route: Cinnamon Teal use the Pacific Flyway, breeding in the western U.S. and Canada and wintering in Central and South America.

- Migration Pattern: These ducks prefer freshwater marshes and are less likely to be seen in large flocks compared to other teal species.

- Travel Dates: Migration starts in late August and peaks in September and October. The return journey begins in March.

Each duck species has its own unique migration pattern, shaped by the need to find suitable breeding and wintering habitats. Their journeys can be incredibly long and challenging, but these ducks are well-adapted to their migratory lifestyles. Understanding these patterns helps us appreciate the diversity of duck species and the importance of conserving the habitats they rely on along their routes. Whether you spot a Mallard in your local park or see flocks of Northern Pintails overhead, you’re witnessing the remarkable phenomenon of duck migration in action.

Observations from Our North Texas Pond

Living in North Texas, we’re fortunate to have a front-row seat to one of nature’s most fascinating spectacles—duck migration. Our pond, nestled behind the house, becomes a bustling hub of activity during winter as several species of ducks make it their seasonal home. It’s a joy to watch them arrive, settle in, and eventually prepare for their journey back north when spring arrives.

Year-Round Residents

- Mallards: These adaptable ducks are with us through all seasons, adding a consistent splash of color and sound to the pond. We often see them dabbling in the shallow waters, foraging for food, or simply floating leisurely across the pond. They’re particularly active in the spring, when they start nesting and raising their ducklings, providing endless entertainment as the young ones learn to swim and forage.

- Wood Ducks: The Wood Ducks are another constant presence at our pond. Their striking plumage and distinctive call make them easy to spot, even as they often prefer the more secluded, wooded edges of the pond. They nest in the trees around the pond and are particularly busy in the spring, guiding their ducklings from the nests to the safety of the water.

Winter Visitors

When the temperatures drop and the days shorten, our pond welcomes several migratory species that make North Texas their winter home.

- American Wigeon: These ducks arrive with cooler weather and stay through winter. They’re known for their distinctive whistle-like calls and their grazing behavior, often seen pulling at aquatic plants or feeding on grassy areas near the water. They bring a cheerful, lively energy to the pond during the colder months.

- Lesser Scaup: These diving ducks are also winter visitors. They’re easily recognized by their bright yellow eyes and blue bills, often seen diving beneath the surface of the pond in search of food. Their arrival marks the beginning of winter, and they stay until the first signs of spring.

- Canada Geese: Although not as frequent as our duck visitors, Canada Geese occasionally make an appearance during the winter. Their loud honks and large size are unmistakable and usually arrive in small flocks. They spend their time grazing on the banks or swimming in the open water, adding a new dynamic to the winter pond.

Seasonal Changes

The changing seasons bring a shift in the pond’s atmosphere. In the winter, the arrival of our migratory visitors creates a bustling scene, with different species mingling and interacting. The year-round residents, Mallards and Wood Ducks seem to enjoy the company, often joining the larger flocks as they forage and rest.

As spring approaches, the winter visitors start to depart, heading back to their breeding grounds further north. The pond quiets down, and our focus returns to the Mallards and Wood Ducks, who begin their nesting season, ensuring the cycle of life at our pond continues.

These seasonal patterns provide us with endless hours of observation and enjoyment and deepen our connection to the natural rhythms that govern the lives of these incredible birds. Whether they’re here for just a few months or all year round, each species plays a vital role in the vibrant ecosystem of our North Texas pond.

How does Duck Migration relate to our Backyard Flock of Domestic Ducks?

Duck migration and your backyard flock of domestic ducks may seem worlds apart, but there are fascinating connections between the two.

Shared Instincts with Wild Ducks:

While backyard ducks don’t migrate, they share many of the same instincts and behaviors as their wild counterparts.

- Seasonal changes that trigger migration in wild ducks also influence domestic ducks.

- As days shorten and temperatures drop, you may notice your ducks:

- Increasing their foraging.

- Fluffing up their feathers for warmth.

Insights into Care Through Migration:

Understanding migration can help inform the care of your backyard ducks.

- Migratory ducks rely on diverse habitats, such as wetlands, for food and shelter.

- To keep your flock thriving, provide:

- Plenty of fresh water.

- Access to foraging opportunities.

- Safe and comfortable shelter.

Living in a Migratory Hotspot:

If you’re in a migratory hotspot like North Texas, your domestic ducks can coexist with visiting wild species.

- A deeper connection to the world of duck migration.

- This creates a unique blend of domestic and wild duck interactions in your backyard.

- Your flock may encounter migratory species, offering:

- Observation opportunities.

In essence, while your domestic ducks aren’t travelers like their wild counterparts, the rhythms of migration still resonate in their behavior and needs, linking your backyard flock to the grander natural cycles that govern duck life across the globe.

A Wonder of Nature

Duck migration is a remarkable journey that connects landscapes, climates, and ecosystems across vast distances. Understanding the intricate patterns and behaviors of migrating ducks gives us insight into the resilience and adaptability of these incredible birds. From the major flyways that guide them to their seasonal destinations to the specific challenges they face along the way, each aspect of migration showcases nature’s extraordinary complexity.

For those of us lucky enough to witness this annual spectacle, whether through observing the flocks passing overhead or welcoming winter visitors to our local ponds, duck migration offers a unique opportunity to connect with the natural world. Our observations in North Texas, where Mallards and Wood Ducks stay year-round while others like the American Wigeon and Lesser Scaup join us in winter, remind us of the delicate balance these birds maintain between survival and their instinctual drive to migrate.

Watching them come and go with the changing seasons reminds us of preserving the habitats supporting these journeys. Whether it’s the wetlands they rely on during migration or the local ponds that provide a safe haven during the colder months, every effort we make to protect these environments contributes to the continued success of their remarkable migrations.

When we observe and understand duck migration, we appreciate the beauty and determination of these birds and recognize our role in ensuring that these ancient patterns continue for generations to come.

Do you have a favorite duck species you’ve noticed during migration? Let’s share the joy of observing these incredible travelers!

What preventative measures can be taken to ensure my ducks stay healthy and avoid common illnesses? Are there any natural remedies or supplements that can boost their immune system and overall well-being?”,

“refusal

There are many vitamin and electrolyte supplements that can help increase your ducks immune system. Read more about this in our article on the first aid kit for ducks.